Cardiogenic Shock: Protocols, Clear Definitions Advance the Field

Final NCSI data make the case for standardized care, while the SCAI shock categories create a common language for clinicians.

Two new studies document the progress that’s been made in creating a consistent approach to cardiogenic shock care, and point to new directions as the field evolves. Both were released this week in a late-breaking session of the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) 2021 virtual meeting.

Jacob Jentzer, MD (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), presented pooled data confirming that SCAI’s classification system for shock severity tracks closely with mortality risk. Babar Basir, DO (Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI), shared final results from the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative (NCSI) showing that an algorithm emphasizing early use of mechanical circulatory support can offer better survival for patients with acute MI complicated by cardiogenic shock (AMICS).

Altogether, these reports exemplify how “there are a lot of observational data now that suggest we may be seeing a paradigm shift in shock from diagnosis to risk stratification and then ultimately management,” Behnam N. Tehrani, MD (Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, VA), commented to TCTMD. Tehrani’s own work has called for a multidisciplinary, “agnostic” approach.

The SCAI shock definitions, for example, “can help to stratify this very sick patient population in a way that previous mechanisms were unable to. It incorporates three cross-disciplinary domains—the physical exam, laboratory markers, and hemodynamics—and it creates a common language” for communications among intensivists, cardiologists, heart failure specialists, and cardiac surgeons, said Tehrani, noting that it also “creates goalposts to emphasize how time-sensitive the condition is.”

And the NCSI, with its clearly outlined algorithm, “proves that protocol-based care works,” he told TCTMD. “NCSI demonstrates that the patients derive the greatest benefit when team members are working in concert, using standardized protocols.”

This is welcome news. Cardiogenic shock, with its rapid changes and high stakes, has proven hard to study, as reported by TCTMD. There’s hope that the ongoing DanGer trial and other upcoming RCTs will provide clarity.

SCAI Shock Stages

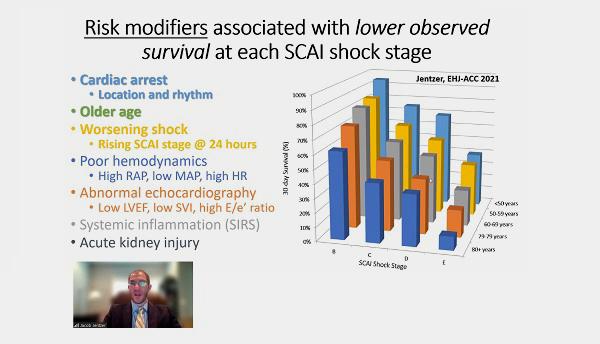

In 2019, SCAI released the first-ever standardized set of definitions for cardiogenic shock. “We wanted to see if this was actually able to predict mortality in real-world situations,” Jentzer said, noting that the study he presented emerged as part of a SCAI-sponsored consensus update to that document.

Jentzer et al identified 14 published papers in the literature with more than 15,000 patients who presented with cardiogenic shock, had out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, or were admitted to a cardiac intensive care unit. Most of the studies were retrospective, but one “prospectively assigned SCAI shock stage,” he said.

Each study individually showed a stepwise increase in-hospital/30-day mortality across SCAI shock stage, said Jentzer. “Observed mortality is greater at each higher shock stage and varies substantially according to the study definition, population, and concomitant risk factors.”

Death Risk by Shock Stage in Combined 14-Study Data

|

|

Mortality |

|

A (At-risk): Patients are hemodynamically stable but have acute CVD that puts them at risk for cardiogenic shock. |

1-5% |

|

B (“Beginning”): Patients are starting to show signs of hemodynamic instability, including hypotension/tachycardia, but do not have cardiogenic shock. |

0-34% |

|

C (“Classic”): Patients have cardiogenic shock characterized by hypoperfusion without deterioration. |

11-54% |

|

D (“Deteriorating”): Patients have cardiogenic shock and hemodynamic instability and/or hypoperfusion that does not respond to initial interventions. |

24-68% |

|

E (“Extremis”): Patients have cardiogenic shock, are being supported by multiple interventions, and may be experiencing cardiac arrest with ongoing CPR and/or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. |

44-77% |

No matter the shock severity, lower survival was seen in patients with cardiac arrest, older age, worsening shock, poor hemodynamics, abnormal echocardiography, systemic inflammation, and acute kidney injury.

“These data should inform further modifications of the SCAI shock classification,” which will be presented this October at the SCAI Shock meeting, Jentzer concluded.

Discussant Bonnie Weiner, MD, past president of SCAI, agreed that the definitions help “tease out the fact that one size does not fit all” when it comes to shock.

The question, she continued, is “what does this mean in terms of how we treat patients? Yes, we can predict who’s at higher risk for mortality, but . . . can we start to look at whether there are interventions at different stages of shock that might in fact change the outcomes? Clearly the Es are problematic no matter what you do; they may be far enough down the line that there isn’t as much that will benefit [them]. But certainly some of these earlier stages might have some ability to be influenced.”

Jentzer said that the answer to this question has two components. “The first is when we’re working with spoke-and-hub systems of care, we can help our spoke centers use the SCAI stages to identify patients that need to be referred to the hub. And in that way, it’s actually some of the systems of care that may be at least as important, or more important, than the individual therapies,” he explained. Another aspect is that when interpreting prior trials, it’s useful to know whether the intensity of therapy matched the types of patients being treated. Ideally, said Jentzer, future studies will define SCAI stage at the outset.

Speaking with TCTMD, Tehrani said the “NCSI strategy works very well at level 1 shock centers that have expertise with large-bore access and the ability to provide full-spectrum care, with escalation and weaning strategies.” At the community level, it’s also works well, he continued, in that it’s a “blueprint for physicians and other healthcare providers who may not have access to Impella, [so they can] recognize the disease and shift the patients to the level 1 center where they can receive the follow-on care.”

NCSI: Final Results

For the prospective NCSI study, researchers screened 1,103 potential participants, of which 697 were excluded. The most common reasons for exclusion were lack of PCI performed, intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) use prior to Impella (Abiomed) support, and unwitnessed arrest or return of spontaneous circulation > 30 minutes.

“The NCSI included 80 sites in total. Forty-eight of the 80 were large community-based programs, so these are centers where cardiogenic shock patients originally present. It is not just academic centers,” Basir stressed.

Ultimately, they enrolled 406 patients with AMICS at 73 sites between July 2016 and December 2020. Participants’ mean age was 64, one-quarter were female, and two-thirds were admitted in shock.

With the NCSI algorithm—which includes early use of the Impella percutaneous left ventricular assist device, revascularization by PCI, and use of right heart monitoring to rapidly reduce the use of inotropes—99% of patients in stage C/D shock survived their procedures, 79% survived until hospital discharge, 77% were alive at 30 days, and 62% were alive at 1 year. One-quarter of NCSI participants were in stage E shock, the sickest SCAI category. For them, survival rates were 98%, 54%, 49%, and 31%, respectively.

These rates are better than what’s been seen in prior studies of cardiogenic shock, Basir pointed out. This was despite the fact that “when you compare to other studies that have been done, I can definitely argue that this is one of the sickest cohorts ever studied. Blood pressure on average was 77 over 50, 77% of patients had a lactate greater than 2, and the mean lactate was 4.8.” Survival for IABP-treated patients in the 2012 IABP-SHOCK II trial, for example, was just 60% at 30 days and 42% at 1 year.

“When we look at the last 20 years of cardiogenic shock research, we can see that the NCSI represents really the culmination of 20 years of data, improvements in technology, improvements in our understanding of the importance of invasive hemodynamics to guide therapy, and a stepwise increase in overall survival,” he commented. “This is the first push to really be able to consistently get survival rates over 50%, particularly in those patients who presented in stage C and D shock,” said Basir.

However, 1-year mortality remains a problem, he added, emphasizing the need to optimize medical therapy and consider early advanced heart failure follow-up, as well as to explore novel therapies like supersaturated oxygen to reduce infarct size. The latter will be tested in the ISO-SHOCK trial, slated to begin this year. Also planned to begin in 2021 is the RECOVER IV trial, which will evaluate whether Impella support before PCI outperforms PCI done without Impella.

Ron Waksman, MD (MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC), the study’s discussant, said what’s missing is a concurrent control group of non-NCSI hospitals, something that’s impossible to do retroactively. “If we would have opened that to any treatment at the time of the initiative [and] not just limit it to the use of Impella devices, we would have a better understanding if there was really a difference between one of the devices versus the other device,” he observed, also asking if there were outcome differences between the NCSI community hospitals and academic medical centers.

“I think that that’s a very reasonable comment,” Basir said regarding the control group. As to the latter point, he said the participating community hospitals were large and tended to have the same access to technologies as academic centers.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Jentzer J. SCAI shock classification for mortality risk stratification: survey of published evidence. Presented at: SCAI 2021. April 28, 2021.

Basir B. Final results from the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative. Presented at: SCAI 2021. April 28, 2021.

Disclosures

- NCSI is in part funded by unrestricted research grants from Abiomed and Chiesi. Neither company had direct involvement in the study design nor the present analysis.

- Basir reports serving as a consultant to Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, Cardiovascular Systems, Chiesi, Procyrion, and Zoll.

- Jentzer reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Tehrani reports being a consultant to Medtronic and a member of the advisory board for Abbott.

Comments