Endpoint Reporting in Medical Journals Needs to Be Revamped: Review

Focusing on P values broadly paints trials as positive or negative, leading to an unnuanced view of the findings, researchers say.

A more-nuanced approach to reporting and interpreting data from randomized controlled trials, one that factors in the totality of the evidence, is warranted in cardiovascular medicine, according to a new review.

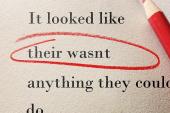

At this juncture, statistical P values are being largely misused, specifically the cutoff of 0.05 to decide whether an intervention is positive or negative, argue Stuart Pocock, PhD (London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, England), and colleagues in an article published in the August 24, 2021, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

To TCTMD, Pocock said that clinical trialists, reviewers, and medical journals need to stop their obsession with using the P value as a decision tool, which is never how it was meant to be used. “P values reflect the strength of the evidence—the smaller the P value, the stronger the evidence for any given endpoint,” he explained.

Gregg Stone, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), one of the review’s authors, said the P value has taken on a misunderstood level of importance in the world of RCTs.

“At some point, one needs to make an interpretive decision as to whether the trial findings reject the null hypothesis, usually being that there is no difference between the two therapies,” he said. “Since we don’t randomize an infinite number of patients, we are, by definition, getting an incomplete answer. The strength of the evidence then is what’s important to interpret the data. The P value is actually a really good measure of the strength of the evidence—the lower the P value, the stronger evidence that you can be confident in rejecting the null hypothesis.”

P values, said Stone, are not the “enemy,” but misinterpreting the number can lead to a misunderstanding about how to appropriately interpret clinical trial evidence. At present, P values are rarely interpreted beyond the binary of classifying endpoints as positive or negative. As an example, Stone cited the two competing trials of transcatheter mitral valve repair for heart failure patients with secondary mitral regurgitation: COAPT, which he led, and MITRA-FR. While there was no significant difference in the primary effectiveness endpoint between medical therapy and transcatheter mitral valve repair in MITRA-FR, the COAPT trial was positive with a high degree of certainty, said Stone.

The P value is actually a really good measure of the strength of the evidence Gregg Stone

“Some researchers have said that we need a tiebreaker,” said Stone. “But that’s not the case—when you look at the P value for the primary endpoint in COAPT, it’s 0.000006. At 3 years, for the reduction in death or hospitalization for heart failure, the P value has 12 zeroes followed by a one, meaning that the level of evidence is so incredibly strong it almost can’t be due to chance. Rather than saying we need a tiebreaker to see if the therapy works, clearly it ‘worked’ in COAPT because the level of evidence was so strong. The appropriate question should then be why was transcatheter mitral valve repair so effective in COAPT as opposed to MITRA-FR? That can help inform clinical decision-making.”

Sanjay Kaul, MD (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA), who wasn’t involved in the review, said the group’s recommendations make a lot of sense, noting that many of their suggestions track with those from the US Food and Drug Administration. He also agreed with their criticisms of how P values are currently interpreted.

“Just because you make the cutoff of 0.05 doesn’t make it an important endpoint,” said Kaul. “You have to look at the effect size; you have to look at the precision or width of the confidence interval. You also have to look at the unmet need and whether there are alternative agents available. You have to put it all together. . . . In general, P values overestimate the strength of evidence. What the group is proposing is a reasonable way of interpreting the evidence. If you have an extremely robust P value, the evidence is stronger. If you have a borderline P value, the evidence isn’t necessarily stronger, but it does need to be put into [clinical] context.”

Mixed Bag of Statistics

Beyond P values, however, the new review also explores strategies for reporting the primary and secondary outcomes from randomized trials. To get the lay of the land, the reviewers surveyed all cardiovascular RCTs published in the New England Journal of Medicine, Lancet, and JAMA in 2019. Of 84 RCTs, 43 were studies of a pharmaceutical intervention, 21 were device trials, 18 were patient-management interventions, and two were surgical studies. Roughly half were sponsored by industry.

In total, 89% of the studies had a single predefined primary endpoint and 11% had two co-primary endpoints. Of the 75 RCTs with a single primary outcome, a composite endpoint was used in 37 studies. For those with a composite, mortality—either CV or all-cause—was part of the endpoint in each study. All but one of the RCTs prespecified multiple secondary endpoints. However, 75% of the RCTs with secondary outcomes had no formal correction for multiple testing, while 21% of studies, mostly industry-funded trials, had a predefined hierarchy for testing secondary endpoints.

“It’s a bit of a mess what people actually do in terms of choosing their primary and secondary endpoints and whether they have any strategy for putting them in a hierarchy or not,” said Pocock. “Every trial seems to be making a different set of choices. The journals also seem to be unduly obsessed with a P value of less than 0.05 for the primary endpoint. If you don’t reach that, you’re not allowed to make a claim for a positive trial. It’s a bit silly to be so constrained by an arbitrary level of statistical significance.”

Kaul, an expert in trial design, said clinicians are typically more concerned with the totality of clinical evidence, whereas biostatisticians tend to be more wedded to statistical principles. Federal law pertaining to the approval of drugs and devices is not based on P values, he pointed out, but instead calls for adequately powered and controlled clinical studies that provide “convincing evidence of effectiveness.”

“It’s a qualitative assessment, not necessarily a quantitative assessment,” said Kaul, referring to the FDA’s interpretation of data.

In terms of how RCTs are reported, specifically the adjustment for multiplicity, Kaul said the survey highlights inconsistencies across three high-profile medical journals. Multiple secondary endpoints increase the risk for type 1 error, which is a rejection of the null hypothesis even though the differences between two treatments could be due to chance. To avoid this, investigators adjust for multiple comparisons, and the FDA has provided guidance on how and when to do so.

The journals also seem to be unduly obsessed with a P value of less than 0.05 for the primary endpoint. Stuart Pocock

The medical journals also have different policies and guidelines for statistical adjustment and reporting results. For example, NEJM restricts reporting P values only for prespecified endpoints where trialists adequately control for type 1 error. Additionally, P values for secondary endpoints are not allowed; only the point estimate and confidence intervals can be included. The Lancet, on the other hand, doesn’t have such restrictions on reporting P values.

Kaul said the medical journals and the FDA are inconsistent in enforcing their own rules. For example, NEJM allowed the EXCEL researchers—led by Stone along with Pocock, who chaired the statistical committee—to conclude there was no difference between PCI and CABG surgery for left main CAD at 5 years, even though those results were hypothesis-generating and exploratory, as the authors acknowledged. If the journal followed its own rules, that conclusion, which appeared in the abstract, should not have been made, said Kaul.

Asked about this, Stone said no rule covers every situation. “I can’t speak for the New England Journal of Medicine editors, but the primary powered outcome measure in EXCEL was the composite of death, stroke, or MI at 3 years. Thus, while this outcome at 5 years was technically hypothesis-generating, it is reasonable to accept that the point estimate and 95% CI for the long-term data for this endpoint be afforded more weight than for other underpowered outcomes, as the editors allowed.”

The 5-year EXCEL results also led to an extended back-and-forth between surgeons and interventional cardiologists, particularly around the difference in all-cause mortality favoring surgery. To TCTMD, Stone stressed again that EXCEL was only powered for outcomes at 3 years, no further.

“The primary endpoint was powered for noninferiority at 3 years—that was it,” he said. “We weren’t powered for any 5-year endpoint, so technically all of those endpoints were exploratory, observational, and hypothesis-generating. Most people don’t understand this critical point even though we made it very clear in the manuscript. Moreover, one cannot apply the 3-year noninferiority margin for 5-year outcomes when event rates are greater. Had we wanted to test noninferiority at this time, a different (wider) margin would have been chosen.”

Advocating for Flexibility

For the conclusion section of any research paper, there are strict rules about what trialists can and can’t say about their results. To TCTMD, Pocock said this policy should be relaxed to reflect the totality of the study’s evidence, including secondary and safety outcomes and not just its predefined primary endpoint.

“That would be going back more towards what I would call healthy statistical science,” said Pocock. As it stands now, trialists are in a “straitjacket” when it comes to the conclusions, with the study crudely characterized as positive or negative based on the primary endpoint, he added.

Stone noted that many of the journals have different policies, all of which are well-meaning and intended to help the average reader put the trial into proper light.

“I give the New England Journal of Medicine a lot of credit because they’ve really taken on the issue of the misinterpretation of P values head-on,” said Stone. “They’ve come up with a policy that reflects the view of many statisticians—to avoid false positive declarations, the presentation of P values should be limited to the endpoints that were adequately prespecified and powered to be tested against the null hypothesis, controlling type 1 error. I respect this approach.”

It’s a qualitative assessment, not necessarily a quantitative assessment. Sanjay Kaul

Nonetheless, if the journal publishes numerous point estimates and the confidence intervals for some exclude unity, somebody might just as easily interpret those as significant differences, knowing that the P value would be less than 0.05.

“A purist might just as strongly argue that we shouldn’t even include point estimates and confidence intervals for all nonpowered, nonprespecified secondary endpoints,” said Stone. “On the other hand, scanning a list of P values is a simple way to focus the reader’s attention on endpoints warranting further consideration,” he added. “Lastly, suppressing interaction P values obscures recognizing potential important differences in risk between subgroups, although all such findings should be considered exploratory.”

In their review, the group proposes publishing all the P values, highlighting in bold only those that were prespecified and controlled for type 1 error. In other instances, the P value could be downgraded using a lighter type, or a note could be added stating the findings should be considered hypothesis-generating and exploratory only.

As for whether journals should adhere to a universal reporting standard, Kaul said he would like them to remain flexible in terms of what they allow to be reported and/or stated in the conclusions. “I wouldn’t want to see them become too formulaic,” he said. Pocock agreed, stating that doing so would only put the journals into a different type of bind that allowed limited flexibility.

Note: Stone is a faculty member of the Cardiovascular Research Foundation, the publisher of TCTMD.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Pocock SJ, Rossello X, Owen R, et al. Primary and secondary outcome reporting in randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;78:827-839.

Disclosures

- Pocock reports consulting for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Edwards, Medtronic, and Vifor.

- Stone reports receiving speaking honoraria from Cook and Terumo; serving as a consultant for Valfix, TherOx, Vascular Dynamics, Robocath, HeartFlow, Gore, Ablative Solutions, Miracor, Neovasc, V-Wave, Abiomed, Ancora, MAIA Pharmaceuticals, Vectorious, Reva, and Matrizyme; and owning equity/options in Ancora, Qool Therapeutics, Cagent, Applied Therapeutics, the Biostar family of funds, SpectraWave, Orchestra Biomed, Aria, Cardiac Success, the MedFocus family of funds, and Valfix.

Comments