Bariatric Surgery: Cardiometabolic Benefits Down, but Not Out, at 5 Years

Overall, just 23% of obese patients treated surgically hit all three targets of sufficiently controlled HbA1c, LDL-C, and systolic BP, say investigators.

Nearly one-quarter of obese individuals with poorly controlled diabetes who undergo gastric bypass surgery continue to have adequate control of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels at 5 years, as well as good control of LDL cholesterol and systolic blood pressure, according to extended follow-up of the Diabetes Surgery Study.

While the benefits of gastric bypass surgery for the treatment of obesity and diabetes are still evident long term, the effects of bariatric surgery on various cardiometabolic risk markers diminish over time, report investigators.

“At 5 years, there is still a statistically significant benefit in gastric bypass surgery, but now the size of that benefit isn’t nearly as large as it was at 1 year,” senior investigator Charles Billington, MD (University of Minnesota, Minneapolis), told TCTMD. “We were very enthused about the gastric bypass effect at year one and we were, of course, hoping it would hold up, but it really didn’t, I would say.”

The long-term results, which were published January 16, 2018, in a special issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association devoted to obesity and weight-loss surgery, suggest further follow-up is needed to fully understand the durability of gastric bypass surgery.

Carel le Roux, MD, PhD (University College Dublin, Ireland), who was not involved in the trial but who has studied the impact of bariatric surgery on diabetes, said that when the Diabetes Surgery Study was designed, the thinking was that weight-loss surgery could put diabetes into remission and even cure it to the point where medication would not be necessary. That is no longer the thinking, he said.

“What we’re seeing is the natural history of the disease,” said le Roux. “Surgery can put diabetes into remission for a while, but then what we’re seeing is an inevitable creeping up of lipids, blood pressure, and glycemia. What this really tells us is that it’s not surgery failing—surgery is controlling the disease—but on its own it’s not enough. We need to use surgery and combine it with statins, with ACE inhibitors, with metformin, and with other drugs. If we do that, we can put the disease into remission and keep it there longer.”

Small Study, Important Findings

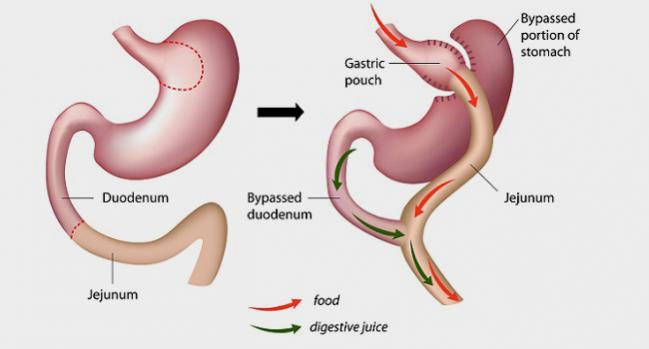

The Diabetes Surgery Study initially randomized 120 patients with HbA1c levels of 8.0% or higher and a body mass index between 30.0 and 39.9 to lifestyle management and medical therapy with or without the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients who achieved the American Diabetes Association (ADA)’s triple endpoint of HbA1c less than 7.0%, LDL cholesterol less than 100 mg/dL, and systolic blood pressure less than 130 mm Hg.

After 1 year, 50% of patients randomized to gastric bypass surgery achieved the composite triple endpoint compared with 16% in the lifestyle/medical management arm (P = 0.003). By 5 years, however, just 23% of participants treated with surgery and 4% treated with lifestyle/medical management achieved the ADA’s triple endpoint (P = 0.01). The percentage of patients who achieved the triple endpoint declined in both arms from year one to year three and remained relatively stable to year five, report investigators.

Regarding individual components of the primary endpoint at 5 years, 55% achieved an HbA1c level of less than 7% compared with 14% in the lifestyle/medical management arm (P = 0.002). Control of systolic blood pressure to less than 130 mm Hg was 73% in the surgery arm versus 49% in the lifestyle/medical therapy group (P = 0.06). Finally, 77% of the surgery patients achieved the LDL target compared with 47% of those managed with lifestyle/medical therapy alone (P = 0.02). Like the primary composite endpoint, control of the individual risk markers declined over time.

At 5 years, weight loss in the surgery arm was larger than in those managed medically. To TCTMD, Billington noted that patients treated with surgery had lost, on average, 21.8% of their baseline body weight at 5 years. Researchers had initially worried weight gain over time would degrade the benefits of surgery and result in the “creeping up” of HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and systolic blood pressure.

“It looks like weight is not the issue,” said Billington.

He pointed out they had funding for the intensive lifestyle/medical management aspect of the study—which both groups received—for only 2 years. In addition to no longer having access to lifestyle and behavior counseling, patients lost access to the study medications. When they returned to usual care beyond year two, some patients had trouble accessing these medications, such as glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, from their insurance providers.

Billington also highlighted baseline pancreatic function as a potential reason for the lack of surgical durability.

“One of the questions we also have is how good the beta cell function is for these patients before they had the surgery,” said Billington. “We think this might be an important factor. If the beta cells are too far gone, if you do weight-loss surgery, you’re still not going to get a lasting benefit. That’s a theory that now needs to be tested.”

Still Resistance to Bariatric Surgery

In the study, the rate of complete diabetes remission at 2 and 5 years—defined as HbA1c levels 6.0% or less at consecutive annual visits without use of antihyperglycemic medications—was just 16% and 7% in the gastric bypass group, respectively.

Those who underwent gastric bypass were taking 2.0 medications, on average, at 5 years compared with 4.4 medications taken by those in the lifestyle/medical management arm. “We do see a benefit here with gastric bypass,” said Billington. “The number of people who are completely off medication, there’s not many of those, but they’re taking fewer drugs. For some people, that would be considered a benefit.”

Le Roux noted there remains a societal resistance to bariatric surgery, although it depends on how the procedure is framed. If it’s framed as a treatment for obesity, there is a lot of pushback, “mainly because people don’t recognize obesity as a disease” but rather as a self-inflicted condition, he said.

He believes surgery should be framed as treatment for diabetes, one that is also going to require supplemental medication to hold the disease at bay. A large number of studies, including the present one, have shown the positive effects gastric bypass surgery can have on diabetes, as well as other risk factors, irrespective of the weight scale, he said.

Benefits Corroborated, Potential Risks Highlighted

Other analyses are also featured in this week’s JAMA, including a retrospective cohort study suggesting surgery can add years to patients’ lives. After a median follow-up of 4.5 years, all-cause mortality in more than 8,000 patients was two times higher among those treated with medical management than in those treated with surgery. Additional data from Norway corroborated the diminished long-term findings from the Diabetes Surgery Study, with investigators observing similar rates of diabetes and hypertension remission in 1,888 patients treated at a single tertiary-care center.

The Norwegian analysis, however, also highlighted some potential risks of the procedure. For example, Gunn Signe Jakobsen, MD (Vestfold Hospital Trust, Tønsberg, Norway), reported higher rates of depression, opioid use, and the need for gastrointestinal surgery among those who underwent bariatric surgery. The researchers say these risks are “clinically important” and should be considered in the decision-making process.

Similarly, a study published January 9, 2018, in Lancet: Diabetes and Endocrinology, also raises concern about potential risks associated with bariatric surgery. Analyses of the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) study and Scandinavian Obesity Surgery registry showed that patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery had a higher rate of suicide and self-harm compared with obese patients treated with intensive lifestyle management.

The researchers stress, however, that event numbers were small and the absolute risks low, meaning they do not justify a “general discouragement of bariatric surgery.” Instead, the findings “indicate a need for thorough preoperative psychiatric” history as well as continued monitoring of mental health after the procedure, they suggest.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Ikramuddin S, Korner J, Lee W-J, et al. Lifestyle intervention and medical management with and without Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and control of hemoglobin A1c, LDL cholesterol, and systolic blood pressure at 5 years in the Diabetes Surgery Study. JAMA. 2018;319:266-278.

Jackobsen GS, Småstuen MC, Sandbu R, et al. Association of bariatric surgery vs medical obesity treatment with long-term medical complications and obesity-related comorbidities. JAMA. 2018;319:291-301.

Reges O, Greenland P, Dicker D, et al. Association of bariatric surgery using laparoscopic banding, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, or laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs usual care obesity management with all-cause mortality. JAMA. 2018;319:279-290.

Neovius M, Bruze G, Jacobson P, et al. Risk of suicide and nonfatal self-harm after bariatric surgery: results from two matched cohort studies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Billington reports receiving institutional grant support from Medtronic, the National Institutes of Health, and the Department of Veterans Affairs, and consulting for Novo Nordisk, Enteromedics, and Optum.

Comments