Infective Endocarditis Guidelines: The More the Merrier? Maybe Not

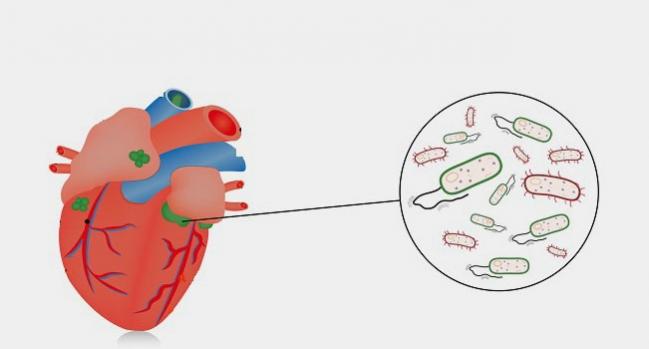

Over three cycles of guidelines, the advice for IE has gotten more extensive but less evidence-based, a new study has found.

Over recent decades, US and European groups have released more and more new or updated guidelines for the treatment of infective endocarditis (IE). But within those guidelines, the number of recommendations for treating the complex condition has increased more than sixfold without a corresponding uptick in the evidence base, researchers report in a new American Journal of Cardiology paper.

“IE is a rare but important disease, as it is related to a high mortality and morbidity. Because it is a rare disease, it is also challenging to conduct large studies, and as a result, clinical guidelines are based on a low level of evidence,” lead author Lauge Østergaard, MB (Heart Centre, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark), told TCTMD via email. Looking into the development of such recommendations is worthwhile, he explained, because “it is important to realize on what basis we treat our patients.”

Specifically, Østergaard and colleagues considered three cycles of American Heart Association (AHA) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines: the 2004 AHA and 2005 ESC documents, the 2007 AHA and 2009 ESC documents, and the 2015 iterations from both groups.

Between 2004/2005 and 2015, the number of IE recommendations within the guidelines increased from 37 to 253. Most of the growth was related to advice on treatment. Yet the proportion of recommendations classified as level of evidence A decreased from 20% to 1.6% over the same time frame (P < 0.001). Meanwhile, there was a nonsignificant drop in level B (from 48.6% to 45.9%; P = 0.29) and a significant rise in level C recommendations (from 31.4% to 53.0%; P = 0.02).

But Robert Bonow, MD (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL), who served on the writing committee of the 2007 AHA guidelines, said the shifts observed by Østergaard et al are not a sign that anything is amiss.

Commenting on the paper for TCTMD, he said IE guidelines and the evidence supporting them are “not typical,” mainly due to the difficulty in conducting randomized trials. Without this sort of formal evidence, instead there are “empiric recommendations from experts—it’s mostly consensus of opinion.”

It’s mostly consensus of opinion. Robert Bonow

The first waves of recommendations started coming out half a century ago, Bonow pointed out, so the current analysis is somewhat arbitrary in its cutoffs.

“Initially, [the advice] was anybody with any kind of valve disease required antibiotic prophylaxis,” Bonow said, adding that the doses and means of delivery changed over time. As of 2007, the guidelines suggested “not everybody with valve disease needs to receive an oral antibiotic to prevent endocarditis. [Instead they said] we should only give it to people who would be at high risk not of developing the disease but [at] high risk of having a terrible outcome if they got the disease.”

While the new analysis is “an interesting exposé on the fact that we probably need to do more, it’s not an exposé on how we do guidelines. These guidelines are kind of special,” he observed. Overall, Bonow added, they come down to “common sense.”

What Makes IE Special

Infective endocarditis “is a common enough condition that a cardiologist in practice will come upon this several times a year, and in a big medical center it’s obviously much more common,” Bonow noted.

Several factors make IE challenging to address, he said. For one, the patient population is shifting from “relatively healthy people who have valve disease and get an infection” to intravenous drug users and elderly people, who tend to be much sicker. Also, the bacteria at the root of infections are changing, which affects prevention and treatment. Finally, “newer imaging technologies have come along to help inform the diagnosis,” he added. “So, there are just lots of moving parts.”

Much like Bonow, Østergaard said that the findings should be kept in perspective. “From my point of view, it is always concerning when the evidence base is low,” he commented. “However, reasons for this low evidence base must be considered before conclusions can be drawn. Endocarditis is a very heterogeneous and relatively rare disease, [which is] why it is difficult to conduct large randomized controlled trials.”

But, he added, there are several RCTs underway. Among them is the POET study from Denmark, “which will definitely set its mark on future guideline recommendations,” Østergaard predicted. “But more are needed, and especially larger networks interested in IE need to be established in order to conduct larger and preferably randomized studies.”

What the current findings indicate, he concluded, is the “need for clinicians and researchers across national borders and clinical specialty to collaborate in large studies so that clinical decisions can be made upon a more solid evidence base in the future.”

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Østergaard L, Valeur N, Bundgaard H, et al. Temporal changes in infective endocarditis guidelines during the last 12 years: high-level evidence needed. Am Heart J. 2017;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Østergaard and Bonow report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments