Conversations in Cardiology: What Has ‘Kept a Fire in the Belly’ for You?

Morton Kern, MD, often engages his colleagues via email in brief, informal dialogue on clinically relevant topics in cardiology.

Morton Kern, MD, of VA Long Beach Healthcare System and University of California, Irvine, often engages his colleagues via email in brief, informal dialogue on clinically relevant topics in interventional cardiology. With permission from the participants, TCTMD presents their conversations for the benefit of the cardiology community. Your feedback is welcome—feel free to comment at the bottom of the page.

Morton Kern, MD, of VA Long Beach Healthcare System and University of California, Irvine, often engages his colleagues via email in brief, informal dialogue on clinically relevant topics in interventional cardiology. With permission from the participants, TCTMD presents their conversations for the benefit of the cardiology community. Your feedback is welcome—feel free to comment at the bottom of the page.

J. Jeffrey Marshall, MD (Northside Hospital Cardiovascular Institute, Lawrenceville, GA), asks:

Our recent discussion on senior transitions was educational for those of us just behind the current cohort who are about to enjoy the fruits of their lifelong careers.

This brought to mind another group of cardiologists who are seeing changes in their careers: the young and mid-career cardiologists.

With the “industrialization” of cardiology (now ~90% of all of us are simply employees), I think we have all seen, in every corner of cardiology, that young and mid-career cardiologists are losing their zeal for this great profession. Some joke that they have been forced to be button sewers on the RVU assembly line, driven by Machiavellian hospital administrators, and that they see “no future” in medicine.

While I do not feel that way, many younger cardiologists feel this “moral injury” or “burnout” from many issues, one of which is the loss of autonomy in the “Industry of Cardiology.”

The question: “What is/was it during your career in cardiology that kept you motivated, that generated the fire in the belly to do your best each day and love being a cardiologist?” I think our younger colleagues, as they face the uphill seasons of their careers in the world of medicine that has transformed so quickly into what they perceive as a grind, need to hear some sage advice and guidance about what ignited and sustained your career and kept you passionate about cardiology.

Kern:

My short answer is that being part of an inaugural PCI generation kept the fires burning in me since new innovation was all around us—and still is. Every month, every year, something new has come into practice. This, coupled with my personal desire to test the truths of our suppositions regarding causes/effects of stenting, lesion function, and ACS, kept me going. It is only this year that I've cut back to 50%. The fire/passion for a career has to come from one's personal priorities, curiosity, and desire to be a contributor through teaching, research, device development, policy implementation, etc, to a bigger effort. There are many opportunities for stimulation that can make a dull day brighter.

Let's see what the top three factors are for my colleagues, both younger and those in my peer group, that keeps them so passionate.

My appreciation for indulging us on this one.

Bonnie Weiner, MD (Saint Vincent Hospital, Worcester, MA):

Jeff, this is a great question. I would suggest, though, that the answer starts well before cardiology, let alone interventional cardiology (which for some of us didn’t even exist when we started). I would suggest that the answer starts with remembering why we went to medical school in the first place. At the risk of sounding “preachy,” it wasn’t a career choice per se. Rather it was a vision of what I wanted to do with my life. It never dawned on me to do anything else. Medical school was the means to the end of doing something challenging, intellectually interesting but having a meaningful impact on people. Medicine and cardiology training fulfilled that vision.

It was all about the patient. Long hours, tough rotations, low pay never were factors. It was all about being responsible for getting the best results and even owning things that didn’t go so well. Seeing more patients, doing more “things” made every day an opportunity for growth. That is not necessarily what our younger colleagues are trained to expect. Duty hours and patient caps do nothing to foster a sense of ownership for the doctor-patient relationship. Every day was interesting. I never knew what it would bring. Yes, there were days when scut work dominated, but still that impacted patient outcomes. Interventional cardiology amped this up even further. Yes, I am part of the generation that saw and participated in the development of the field. Every day was a new opportunity to learn how to do something that made a difference or think about how to do things better, face new challenges, and find solutions.

Bottom line I guess is that keeping the focus on the patient is what kept (and keeps) the fire in the belly. Knowing that patients don’t “read the textbooks” so one size fits all will never work, although “best practices” have value. No matter that medicine in general has become institutionalized and algorithm driven, thinking is not illegal and there is no time clock to punch. The patients depend on us to keep their best interests in mind, not the practice, hospital, system’s bottom line, or even our own. That is what makes us doctors and not just “practitioners” and cardiology a profession, not a career or job.

I will now get off my soapbox.

Ian J. Sarembock, MB, ChB, MD:

“It’s the patients, stupid!!”

