CvLPRIT: Long-term Reduction in Death/MI With Complete Revascularization

The new data confirm the results observed in COMPLETE and may warrant an upgrade of the clinical guidelines, say experts.

Long-term follow-up of the CvLPRIT trial shows that the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events continues to favor STEMI patients with obstructive multivessel disease who underwent complete revascularization compared with patients who had PCI of the culprit lesion only.

Complete revascularization also was associated with a lower risk death and MI, with investigators reporting that after a median follow-up of 5.6 years, 10.0% of STEMI patients who underwent complete revascularization died or had an MI compared with 18.5% of patients randomized to PCI of the infarct-related artery alone (P < 0.0175).

The results, published online before print December 16, 2019, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, are encouraging in that treating the non-infarct-related artery at the time of the index admission didn’t lead to any trouble down the road.

“You might suspect that there could be catchup with these patients,” lead investigator Anthony Gershlick, MBBS (University of Leicester, England), told TCTMD. “If you’re going to intervene in a non-infarct-related artery, because revascularization is more likely to happen in a stented artery than in a nonstented artery, you might think revascularization in the non-infarct-related artery would attenuate the benefits. In fact, the need for ischemia-driven revascularization was very low in all the arteries, suggesting that stenting nowadays is a very robust procedure in terms of revascularization.”

In follow-up, 11.3% of patients who underwent complete revascularization were rehospitalized for ischemia-driven revascularization compared with 13.0% of patients who had only the infarct-related artery treated during the index admission, a nonsignificant difference. In the landmark analysis from 12 months to the end of follow-up, there was no significant difference in the rates of ischemia-driven revascularization between the two study groups.

“If this study had been done perhaps 10 years ago, any advantage from complete revascularization may have been balanced by the disadvantage of restenosis or even stent thrombosis in the non-infarct-related artery,” said Gershlick.

Long-term Follow-up to Confirm COMPLETE

The CvLPRIT trial, originally published in 2015, included 296 patients with STEMI and multivessel disease from seven centers in the United Kingdom randomized to in-hospital complete revascularization or primary PCI of the infarct-related artery only. Complete revascularization was performed at the time of primary PCI or before hospital discharge. As previously reported, complete revascularization lowered the risk of the primary composite endpoint of all-cause mortality, recurrent MI, heart failure, and ischemia-driven revascularization at 12 months.

The need for ischemia-driven revascularization was very low in all the arteries, suggesting that stenting nowadays is a very robust procedure in terms of revascularization. Anthony Gershlick

In long-term follow-up, there remained a significant advantage for complete revascularization in terms of the primary endpoint (HR 0.57; 95% CI 0.37-0.87). Individual components of the composite endpoint all favored complete PCI, but the differences compared with infarct-related-artery PCI only were not statistically significant. However, the combined endpoint of death/MI was reduced 53% among patients who underwent complete revascularization (HR 0.47; 95% CI 0.25-0.89).

Overall, “the study confirms the hard endpoint data we saw in COMPLETE,” said Gershlick.

In that trial, which was presented in September at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2019 Congress, lead investigator Shamir Mehta, MD (McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada), showed that complete revascularization in STEMI patients presenting with multivessel disease reduced the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or MI, as well as the risk of cardiovascular death, MI, or ischemia-driven revascularization, over a median follow-up of 3 years.

Kevin Bainey, MD (Mazankowski Alberta Heart Institute, Edmonton, Canada), one of the COMPLETE investigators, called CvLPRIT a “well-executed trial,” adding that the long-term data are a welcome addition to the field. He pointed out that the primary endpoint was quite broad and wasn’t powered given its size to detect a difference in the “Holy Grail” endpoint of death or MI after 12 months. COMPLETE, on the other hand, included more than 4,000 patients with a median follow-up of 3 years.

“Our trial was built on the background that we needed to answer this question based on irreversible hard endpoints,” Bainey told TCTMD. He views COMPLETE and the long-term follow-up from CvLPRIT as “complementary,” with both studies showing an advantage of complete revascularization in STEMI patients in terms of reducing mortality and MI.

In 2018, a meta-analysis that included nine randomized trials of STEMI patients—including CvLPRIT, DANAMI-3-PRIMULTI, and PRAMI, among others—showed that complete revascularization was associated with lower long-term risks of cardiovascular mortality, MI, and repeat revascularization.

Currently, the ESC guidelines suggest that complete revascularization be considered in STEMI patients with multivessel disease during the index hospital admission (class IIa, level of evidence A). US guidelines also state that complete revascularization could be considered during the index admission, either at the time of primary PCI or as part of a planned staged procedure (class IIb, level of evidence B-R).

In an editorial, Guillaume Cayla, MD, PhD, and Benoit Lattuca, MD, PhD (Université de Montpellier, Nîmes, France), state that in light of the data, “it is clear that complete revascularization including nonculprit lesions is superior of the culprit lesion only, not solely on ischemia-driven revascularization, but also on hard endpoints such as the composite of cardiovascular death and MI.” The results of CvLPRIT, along with COMPLETE and other trials, could warrant an upgraded and stronger recommendation for complete revascularization in this setting, they write.

When to Intervene?

As for the optimal timing of treating the non-infarct-related artery, Gershlick said their data suggest that patients should undergo complete revascularization at the time of the index admission. He pointed out, however, that data from COMPLETE showed the benefits of opening the infarct- and non-infarct-related arteries were seen whether the second procedure was done during the initial hospitalization or several weeks after discharge.

“The trouble with that [analysis] is that the investigator was allowed to decide on whether to do the procedure or to bring the patient back,” said Gershlick. “Any time you have an operator bias like that it’s hard to be sure quite sure what the data mean. Having said that, there is certainly a strong signal from their data that there’s no significant difference in benefit whether you do [the non-infarct-related artery] predischarge or bring them back shortly after.”

Bainey said their practice shifted immediately following COMPLETE, with operators now performing complete revascularization via a staged approach for all STEMI patients with obstructive multivessel disease. He also cited the data showing that the second procedure can wait a couple of weeks, which is an advantage in Canada where the cath labs are centralized and there is a high demand.

“We fix the culprit lesion and if the other lesions are stable, because of the demand of our cath lab, we’re discharging them and bringing them back for outpatient staged PCI within 45 days,” said Bainey. Like the editorialists, he said the guidelines could be due for upgrade in light of recent studies.

As for the mechanism underlying the reduction in death/MI, Gershlick pointed to an optical coherence tomography (OCT) subanalysis of COMPLETE, noting that 47.3% of patients who underwent imaging of the non-infarct-related artery had a thin-cap fibroatheroma. The hypothesis is that there is an ongoing inflammatory process in STEMI and those obstructive multivessel disease might represent a high-risk patient group. If the nonculprit lesion is vulnerable as shown on OCT, it would make sense for there to be a reduction in hard clinical endpoints by stabilizing the lesion with PCI, said Gershlick.

In their editorial, Cayla and Lattuca call for an individualized patient-centered approach when deciding on PCI for the non-infarct-related artery, noting that age, patient characteristics, and clinical details need to be factored into the decision. For example, it would be wise to avoid futile complex procedures in very old or frail patients. Also, treating the culprit lesion only in STEMI patients in cardiogenic shock is the right approach rather than complete revascularization, as shown in CULPRIT-SHOCK. Lesion severity, complexity, and operator experience also are factors that should be taken into account.

At their center, nonculprit lesions are assessed angiographically, but Bainey said one of the big questions is whether there is a difference in clinical outcomes among patients undergoing complete revascularization for lesions assessed angiographically versus those assessed with physiological testing, such as fractional flow reserve. In the future, practice may evolve to where physicians refine the characterization of nonculprit lesions, such as with OCT or other imaging, he noted.

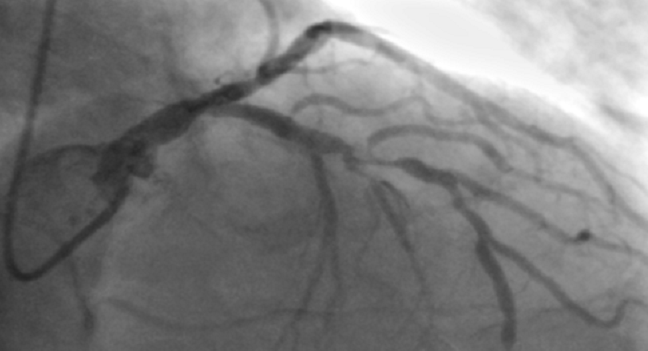

Photo Credit: Gershlick AH. CvLPRIT: Long-term follow-up from a randomized trial of early complete revascularization in patients with acute myocardial infarction and multivessel disease. Presented at TCT 2018. September 22, 2018. San Diego, CA

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Gershlick AH, Banning AS, Parker E, et al. Complete versus lesion-only revascularization in patients with STEMI and multivessel disease: the CvLPRIT trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:3083-3094.

Cayla G, Lattuca B. Long-term outcomes on multivessel disease STEMI patients: which is the culprit lesion? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:3095-3098.

Disclosures

- Gershlick and Bainey report no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Cayla reports research grants/lecture fees from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Medtronic, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

- Lattuca reports research grants from Biotronik, Daiichi-Sankyo, Fédération Française de Cardiologie, and the Institute of Cardiometabolism and Nutrition; he reports consultant/lecture fees from Daiichi-Sankyo, Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, and Novartis.

Comments