Age-Related Macular Degeneration Linked to Severe Vascular Disease

Vascular disease limits blood flow to the retina and can lead to one subtype of AMD, researchers say.

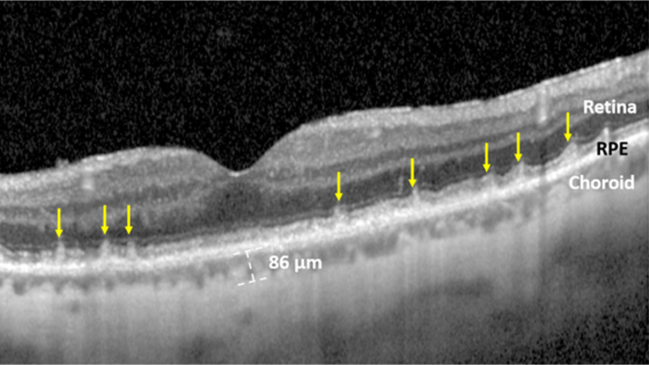

OCT image of SDDs (marked by yellow arrows) in the retina of a patient with prior MI. Photo Credit: Mount Sinai Health System.

Among patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD), those whose eyes have signs of subretinal drusenoid deposits (SDDs) are more likely to have high-risk vascular disease (HRVD) than those who don’t have this feature, a new study has found.

The results are early and must be confirmed, researchers say, but they open a window to the potential for future screening strategies targeted at patients with AMD (to check for cardiovascular disease) and at patients with known CVD (to check for eye disease).

“I’d been noticing for maybe as much as 10 years that there seemed to be some kind of connection—that people have these abnormal deposits in their retina and vascular disease,” said senior author Roland Theodore Smith, MD, PhD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY). Yet earlier research on AMD as a whole and its connection to CVD hadn’t shown consistent results, he explained.

The two main types of deposits seen within the retinas of people with age-related macular degeneration are SDDs and drusen. As it turns out, Smith continued, only SDDs appear to show this link. “The mechanism is quite clear,” he added, in that SDDs appear to develop due to limited oxygen, thanks to low blood flow, and are seen in conjunction with vascular disease that’s severe enough to be responsible for limiting perfusion.

Nell Gregori, MD (Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, FL), a clinical spokesperson for the American Academy of Ophthalmology, said the study shows a “very interesting correlation” between this anatomical feature of AMD and the presence of systemic cardiovascular disease, with a potential mechanism.

“While it is not enough to recommend universal screening for SDDs (reticular pseudodrusen), the ophthalmologists should be aware of these newly discovered correlations and keep an eye out for possible future screening recommendations,” Gregori told TCTMD in an email. “On the other hand, the cardiologists and neurologists should recommend their patients with HRVD to have an annual eye exam with ophthalmologists to screen for possible AMD and other silent eye conditions.”

The study, with Gerardo Ledesma-Gil, MD (Institute of Ophthalmology Fundación Conde de Valenciana, Mexico City), as lead author, was published online November 17, 2022, in BMJ Open Ophthalmology.

Valve Disease, Myocardial Damage, and Stroke/TIA

For the study, Ledesma-Gil and colleagues enrolled 200 people with AMD (mean age around 79 years; 61% women). Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging showed that 97 had SDDs (with or without drusen) and 103 had only drusen.

The presence of HRVD—defined as cardiac valve defect, myocardial defect, and stroke/TIA—was ascertained using health history questionnaires. In all 47 people reported HRVD: 19 with heart failure or MI, 17 with serious valve disease, and 11 with stroke originating in the carotid artery. Of those 47, 86% had SDDs. Of the 153 who did not report HRVD, 43% had SDDs.

Looking from the opposite direction, fully 41.2% of those with SDDs had some form of HRVD, as opposed to just 6.8% of those whose eyes only had drusen (OR 9.62; 95% 4.04-22.91).

On multivariate analysis, only the presence of SDDs and low HDL levels (in the lower two quartiles) significantly predicted HRVD risk. A model that assumed a patient with both SDDs and an HDL level below 61 mg/dL would have HRVD (but not have HRVD if they didn’t meet these criteria) achieved a specificity of 83.0%, sensitivity of 63.8%, and accuracy of 78.5%.

Smith acknowledged to TCTMD that some ophthalmologists might find his proposed mechanism for the relationship between hypoperfusion and the development of SDDs unconvincing. As a counterpoint, he described scenarios he’s seen where a patient has a stenosis in one internal carotid artery but not the other, and SDDs can be detected ipsilaterally on the affected side.

Next steps for research ideally should come from the cardiovascular side, enrolling patients with varying levels of disease severity and imaging their retinas with OCT, he suggested.

Smith said that before the current findings can be applied in the real world, they must be validated in a large multicenter study, one that includes analyses related to gender, age, and race/ethnicity. “Then general recommendations could be considered by the American Heart Association and American Academy of Ophthalmology. However, at the present time, what we think makes sense is that any middle-aged or older person with any vascular risk factors—[high] blood pressure, cholesterol—or any person with unreported or undiagnosed symptoms of heart failure, heart disease, or TIA should get retinal imaging and take a look,” he said.

If OCT reveals SDDs or choroidal thinning, then it makes sense to get evaluated for cardiovascular disease, Smith suggested, adding that this is particularly true for people with low HDL levels.

“That’s what I would recommend to my patients now,” he said.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Ledesma-Gil G, Otero-Marquez O, Alauddin S, et al. Subretinal drusenoid deposits are strongly associated with coexistent high-risk vascular diseases. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2022;7:e001154.

Disclosures

- This study was funded by a Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Investigator-Initiated Study, Research to Prevent Blindness Challenge Grant, the Macula Foundation, a Bayer-Global Ophthalmology Award, and the International Council of Ophthalmology-Alcon Fellowship.

- Ledesma-Gil reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Smith reports serving as a consultant to Ora Technologies.

Comments