Go Beyond Angiography in CCS to Pinpoint the Problem, Urges AID-ANGIO

A hierarchical strategy of intracoronary testing takes just minutes, researchers say, and can provide clarity on INOCA.

PARIS, France—In patients with chronic coronary syndromes (CCS), a hierarchical strategy that assesses physiology and vascular function at the time of angiography results in better diagnostic yield than angiography alone, the AID-ANGIO study demonstrates.

The most glaring example: cardiologists who used just angiography and clinical characteristics to decide whether patients had ischemia with nonobstructive coronary arteries (INOCA) were wrong fully 78.2% of the time in comparison to the stepwise approach, the new study showed.

An Advanced Invasive Diagnosis (AID) strategy, the components of which are all currently recommended by US and European guidelines, is an opportunity to better pinpoint the underlying cause of symptoms, he said.

It involves, as a first step, invasive coronary angiography to diagnose stenoses ≥ 90% on visual estimation. After that, testing is tailored to whatever results are revealed along the way.

For stenoses < 90% on angiography, physiological testing with fractional flow reserve (FFR) or resting full-cycle ratio (RFR) is used. If FFR/RFR is negative, patients then undergo vascular function tests to measure coronary flow reserve and index of microcirculatory resistance as well as acetylcholine testing, with the goal of assessing endothelium-independent and -dependent impairment.

“The most interesting finding from our trial relates to the fact that INOCA was even more prevalent than obstructive coronary artery disease” when diagnosis was informed by AID, said Adrián Jerónimo, MD (Hospital Clínico San Carlos, Madrid), who presented the results today at EuroPCR 2024. INOCA, he told attendees, “is highly prevalent in [CCS], both in patients with angiographically normal vessels and in those with functionally nonsignificant stenoses. . . . It’s not possible to make an actionable diagnosis of INOCA only based on angiography and clinical information.”

William Wijns, MD, PhD (Lambe Institute for Translational Medicine and CÚRAM, Galway, Ireland), who moderated the press conference, emphasized that the study’s simplicity shouldn’t eclipse its importance. “You see no Kaplan-Meiers, no sophisticated statistics: this is an analysis of a patient care track,” Wijns noted. “But the impact will be profound, because what happens normally is that patients would have to come back for another procedure to undergo this testing. And so that creates an extra barrier to actually reaching an appropriate diagnosis.

“What this study shows . . . is that you can do this ad hoc if everybody—the patients, treating physicians, and the teams—is prepared for it,” he commented.

AID-ANGIO

AID-ANGIO enrolled 317 all-comer patients (44% female) slated for diagnostic angiography. Based on the angiographic results, a clinical cardiologist first made a tentative diagnosis and therapeutic plan. Patients then proceeded through the AID testing, after which an “ischemia team” made a definitive diagnosis and an updated plan.

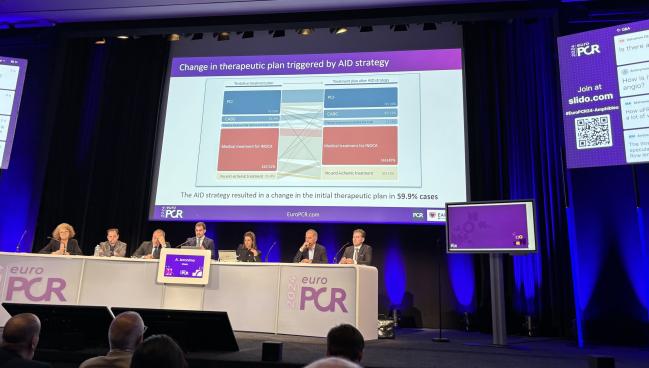

With angiography alone, obstructive CAD was identified as the cause of ischemia for 32.2% of patients and no cause was found for 67.8%. With the AID strategy, the cause was identified 84.2% of the time: 39.1% had obstructive CAD, 45.1% had INOCA, and 15.8% had no abnormalities.

Thus, AID increased the diagnostic yield by 2.6-fold (P < 0.001) and for 59.9% of patients, the results modified the initial treatment plan. The testing was safe, as well, Jerónimo reported, with two dissections and one ventricular fibrillation. It added only 15 minutes of time, on average, in the cath lab.

All of a sudden we’re saying in an all-comers study we can change the diagnosis . . . just by adding 15 minutes in the cath lab and actually performing proper INOCA testing. Matthias Götberg

Matthias Götberg, MD, PhD (Skåne University Hospital, Lund, Sweden), the presentation’s assigned discussant, described AID-ANGIO as “brilliant” but also “difficult” because it challenges preconceived notions.

“All of a sudden we’re saying in an all-comers study we can change the diagnosis . . . just by adding 15 minutes in the cath lab and actually performing proper INOCA testing,” Götberg said, noting that prior studies had been in more-selected populations, which led him to wonder how prevalent INOCA is in real-world patients with CCS. “This is really challenging on many levels and very intriguing: that we can do more.”

Jerónimo said AID-ANGIO was meant more as an investigation of diagnostics than a study of INOCA. Future studies will look at how applying the AID strategy might affect clinical outcomes and quality of life.

Escaned told TCTMD that name recognition is valuable when developing a strategy like AID. “It’s good to label it,” he said, noting that this also allows for consistency across trials. On the way is a study in the setting of post-PCI angina.

Going forward, there’s the question of whether the AID concept will encourage wider adoption of these testing modalities. “Obviously, the main challenge is the one that we’ve had already for years—still many cath labs are not using intracoronary pressure guidewires [or doing] tests to diagnose INOCA,” Escaned noted. “Hopefully, on top of all the evidence that’s coming from many other studies, this study will foster our colleagues to implement this strategy.”

If INOCA is diagnosed, he said, then treatment follows the same approach as done in the CorMicA trial, where patients are started on calcium channel blockers, statins, ACE inhibitors, and beta-blockers.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Jerónimo A. Combining angiography and pre-specified intracoronary testing in patients with chronic coronary syndromes: the AID-ANGIO study. Presented at: EuroPCR 2024. May 14, 2024. Paris, France.

Comments