Despite the “industrialization” of medicine and all the other challenges and annoyances, focusing on the joy (and privilege) of providing cardiovascular patient care has been my North Star for 35 years as a practicing interventional cardiologist. The advances have been astounding, and coming home every day and being able to say that one has helped one or many patients that day is a true blessing.

BTW - now happily retired . . .

Lloyd W. Klein, MD (University of California, San Francisco):

1. The patients

2. The intellectual challenges

3. The patients

4. The physical and mechanical challenges

5. The patients

6. Being part of a pioneering, innovative field

7. The patients

Paul S. Teirstein, MD (Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, CA):

For me, it’s pretty simple. At the end of each day I want to be sure I have accomplished something worthwhile.

Christopher J. White, MD (Ochsner Health System, New Orleans, LA):

When I read Daniel Pink’s book Drive, it kind of crystalized for me: autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

Michael A. Kutcher, MD (Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC):

I realize we all have different personal and spiritual backgrounds, so it is not my intent to preach. But I found the Prayer of Saint Francis was a great way to start my day and to keep me focused.

The first sentence is: "Lord, make me an instrument of Your peace." And then it goes on with several other inspiring thoughts.

I am a second-generation American of Slovak coal miner immigrants. This prayer reminded me of the sacrifices my grandparents and parents made to give me love, safety, stability, and education. Foremost was the opportunity to be an interventional cardiologist and to have the talent to ease pain and suffering and prolong the lives of my fellow humans.

These are elements that "kept the fire in my belly" during my cardiology career.

Barry Uretsky, MD (UAMS Medical Center, Little Rock, AR):

One of my mentors, Joe Babb, epitomized what keeps me excited about my work: finding joy in service.

James Blankenship, MD (University of New Mexico, Albuquerque):

It is hard to find any better persons to answer that question than Drs. Uretsky and Babb naming it “joy in service.”

Where else can one have such an impact on a life? Today a lady came to our ED with an hour of pain. Screaming and moaning and crying. We popped open the LAD and just like that the pain went away and she was happy. I’ve had patients who came in to the lab like that ask me on the way out, “Can I go home today?” You have all had that experience. What a blessing to be able to do that for a person. And how can we not strive to be at our absolute best so we can provide the best possible service to our patients?

Srihari S. Naidu, MD (Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY):

Great question. For me, it’s the stuff that has lasting memory to me personally. First and foremost, it’s the patients that I’ve taken care of now over almost two decades. That longitudinal care and relationship-building has been fun and rewarding on a truly personal level. I’ve seen my patients at the Knicks games, visited their homes to share their vintage car collection, and even stayed at the bed and breakfast of one of my patients annually with my son, to name some examples. This is the fun part of doctoring, getting to be part of someone’s family over time and helping them get through their most trying times. I think it’s why we went into medicine, and it remains truly unique and sacred.

I do believe also that autonomy plays a big role in keeping that fire in the belly going, and that the lack of it leads to burnout. I’ve been able to manage some degree of autonomy by building programs that allow me to have my own team within the larger department, where I can create a culture of belonging, purpose, and quality that my patients (and team) deserve. This allows us to be proud of what we’ve created, without being constantly hassled, which goes a long way in feeling fulfilled and valued.

Above and beyond this, I feel interventional cardiology allows us to be creative, fostering ideas that can materialize into concepts, publications, or movements. For me, that’s been the whole concept of interventional heart failure leading to cardiogenic shock, and the field of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in general. It’s wonderful to feel part of something larger like that, meet other like-minded experts, and work together in the professional societies with their grand missions. Being part of something much bigger than any individual goes a long way to feeling fulfilled and maintaining drive.

Further, for all of us who simply love using our hands, our field constantly evolves and allows us to grow and offer more and more to our patients.

And finally, the mentoring. Seeing our residents and fellows become amazing doctors, and seeing those who look to us for mentorship grow into their potential and accomplishments is something that I cherish. I absolutely love seeing my mentees or colleagues do amazing things, and knowing that I was even a small part of that brings me a lot of joy and pride. I look up to my mentors so much, and being able to pay that forward has a lot of meaning to me.

I do fear that the way healthcare is right now some of these things that have kept us going are facing new challenges. The ownership of patients in particular is a tough one to continue in this day of patient handoffs and reliance on technology over talking to and examining your patients. The limited time per patient visit is a real problem, as well. And not everyone affords themselves of the opportunities in professional societies for networking and being part of something bigger, mainly because the challenges of day-to-day RVU counting limits time away from work and that time should rightly also be spent with family or loved ones. And of course hospitals and insurance companies have increasingly boiled us down to anonymous providers, while the Sunshine Act has placed a wedge between physicians and innovation. Finding a way to navigate these challenges is going to be hard for those who come after us, but hopefully these discussions will help. If there’s one thing we all know, if there’s a will, there’s a way. Let’s help them find it. Thanks for the opportunity to comment.

Samuel Butman, MD (Heart & Vascular Center of Northern Arizona, Cottonwood):

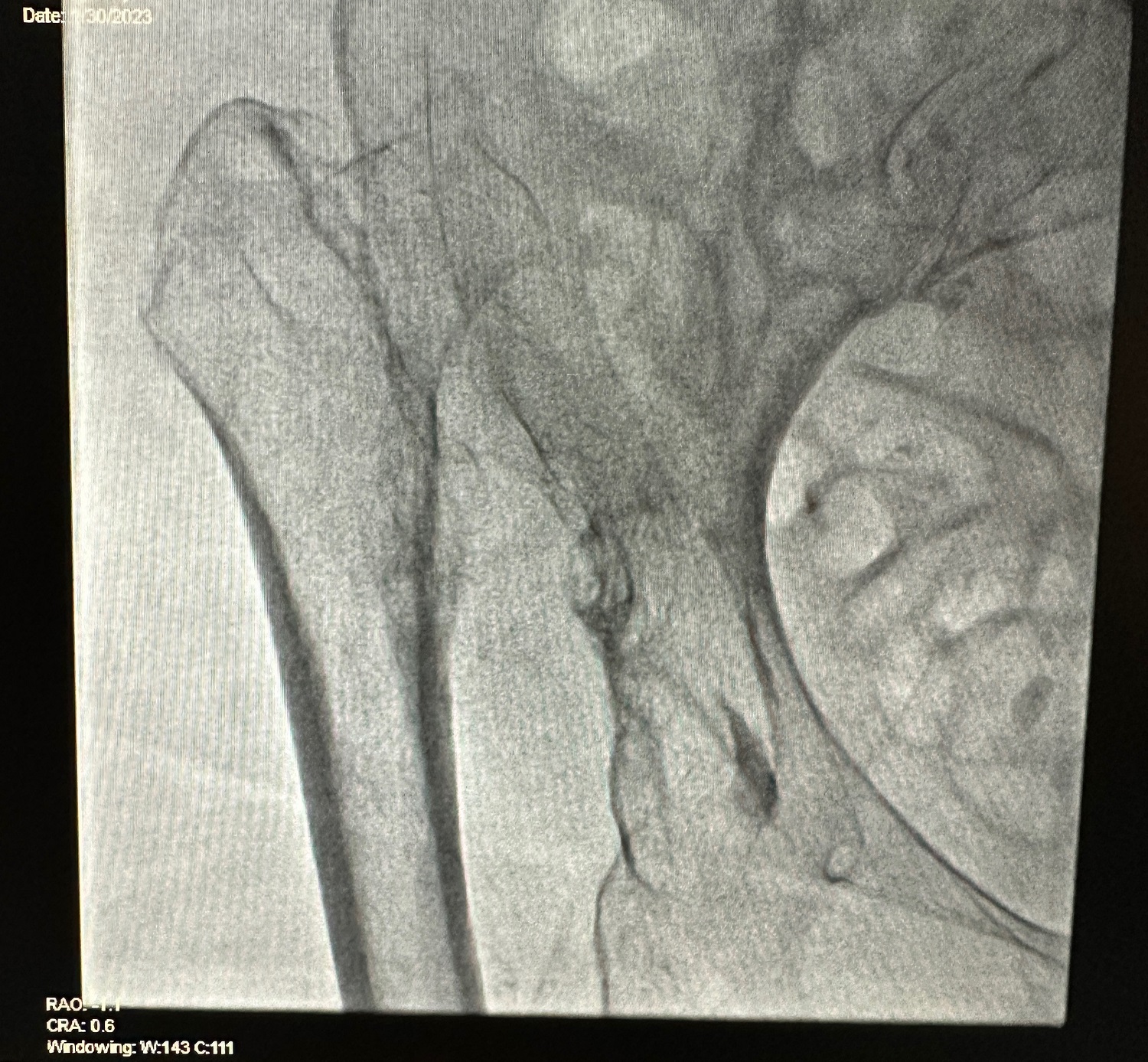

I have been thinking about the question, why do I do what I do, while doing locums in northern Iowa this past weekend. At 10-15 degrees below zero and way too much snow, and with quite a few patients to round on and several interventional cases, I only had time to read the comments of others until last night. But last night, it came to me in the form of a vision, actually a picture and a patient. Forgive me as it will take a moment to explain. It was an intervention I had to do on a sweet 91-year-old lady who initially did not wish any intervention during or in the days after her acute anterior-wall STEMI, but because of recurrent chest pain and nausea despite meds, she asked me to do the “thing.”

First step, keep it simple and fluoro the groin for a proper stick. I did lean over and ask if she walked regularly until this admission. She did.

Anyway, all went well regarding the 99% proximal high-grade, severely calcified LAD.

This picture sums up why I and many of you have always enjoyed the practice of cardiology, be it bedside, clinic, or interventional. It is always interesting! It is often unique even after 40-plus years! No two days are alike. Ever! Yes, sometimes the work seems burdensome, like when an acute inferior-wall MI comes in while I was trying to manipulate a wire through the TIMI 2 proximal LAD calcified lesion—yes, in that same case, LOL—and yes, despite all being long in years, we all did fine.

This picture sums up why I and many of you have always enjoyed the practice of cardiology, be it bedside, clinic, or interventional. It is always interesting! It is often unique even after 40-plus years! No two days are alike. Ever! Yes, sometimes the work seems burdensome, like when an acute inferior-wall MI comes in while I was trying to manipulate a wire through the TIMI 2 proximal LAD calcified lesion—yes, in that same case, LOL—and yes, despite all being long in years, we all did fine.

It is not about the money. It has never been about the money for me and clearly not for those who have already opined. Most of us could have made much more for sure. But to use some of the words other have used, it’s about “curiosity,” “intellectual challenges,” and the fun of meeting a never-ending number of interesting people and their problems.

The answer to the pelvic picture is available by directing an email to me, or if you are a good Googler look it up or maybe show the photo to an orthopedic surgical friend. I did the former. If you already knew, good for you! I’m sure you were as taken aback as I was!

Augusto Pichard, MD (Abbott, Washington, DC):

I echo what several of you have expressed: the fascination of being in a specialty that was exploding with new options to better treat patients with heart disease, and knowing we were providing good solutions to each patient. And we did this in collaboration with colleagues from all over the world!.

Also, building a team of experts and always working closely with them was an important driver for me.

Finally and also important for me, was the opportunity to teach the young generations and seeing them flourish in their own terms.

I feel very fortunate I could do most of it without the current burdens of "paper/administrative" work.

BTW, I am retired from clinical practice, and grateful life has given me the opportunity for this fascinating new chapter!

Jonathan Tobis, MD (UCLA Health, Los Angeles, CA):

For those of us who started our careers before there was any such thing as interventional cardiology, the "fire in the belly" was always there. It was so exciting to be able to help people in such a meaningful way. When we started, the cardiologist just made the diagnosis and then handed the patient off to the surgeon, who stood on the pedestal because he could "fix the patient" with open heart surgery. Then things began to change and there is now a much more equal relationship between the cardiac surgeon and interventional cardiologist.

My patients who were appreciative of what "that masked man" did, did not realize that I was just as appreciative of them for trusting in me. What excitement, what an adrenaline rush to perform angioplasty and all the other interventional procedures that followed.

Another aspect that kept my enthusiasm going was the fascinating research and the exposure to the world's other cardiologists. I was involved in the initial development of digital angiography and gave the highlighted lecture at an AHA meeting in the mid-1980s of the first digital cases ever performed in the cath lab. Then I was on a team that helped develop one of the first intravascular ultrasound devices. This helped to explain the mechanism of coronary angioplasty, rotational atherectomy, lasers, directional atherectomy, and ultimately, in association with Antonio Colombo in Milan, our understanding of how to improve coronary artery stenting. It was so exciting to work in another country with someone as creative and generous as Antonio. And now, for the past 20 years I have been involved in fascinating research with patent foramen ovale. Although we knew that PFOs were present in some people, it took years to understand its association with stroke, migraine, decompression illness, and altitude sickness . . . and now maybe with coronary spasm.

So the research in this incredible field also stoked the fire, and still does at age 75.

The Bottom Line From Mort Kern

Passion for our profession has driven us over these many years. I believe sharing our history, anecdotes, and experiences with our colleagues and particularly our younger generation of interventionalists is a privilege and a duty. The oral and written history of cardiology and PCI has important life lessons and career guideposts that I hope will be useful as they continue their journey to move the field forward.

Conversations in Cardiology reflect the opinions of the individuals invited to participate in these discussions and not those of TCTMD.

Comments