High TEE Injury Rate in Structural Heart Interventions Warrants Caution

Minimizing probe manipulation, screening for anatomical abnormalities, and using new technologies may help.

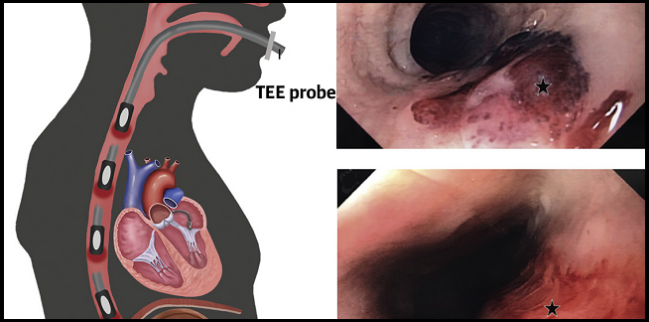

Injury associated with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is apparent in most patients undergoing structural interventions, with procedure length and image quality affecting the level of risk, according to new prospective data. Notably, no patients in the study reported clinically significant injury.

TEE is vital to guiding structural procedures like mitral and tricuspid valve repair, left atrial appendage occlusion, and paravalvular leak closure, although it has been performed less and less in TAVR as operators have begun using a more-minimal approach with conscious sedation.

“When you perform TEE in real practice in an awake or sedated patient, the patient can complain if there are difficulties or issues and you can stop the procedure,” senior author Josep Rodés-Cabau, MD (Laval University, Quebec City, Canada), told TCTMD. However, when a patient is under general anesthesia, as in most structural heart interventions, the only way an operator might know of a problem with the TEE probe is if bleeding was observed and at that point the injury could not be prevented, he explained.

TEE-associated injury “definitely is not something people talk about, mostly because there's an assumption that TEE is an intrinsic part of the procedure and you just can't get away from it,” David Cohen, MD (Kansas City, MO), who was not involved in the study, told TCTMD. “But we thought that with TAVR, and we've pretty clearly shown at this point that you can do it very safely without TEE. . . . In these old, sick, anticoagulated patients, everything less we can do is better. So that continues to be the message. Less is more as long as you can do it safely and well.”

Lessons for Future TEE-Guided Procedures

For the study, published in the June 30, 2020, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Afonso B. Freitas-Ferraz, MD (Laval University), Rodés-Cabau, and colleagues prospectively enrolled 50 patients (median age 77 years) undergoing TEE-guided structural interventions at their institution and analyzed them with esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) before and after.

Overall median procedure time was 48 minutes, with MitraClip and tricuspid valve repair times being the longest at 80 and 75 minutes, respectively. Patients stayed in the hospital for a median of 1 day, and one patient died of complications unrelated to TEE.

Less is more as long as you can do it safely and well. David Cohen

EGD revealed anatomical abnormalities in half of the patients ahead of their procedure and new esophageal injuries in 86%—40% of which were complex, such as intramural hematomas or mucosal lacerations. Those with new injuries compared with those without more frequently had abnormal baseline EGDs (70% vs 37%; P = 0.04), longer procedures (median 66 vs 42 minutes), poor or suboptimal image quality (40% vs 10%; P = 0.02), and postprocedural odynophagia or dysphagia (40% vs 10%; P = 0.01).

On multivariate analysis, independent predictors of complex lesions included longer imaging time under active probe manipulation (OR per 10-minute increment 1.27; 95% CI 1.01-1.59) and poor or suboptimal image quality (OR 4.93; 95% CI 1.10-22.02).

All patients who had injury were managed conservatively and healed without it developing into more-severe complications. No patients died, were readmitted, or reported any further TEE complications over a median follow-up period of 45 days.

“What surprised us was the high number of findings,” given other electrophysiology and pediatric studies showed the rate of injury to be closer to 50%, observed Rodés-Cabau. “This being said, most of them, however, were really minor things that have no clinical impact. . . . But I think the fact that this can happen is an important message for all people involved in these procedures.”

While all cardiologists are trained to perform TEE, study co-author Mathieu Bernier, MD (Laval University), explained that most are not familiar with the nuances of performing TEE in a structural heart setting. “We know that there's a small risk of perforation, there's a small risk of dysphasia, and stuff like that,” he told TCTMD. “But when we go for a structural guiding, it's an evolving field.”

The fact that so many patients undergoing structural procedures already have baseline esophageal abnormalities is an added challenge, Bernier added. “When we have a patient that is more likely to suffer from possible trauma associated with manipulation during guiding, we know that they're more fragile . . . and especially in those more fragile patients we'd like to try to reduce the time of imaging, reduce manipulation, and take extra time to look out for the patient if he develops any symptoms of dysphasia or stuff like that,” he said.

The authors recommend the following measures to reduce the risk of TEE-related complications:

- In evaluating any patient for a structural heart procedure, question the need for TEE and general anesthesia at the outset

- In patients with known esophageal disease, weigh the benefits and risks of performing TEE and potentially get clearance from an upper GI specialist

- Ask patients under conscious sedation to swallow while advancing the TEE probe to minimize excessive force

- When using TEE during a procedure, aim to minimize unnecessary manipulation, avoid flexing or locking the probe, freeze the image when the probe is not being used, and be judicious about stopping unsuccessful procedures with prolonged TEE times

- Use real-time 3-D spatial visualization and fusion imaging when possible

‘An Important Advance’

In an accompanying editorial, Jayashr R. Aragam, MD, and Zaid I. Almarzooq, MBBCh (both Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), write that the study “represents the first prospective analysis of gastroesophageal complications with TEE in the setting of transcatheter structural heart disease interventions utilizing both pre- and postprocedure EGD.”

The findings are “consistent with our understanding of the transcatheter interventions that usually require long periods of image acquisition and probe manipulation compared to other types of TEE-guided procedures (atrial fibrillation ablation, TAVR, and cardiac surgery),” they continue, adding that the risk profile of these patients might also lead to a higher incidence of TEE-related complications. “The exact mechanism for the esophageal and gastric injury is therefore likely multifactorial—including direct mechanical injury from blind probe insertion and manipulation, as well as probe-related contact pressure and thermal injury—and exacerbated by longer image acquisition times and an underlying, high-risk substrate.”

It would be wrong to take away from this study the mindset that a TEE-guided procedure is undesirable, Cohen noted. “There's a reason we're doing it with TEE: because it's necessary to do the imaging and the outcomes of the procedure, which presumably have been considered, are taken into account already,” he said. “What it suggests to me is that we have to be aware, we have to be sensitive and attentive to these issues, and that if there are ways to develop smaller, safer probes, [or] imaging that doesn't require transesophageal instrumentation, then those can potentially have real advantages once the imaging part of it is worked out well.”

Aragam and Almarzooq call for further study with larger, multicenter cohorts with longer follow-up to evaluate patient-centered outcomes as well as other TEE-related factors like “hospital volumes, operator experience, procedure urgency, and predisposing patient comorbidities.” Also, they write, “it may be helpful to develop a tool to assess complication risk using risk factors identified by prior studies, which can then be validated in a large prospective study.”

Cohen added that he would like to see further development of complementary technologies that will allow for complex procedures to proceed without TEE. “I know some centers are using intracardiac echo for things liked left atrial appendage closure,” he said. “I haven't really seen anything about using those techniques for mitral valve interventions, but I think they may be possible.”

“Overall, this study marks an important advance in our understanding of the complications related to TEE during structural heart interventions,” the editorialists conclude. “Also, it highlights the importance of evaluating patients’ preprocedure risk profile before deciding on an optimal imaging strategy during transcatheter interventions and adhering to guideline-directed steps to minimize the occurrence of TEE-related gastroesophageal injuries.”

Photo Credit: J Am Coll Cardiol. Central Illustration (adapted).

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Freitas-Ferraz AB, Bernier M, Vaillancourt R, et al. Safety of transesophageal echocardiography to guide structural cardiac interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3164-3173.

Aragam JR, Almarzooq ZI. Transesophageal echocardiography in structural heart interventions: is it time to rethink our approach? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:3174-3176.

Disclosures

- Freitas-Ferraz was supported by a research grant from the Quebec Heart & Lung Institute Fondation.

- Rodés-Cabau holds the Research Chair “Fondation Famille Jacques Larivière” for the Development of Structural Heart Disease Interventions; and has received institutional research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific.

- Bernier, Aragam, Almarzooq, and Cohen report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments