Evinacumab Lowers Triglycerides in Severe Hypertriglyceridemia

Results for this phase II trial, though promising, were variable and confined to certain patient subsets.

For those in whom the drug could be expected to work, however—and investigators see a potential role for genetic testing here—evinacumab could have a big impact, they say.

“These individuals suffer tremendously, not only from chronic abdominal pain and the need to be on a very strict low-fat diet, but also with each episode of acute pancreatitis they injure the pancreas resulting in either exocrine insufficiency malabsorption and/or endocrine insufficiency and insulin dependent diabetes,” said Robert Rosenson, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), who presented the data today in a late breaking clinical trials session at the American College of Cardiology 2021 Scientific Session.

“We want to do everything we can to prevent recurrent attacks on the pancreas,” he told TCTMD.

The fully human monoclonal antibody inhibitor of angiopoietin-like protein 3 (ANGPTL3) was approved in February by the US Food and Drug Administration as an adjunct LDL cholesterol-lowering therapy for patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (HoFH) following the publication of 2020 data showing drastic reductions with few side effects. The effects on triglycerides, however, remain under study.

Results by Genotype

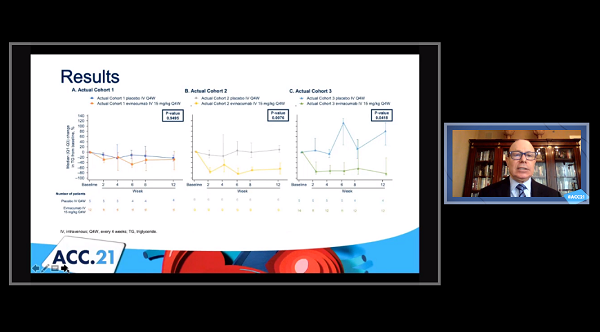

For the study, Rosenson and colleagues included 51 patients with severe triglyceridemia (defined as fasting triglycerides ≥ 500 mg/dL) who were on diet therapy and maximally tolerated lipid-lowering therapies and stratified them by genotype:

- Cohort 1 (n = 17): FCS with bi-allelic loss-of-function mutations in APOA5, APOC2, GPIHBP1, LMF1, or LPL

- Cohort 2 (n = 15): Multifactorial chylomicronemia syndrome (MCS) with known heterozygous loss-of-function mutations in APOA5, APOC2, GPIHBP1, LMF1, or LPL

- Cohort 3 (n = 19): MCS without LPL pathway mutations

Patients were randomized in a 2:1 fashion to intravenous evinacumab 15 mg/kg every 4 weeks or placebo for an initial double-blind treatment period. Following that, all patients were treated with evinacumab for an additional 12-week, single-blind treatment period. Patients were then followed for safety outcomes for an additional 20 weeks.

Demographics and baseline characteristics were well balanced. Notably median baseline fasting triglycerides were well over 3,000 mg/dL for FCS patients and ranged between 1,000-2,000 mg/dL for cohorts 2 and 3.

After the initial 12-week, double-blind study period plus the 12-week, single-blind treatment period, the least-squares mean reduction in triglycerides was 27.1% from baseline with evinacumab in cohort 3, with a corresponding median reduction of 68.8% or 905 mg/dL. Likewise, there were clinically meaningful reductions in median triglyceride level during the initial double-blind period with evinacumab versus placebo in cohorts 2 (-64.8% vs 9.4%; P = 0.0076) and 3 (-81.7% vs 80.9%; P = 0.0418). No effect was seen in cohort 1 (P = 0.9495).

Additionally, cohorts 2 and 3 saw substantial reductions in non-HDL-cholesterol, Apo-CIII, and ApoB48 over 12 weeks. These results were sustained in the single-blind treatment period as well.

“What this study tells us . . . is that genotyping is an important determinant of the response to therapy,” Rosenson said. “In those individuals with complete loss of function in lipoprotein lipase or related genes, the medication doesn't work. But in other individuals it works well.”

Safety was good with treatment emergent adverse events occurring similarly in the evinacumab (71.4%) and placebo (68.8%) arms throughout the length of the study. Serious adverse events were reported in 11.4% and 18.8%, respectively, including acute pancreatitis in two placebo and three evinacumab patients.

“Most acute pancreatitis events occurred in the off-drug period more than 4 weeks after the last evinacumab dose, at a time when the triglycerides had increased towards pretreatment levels and evinacumab concentrations had fallen to subtherapeutic levels,” Rosenson explained, adding that this likely means the 15 mg/kg dose of evinacumab wasn’t sufficient for many of these patients.

The planned phase IIb trial of evinacumab will use a dose of 20 mg/kg intravenous every 4 weeks with the goal of preventing acute pancreatitis, he said. “If we can demonstrate a therapeutic response, which we did in many of the patients and that showed a decrease in pancreatitis, this would be the first therapy proven to reduce triglyceride mediated acute pancreatitis.”

During a press conference, Sahil Parikh, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY), commented that “this patient population is a vexing group of patients, and it will be important to see what your dose-finding studies in your next phase IIb study show us in terms of getting the dosing right. If one can actually get these patients out of trouble, it'll be a boon to this selected group of patients.”

For now, Rosenson recommends FCS patients, who make up about one in 600,000 of the population, be treated with an APOC3 inhibitor in addition to a strict diet. “Even though evinacumab in our study lowered Apo-CIII by 80%, it didn't work well in the FCS patients. But for some reason, Apo-CIII inhibitors do work,” he said.

For patients like those in cohorts 2 and 3, who are much more common at about one in 5,000, Rosenson said he would pick evinacumab “because it lowers the concentration of atherogenic lipoproteins—so it's more than a triglyceride lowering agent.”

Cost will definitely be an issue, since evinacumab is projected to cost $450,000 per patient per year, but Rosenson said the prevention of pancreatitis will likely be worth it in the end. “For these individuals who have had an episode of pancreatitis, this therapy may be highly effective and potentially lifesaving for them,” he suggested. “That would be the population that would derive benefit from the therapy. So we need to think about hospital costs and also the patient's quality of life and some of their other functioning and interactions because their diet has to be so restricted.”

Effect on Other Biomarkers

In discussion following the presentation, Pam Taub, MD (University of California San Diego, La Jolla), said that the study showed a “very impressive reduction in triglycerides with evinacumab. Similar to PCSK9 inhibitors, evinacumab is a marvelous example of how a drug can be developed by mimicking natural genetic mutations in lipid metabolism that we observe in populations.”

She pointed out that prior studies of evinacumab in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia showed decreases in HDL of up to 30%. “In this trial,” Taub asked, “was there a decrease in HDL? And how do you think a decrease in HDL may translate into cardiovascular outcomes?”

Rosenson said this analysis did demonstrate a reduction in HDL cholesterol as well as in ApoA1. “Further work is needed to explore the HDL subclasses and the HDL proteome, HDL function as a determinant whether the endothelial lipase effect of evinacumab has any meaningful impact on the atheroprotective properties of HDL,” he said. “The HDL field was of course thrown into disarray by the mendelian randomization study that showed that HDL cholesterol was not involved in the causal pathway for coronary heart disease when that pathway involved endothelial lipase. Further work is needed to explore that hypothesis, particularly the variable effect of drugs such as evinacumab.”

Parikh said this is something that will be especially “important to understand as a countervailing force with respect to cardiovascular event reduction and not just pancreatitis event reduction.”

Taub also asked about the potential impact of evinacumab to upregulate the LDL receptor given that prior research has shown that its effects have been independent of the number of functioning LDL receptors.

In last year’s HoFH data, Rosenson said, they “had the opportunity to include patients who were homozygous for loss-of-function mutations in the LDL receptor and some of those individuals had LDL receptor activity less than 2%. There was equivalent LDL cholesterol-lowering in those individuals compared to those without those loss-of-function mutations, supporting the fact that evinacumab lowers LDL cholesterol by an LDLR-independent pathway.”

Lastly, Taub inquired whether evinacumab could be expected to go beyond triglyceride lowering and also decrease inflammatory biomarkers similar to what icosapent ethyl (Vascepa; Amarin) has demonstrated.

“The effects of evinacumab on inflammatory biomarkers requires further study,” Rosenson responded. “There are preclinical studies that demonstrated reduction in inflammation, not only endothelial inflammation but monocyte proliferation, with evinacumab. Human studies are important and require further study.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Rosenson RS. A phase 2 trial of the efficacy and safety of evinacumab in patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia. Presented at: ACC 2021. May 16, 2021.

Disclosures

- The study was funded by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

- Rosenson reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments