Expired Cardiac Devices May Do Global Good, but Safety Unknown

A discussion of the ethics of using expired technology in parts of the world with no other options is long past due, some say.

“She was miserable,” he told TCTMD, adding that her family could not afford the cost of the devices. “She had venous failure, venous insufficiency. She had no other options.” Without treatment, “she probably would have a miserable life,” he stressed.

Alaswad, who is now at Henry Ford Hospital & Health System (Detroit, MI), booked a ticket to his home country, asked his cath lab manager for any expired devices slated for the garbage, and packed several peripheral stents and other equipment in a suitcase with his clothes. Then he traveled halfway across the globe to help.

“Now she is a mother of three, and she's doing great,” he reported.

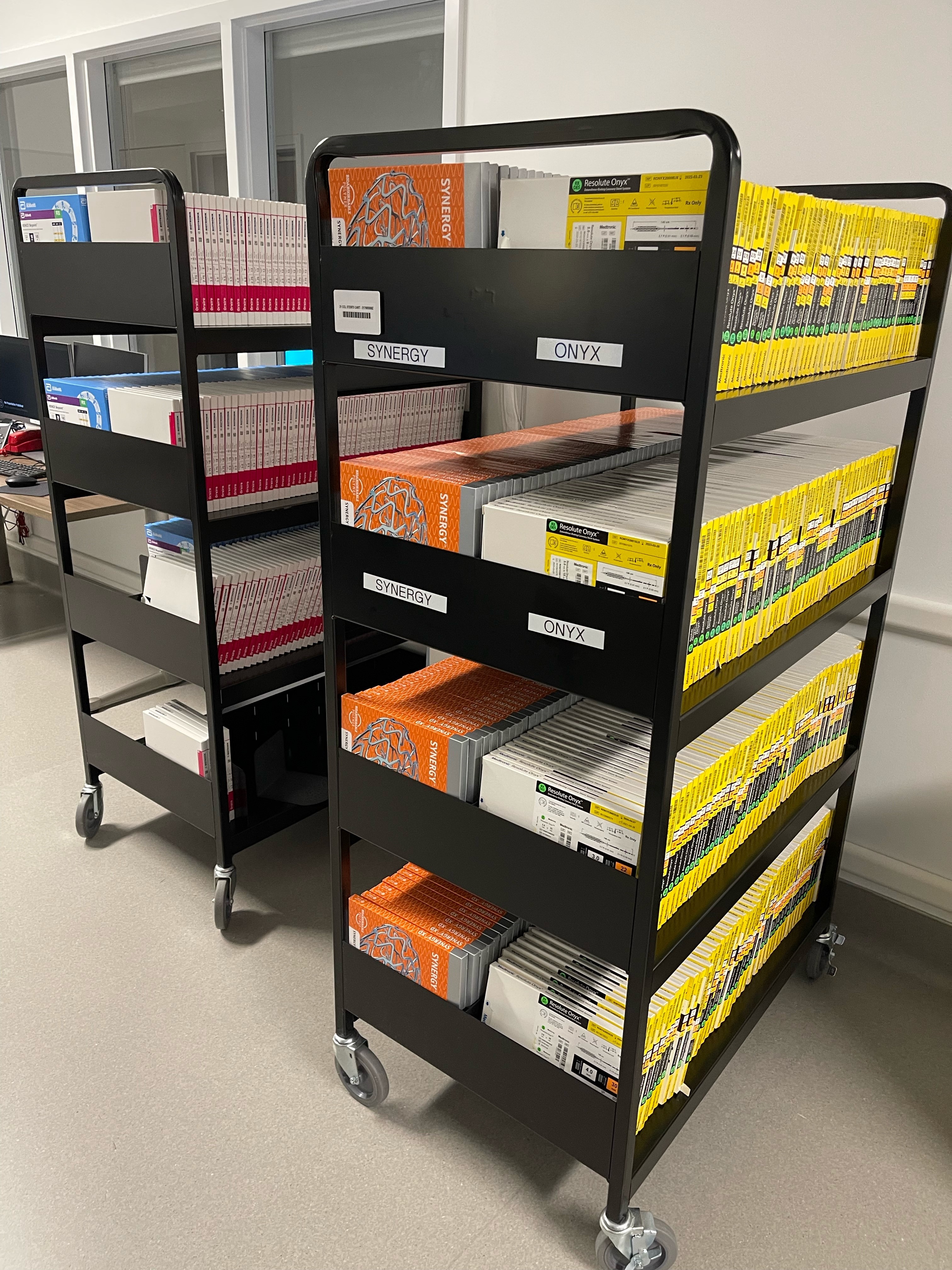

The idea of using expired products stemmed from realizing that some of the stock in his own cath lab was past its due date. “Sometimes what happens is we have devices we don't use—we don't use them, and we don't replace them,” Alaswad said. “So you look at the shelf and you discover that they've been expired for a year and a half or 2 years.”

The scope of such waste in the United States is large, said Steve Miller, RN, the CEO and founder of Medical Materials, which resells a variety of expired medical devices including catheters and stents for nonclinical use. “There are probably hundreds of thousands of devices that end up being expired and thrown in the garbage every year in US hospitals, and I felt like there were uses for them,” he told TCTMD, citing his motivation for starting the company a decade ago.

There are probably hundreds of thousands of devices that end up being expired and thrown in the garbage every year in US hospitals. Steve Miller

In his previous work as a cath lab and electrophysiology nurse, Miller said part of his job was to go through inventory every 6 months in order to throw away expired product and bring devices near expiry to the front of the shelf. “There are like thousands of items in a busy cath lab, because there are so many different manufacturers, models, sizes, and shapes. There is just a ton of stuff,” he said.

Earlier this summer, Khalid Aljohani, MD (King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz University Hospital, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), looked around the inventory storage room of a private hospital he sometimes consults at, and for the first time he wondered about what happens to all of the expired devices.

“I noticed there were a lot of expired items in one of the labs and one of my technicians said, ‘Just give it to charity,’” he recalled to TCTMD. “I doubted that is it, first, legal? Two, is it ethical? Is it safe, too? Do we know if the safety and efficacy of these stents are valid beyond their expiry dates? Or if it's just labeled because of manufacturer requirement by agencies and governmental institutions that [necessitate] an expiry date? What if some things are not meant [to expire]?”

This prompted him to head to Twitter to ask what physicians do with their expired cardiac devices. The tweet was met with more questions than answers.

“I asked different companies about protocol, and I looked it up online,” Aljohani said. It seems “some just dump them out,” but he suspects some devices get repackaged and resold.

What Happens as Devices Age?

All medical devices marketed in the United States have expiration dates set by their manufacturer based on the same data that Food and Drug Administration regulators use to approve them in the first place. Some research has shown that certain cardiac devices, like pacemakers and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs), can safely be reused. The evidence is limited, though, and several sources said future studies are unlikely to look at the potential outcomes of using expired stents, for example.

To TCTMD, Ben Petok, a spokesperson for Medtronic, specified that expiration dates are “determined by a number of scientific factors, including sterilization, and material and/or component shelf-life considerations.” The former is “part of the regulatory filing and approval for all products,” he explained in an email, while for “cases of component or material-based expiration, testing is conducted to demonstrate the shelf life of the specific material or component (eg, drug stability testing or battery life testing).”

Speaking on behalf of Boston Scientific, Laura Aumann similarly wrote by email “the testing to determine expiration dating includes analysis under ageing conditions such as high temperature, humidity, and stress to determine susceptibility of devices to environmental factors that might lead to functional changes in the device over time. There is not one set of parameters for all devices—many factors are considered and may include sterility testing, battery longevity, material properties/characteristics, packaging durability, storage conditions, and other potential performance factors.”

Abbott, the third big player in the US stent market, did not respond to requests for comment before this story went to print.

B. Hadley Wilson, MD (The Sanger Heart & Vascular Institute/Atrium Health, Charlotte, NC), speaking on behalf of the American College of Cardiology, commented to TCTMD that “most feel the product is viable longer than printed” and that expiration dates may even be conservatively shortened due to safety concerns, perhaps even to promote quicker turnover of devices.

Likewise, David Kandzari, MD (Piedmont Heart Institute, Atlanta, GA), who has worked both for the FDA and industry in the past, said: “My expectation is that like many pharmaceutical products, most if not all device technologies are just as suitable for use after the expiration date.” He noted to TCTMD that DES expiration dates, for instance, are more likely based on the drug component as opposed to the device framework, and that they’re “more a result of testing timelines and data submitted to FDA rather than actual product degradation.”

My expectation is that like many pharmaceutical products, most if not all device technologies are just as suitable for use after the expiration date. David Kandzari

But medical devices aren’t made to last forever. Ori Ben-Yehuda, MD (Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY), stressed to TCTMD that while much remains unknown in terms of what happens to coated stents as they age, “there's obviously concern over degradation of the polymer in polymer-coated stents as well as reduction in efficacy of the drug that's coated.” Sterility also could be of concern if the device packaging has exceeded its shelf life.

Miller recalled a case about 20 years ago where the tip of a stent “broke off” during implantation, only for the team to realize the device had been expired for about 2 years. “That is a definite concern: that some of . . . the nonmetalic components of the devices can potentially break down over time and it can be dangerous,” he noted.

No one who spoke with TCTMD for this story could recall a case where use of an expired device led to a bad outcome.

“While the risk [of using expired stents] is probably not great, we simply don't know and often there isn't enough data, so it creates a real ethical conundrum,” Ben-Yehuda said citing the potential increased risk of stent thrombosis, restenosis, and infection. “One has to ask oneself what is the greater risk: lack of treatment or of any degradation of the product? And I don't think we have the answer.”

How and When Devices Are Used

The US Food and Drug Administration prohibits clinical use of expired devices within the United States but takes a softer stance internationally.

“Generally an FDA-approved or cleared device can be exported without prior notification to FDA, and it will be subject to the laws of the country into which it will be imported,” an agency spokesperson told TCTMD. “A device that has marketing approval or clearance and is introduced to market beyond its labeled expiration date might be considered adulterated or misbranded in the United States.

“Such adulterated or misbranded devices may be exported if they (1) accord to the specifications of the foreign purchaser; (2) are not in conflict with the laws of the country to which they are intended for export; (3) they are labeled on the outside of the shipping package that they are intended for export; and (4) they are not sold or offered for sale in domestic commerce,” they explained. “A device that does not have FDA marketing approval or clearance must meet certain additional requirements as well to be exported.”

Contacted by TCTMD, Jim Jeffries, a spokesperson for AdvaMed, the medical device trade association in the United States, said only that the organization “fully supports” the FDA’s position on expired devices in the US. It doesn’t have a specific stance on international usage.

Wilson is not aware of any US laws that would prohibit people from taking expired devices from their institution’s inventory and bringing them out of the country for donation, but added that he personally didn’t think this was “good practice.”

That said, he continued, “if my institution was aware and wanted to donate it and got permission from the company and so forth—if they did the proper dotting of i’s and crossing of t's—I think it might be reasonable [but only] if the country where it's going to was also accepting of that to use it within a certain period of time. I certainly don't think anything should be done under the table. . . . There is now enough support from companies, and also programs worldwide, that maybe a practice that happened in years past is not necessary anymore.”

One has to ask oneself what is the greater risk: lack of treatment or of any degradation of the product? And I don't think we have the answer. Ori Ben-Yehuda

Kandzari said his institution works with MedShare to take and redistribute product that has packaging defects or is nearing expiration, although the nonprofit organization doesn’t accept expired product. Wilson, for his part, highlighted MAP International, a nonprofit that receives requests from nongovernmental and other organizations.

A complicating factor, said Wilson, is that manufacturers typically have a “contractual relationship of support” with the institutions to which they sell devices. They would not be able to fulfill this arrangement if the devices were moved somewhere else without their knowledge, he said, because they’d would no longer be in a position to trace the product in the event of a recall.

Indeed, Petok confirmed that Medtronic tracks devices they manufacture to ensure that expired products are removed from circulation and not sold. Additionally, their company policy allows “for the provision of products to customers for evaluation purposes,” a category that includes devices no longer designated for patient care. “Products provided for evaluation purposes are intended for demonstration or evaluation of product capabilities and features, including to advance clinician understanding and for patient awareness and education,” he explained. “As appropriate, these evaluation products are designated as ‘not for human use.’”

Further, Petok said, “if we become aware of potential noncompliance with our requirements under these policies, we would perform an appropriate review and, if needed, take any necessary remediation steps, including employee disciplinary actions.”

Likewise, Aumann said Boston Scientific uses “clear direction in our labelling and Instructions for use to segregate expired devices so they will not be used in patients. An expired device should be disposed of by healthcare providers/facilities or returned to us to be disposed of, depending on local regulations and type of device.”

That leaves organizations and medical groups, when operating in countries in dire need, to advocate for device donations even if their sell-by dates are looming. Ahmed Suliman, MBBS (Al Shaab Teaching Hospital, Khartoum, Sudan), told TCTMD his institution has worked with organizations like the Sudanese American Medical Association (SAMA), both to secure donations of much-needed devices as well as to increase their efficiency in dealing with the associated bureaucracy and decrease the likelihood of them receiving expired product. SAMA is comprised mainly of “Sudanese professional doctors in diaspora, mostly in the US, who collect donations of devices in the US and they [are] registered over in the US and here,” he explained.

Similarly, Alaswad said he has worked with the Syrian American Medical Society (SAMS) to procure donations for mission trips in the past.

Ethical Dilemmas

If the data on the safety and efficacy of repurposing past-due devices are lacking, so too is consensus on the ethics of doing so. “Rich countries tend to think of reusing or using things that are getting close to expiration dates with a real sense that that's not a good practice. But in poor countries that have nothing, it's a very different attitude,” medical ethicist Arthur Caplan, PhD (NYU School of Medicine, New York, NY), told TCTMD. “There, there's some consensus that even though it may not be ideal, if they could get anything that would help as long as it's not horribly dangerous.”

The donation and use of expired equipment today is somewhat of “an underground practice,” said Caplan. “They're not really hiding it but they're not advertising it. . . . FDA doesn't like it. People don't like shipping products that are deemed reused but never been proven safe. They just fear that they're going to get in trouble.”

Rich countries tend to think of reusing or using things that are getting close to expiration dates with a real sense that that's not a good practice. But in poor countries that have nothing, it's a very different attitude. Arthur Caplan

While Caplan said he had never heard of someone facing penalties for using an expired device that had been donated, stories do exist of physicians in India and Italy facing legal trouble for implanting devices past expiry.

A physician using anything past expiration should always disclose that to the patient, Caplan noted. That said, the likelihood of a legal issue cropping up without such a disclosure “depends where you are in the world. A lot of these countries now don't have any malpractice. Nobody is going to be criticizing the fancy surgeon in the one hospital who could do it,” he observed.

In Sudan, for example, hospitals often face shortages of specialized or expensive devices like covered stents, pacemakers, and ICDs, but hospitals and charities supply them with donations, according to Suliman. While many regulations exist around how devices can be donated and items past expiry are not allowed, “what happens is that sometimes they bring in devices that are very close to expiry dates, so that by the time they are shipped, cleared from customs, and they come to hospitals, they are about to expire or have expired already. That's where the dilemma is,” he said. Suliman added that he sometimes feels that donors, mostly in the United States and the Persian Gulf region, are “dumping” their old device stash on them without proper communication perhaps for ego-boosting reasons.

“We don't use them if they are expired, unless it's a lifesaving procedure that there's no alternative to and [in this situation] the team would inform the patient,” Suliman continued, adding that all use of expired devices must be documented for legal purposes. “The patient will generally, obviously, not say no.”

Suliman said he “would rather not use” expired devices and has concerns over whether donations are stored properly in transit—exposure to high temperatures can melt plastic and denature proteins in DES, as examples. However, “if you work in a limited resource environment, you're used to working with whatever you have. It's part of what we do every day here,” he commented.

For Abdelsamad Adam, MD (St. Paul’s Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia), donated devices are much more heavily relied upon in his practice. He told TCTMD via WhatsApp that they primarily receive catheters, stents, balloons, and pacemakers from the United States and Korea, and while they don’t accept expired devices, many expire sitting on their shelves. They often use expired devices without telling patients. “We think it’s better to save patient life than leaving it,” he said. “We have a concern, but what to do? And there is no study also regarding these things.”

Kandzari himself said he’d taken stents, balloon catheters, and guidewires to other countries to perform procedures, as well as evaluated new device technologies in underprivileged places. “When we would perform procedures in other countries (eg, in South America), the devices were often reused and dipped in sterilization fluids in between cases,” he said in an email. “It was quite remarkable how many times over guidewires were used (and bent up, mangled) and devices that were 'hydrophilic' no longer had retained their slick, hydrophilic coating after multiple uses. We would even take expired stents, and if performing a procedure, we were limited to using just one stent and so had to pick the most diseased segment to stent and perform balloon angioplasty elsewhere.”

In recent years, Kandzari said hospitals have placed restrictions on doctors taking expired product for use elsewhere and keep “careful track” of inventory. While his institution does not currently have such a policy in place, “I'm certain this is only because they've never encountered the issue,” he said.

If you work in a limited resource environment, you're used to working with whatever you have. It's part of what we do every day here. Ahmed Suliman

Today, Wilson said device manufacturers have dedicated programs for those looking for donation of devices for charity work, negating the need for using expired product. “It's just been a natural evolution that companies are more willing to donate,” he said. Likewise, in “low- and middle-income countries that are receiving the product, their regulations are greater than they were in the past, which is appropriate.”

Petok confirmed Medtronic will donate nonexpired product “for use with indigent patients, for use with patients as part of international mission trips, [and] for research and for education.” Boston Scientific also participates “in a number of programs to donate nonexpired devices and equipment,” Aumann said. “The programs are structured to meet the varied needs of healthcare providers and patients with a range of medical conditions in the markets we serve.”

But this product stream can only provide so much. According to Miller, Medical Materials receives requests daily from people around the world wanting to purchase expired devices for clinical use.

As for what does happen to expired devices in most US cath labs, both Kandzari and Wilson said their institutions return those purchased on consignment to the vendor for recycling, but other devices are thrown in the trash.

“There are some instances in which some companies will replace with new product at a discounted price, so it's better not to throw away and then pay full price,” Kandzari said.

Lack of Evidence Either Way

Since 2007, Alaswad has participated in several mission trips, mostly to Jordan and Iraq, and although he has taken suitcases full of donated devices with him, none have been expired. Most of them he secures directly from device companies as aboveboard donations, but he has to transport them due to exclusivity agreements in the countries he travels to. This doesn’t always work out: the Iraqi customs department once confiscated an estimated $100,000 in equipment from him, said Alaswad.

Alaswad spoke of growing up in scarcity and how that has enabled him to be creative with available resources in his practice of medicine, even needing to use expired drugs in the past when practicing in Syria. “I thought of it as: we don't really have a choice,” he said. “These people cannot be offered Western medicine. Western medicine is still very, very expensive. The devices are made for the people with money, not for the 95% of the people who are poor around the world. And so we had to do what we had to do to help them. And all these patients were grateful. They did not even question it.”

The devices are made for the people with money, not for the 95% of the people who are poor around the world. Khaldoon Alaswad

To someone opposing this practice, Alaswad said he would need to see the evidence that he is doing harm before stopping any future use of expired devices on mission work. “We're going to continue to monitor the situation and if we have to [use something expired], we are going to assess the risk versus the benefit. We're going to use it if the benefit overweighs the risk,” he noted.

On past mission trips to Niger, Aljohani recalled taking stents that were near expiry for use, but he admitted he has a hard time justifying the use of expired devices without evidence of safety and efficacy. “I think we should have science to back it up if we are going to use it,” he said. “Even if the patients agree, if they said ‘Yes, give it to me,’ I will have to tell them: ‘I don't know. It might harm you.’”

Aljohani acknowledged that “unless a company volunteers their own internal data, which I highly doubt that they would do,” the true safety and efficacy of using expired services is “something that maybe is never meant to be known.”

The sheer magnitude of what is thrown away is what really irks him. “I think it's a waste, because it's expensive,” Aljohani said. “The company should at least recycle them,” though that doesn’t seem to happen. As with so many things these days, he suspects, “the cost of recycling is maybe more expensive than making new ones.”

“The waste we [produce] in the US actually could run a whole healthcare system in some third-world countries,” Alaswad agreed. “We need to be much more cognizant of our resources and how to use them and how to share them.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full Bio

Vijay Kapadia