‘High Index of Suspicion’ First Step in Successful Management of SCAD

A new AHA scientific statement makes it clear: SCAD is not as rare as once thought, and requires careful identification and management.

Spontaneous coronary artery dissection (SCAD) remains poorly understood, misdiagnosed, and mismanaged. Now, a group of experts is hoping to change all that with a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA).

“If you were trained more than 10 years ago, which is still a lot of young people in practice, you were taught that this condition was extremely rare, mainly happened in women, mainly happened after a pregnancy, and basically you wouldn’t see it,” Sharonne Hayes, MD (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), chair of the writing committee, told TCTMD. “What’s happened since then is a recognition that this is more common than we thought—we’ve just been missing it, angiographically and clinically—and it’s a very important cause of heart attack among women under 50.”

Missed diagnoses and mismanagement of SCAD delay early supportive care, she added, and women are disproportionately missed because the condition does occur more frequently in female patients, many of whom do not fit the profile of a typical MI patient. “We’re seeing some of the egregious oversight in [SCAD] diagnosis that we saw 20 or 30 years ago,” said Hayes, referring to days when ACS was considered to affect mainly men, and when women were underdiagnosed and undertreated.

Esther Kim, MD (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), co-chair of the AHA statement, told TCTMD that of 10 people who develop SCAD, nine of those will be women.

“In order to make this diagnosis, you need to have a high index of suspicion,” said Kim. “When a woman, particularly [one] under 50 years old, comes to the ER with chest pain you can’t ignore them, because we’ve now identified that there is a disease process that can cause myocardial infarction in patients who don’t have atherosclerotic risk factors.”

SCAD Not Always Due to Intimal Tear

In the document, which was published February 22, 2018, in Circulation, the AHA writing group reviews the epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis, initial management, and outcomes of SCAD, as well as how to evaluate and manage chest pain syndromes after SCAD. Additionally, the experts address managing pregnancy-associated SCAD; pregnancy, contraception, and hormone use after SCAD; and the management of abnormal uterine bleeding after dissection.

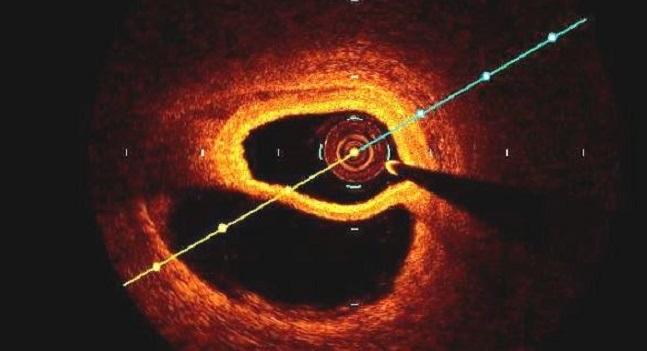

SCAD typically develops in one of two ways. In the first, an intimal tear in the vessel wall allows blood flow from the true lumen into a false lumen, which can lead to the development of an intramural hematoma that compresses the true lumen, leading to MI. In the second, the primary event is a spontaneous hemorrhage from the vasa vasorum within the vessel wall.

The prevalence of SCAD remains uncertain due to widespread under-diagnosis. Patients who survive and present to the hospital “almost universally” experience ACS, according to the statement, and have increased levels of cardiac enzymes. However, the condition most commonly occurs in younger patients with few or no traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and as such, ACS might not always be suspected.

A range of reports suggest that as many as 26% to 87% of patients with SCAD present with STEMI and 13% to 69% with NSTEMI. Ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death account for SCAD presentation in significantly fewer patients. Other data suggest SCAD might be responsible for as many as one-third of MIs in women younger than 50 years and that the condition is the most common cause of pregnancy-associated MI.

SCAD is typically diagnosed when a patient is sent for coronary angiography, but even in this setting physicians can miss it, said Hayes. “Before 10 years ago, we were told what SCAD looks like on angiography—it was a double lumen, it was a filling defect, it was visualizing a flap in the artery,” said Hayes. “What we’ve learned now with more research is that the majority of folks have a smooth, long narrowing more related to the intramural hematoma.”

Historically, such angiograms were classified as spasm, atherosclerosis, or even normal, said Hayes. For this reason, it’s important for interventional cardiologists to recognize SCAD in its many angiographic forms. The new scientific statement outlines a contemporary classification system to aid physicians.

Monitor Patients for 3 to 5 Days

Regarding treatment, PCI should be reserved only for a select group of SCAD patients as it is associated with lower technical success and higher complications when compared with PCI for atherosclerotic disease. While PCI might be necessary for unstable patients, those with a complete occlusion, or high-risk anatomy, Hayes said an invasive strategy can make things worse in SCAD patients.

“We should leave them alone and observe them for a couple of days,” she said. “There is a high degree of spontaneous healing.”

Kim added that the use of guidewires in PCI can cause an extension of the coronary dissection: the arteries of patients with diagnosed SCAD tend to be fragile and prone to additional tearing. “Any time you go in there, you are putting a person at risk who is already at a higher risk for that type of injury,” said Kim. “That’s why revascularization really needs to be for something that’s indicated, such as symptoms that can’t be controlled or other manifestations of instability.”

The new scientific statement contains a treatment algorithm for managing SCAD, with experts advocating conservative treatment, which includes inpatient monitoring for 3-5 days in clinically stable patients without high-risk anatomy, such as left-main coronary artery dissection or proximal dissections of two or more arteries. About one in 10 patients treated conservatively develops recurrent chest pain that will require coronary revascularization, said Hayes.

The experts concede there is still a lot to learn about SCAD, including how to best use medical therapy, but they advise stopping anticoagulation once a diagnosis is made. There is no consensus on the use of aspirin alone versus DAPT among those with SCAD, and no agreement on the duration of treatment after ACS. Beta-blockers have been shown to reduce the incidence of recurrent SCAD in one hospital series, they note in the AHA statement. “Most of us would use beta-blockers early on,” said Hayes.

To TCTMD, Kim said that because the disease is uncommon—and there is so much still to learn—they have initiated a large, nationwide, prospective registry known as iSCAD that will attempt to answer some important questions. With 13 hospitals across the United States participating, investigators hope to collect enough data to accurately characterize SCAD and to follow patients over a longer period of time to assess its natural history.

Kim also reminded cardiologists to look outside the heart once SCAD is identified and treated, given that these patients are also at risk for other vascular abnormalities, such as cerebral aneurysms and fibromuscular dysplasia. “It’s important to take care of the patient from the entire cardiovascular perspective,” she said.

Photo Credit: Sharonne Hayes, MD

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Hayes SN, Kim ESH, Saw J, et al. Spontaneous coronary artery dissection: current state of the science. Circulation. 2018;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Hayes and Kim report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments