Midlife Vascular Risk Factors Linked to Amyloid Plaques in Alzheimer’s

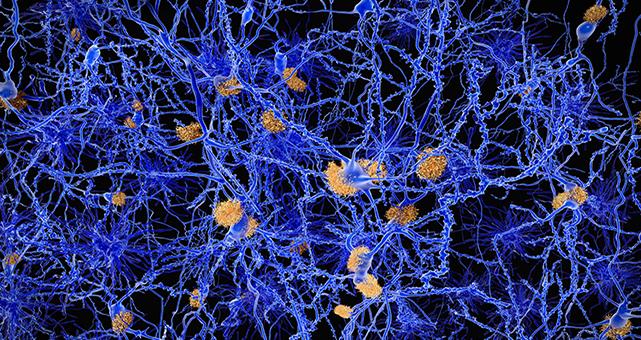

New imaging findings add heft to earlier research implicating common cardiovascular risk factors in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

In a finding that adds heft to earlier research linking vascular disease and dementia, a new imaging study suggests the same risk factors that place patients at increased odds for cardiovascular disease also contribute to the development of amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s.

Strikingly, the link was only present when vascular risk factors were seen in midlife, not later on.

These observations should provide additional impetus for aggressive early identification and management of cardiovascular risk factors, according to investigators writing in an early online publication in JAMA.

“We know from some other studies, including our own, that vascular risk factors have been associated with dementia and even Alzheimer's disease, when defined based on clinical symptoms,” lead author Rebecca Gottesman, MD, PhD (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD), told TCTMD in an email.

What is less clear, she explained, is the underlying pathology. Subclinical vascular changes in the brain can contribute directly to the development of vascular dementia, but Gottesman pointed out that patients rarely have pure vascular dementia or pure Alzheimer’s disease. Autopsy findings usually reveal evidence of both pathologies.

That begs the question, then, whether the vascular risk factors that directly lead to vascular dementia work additively with another pathology associated with production of the amyloid plaque deposits classically associated with Alzheimer’s disease or whether vascular risk factors somehow also contribute to the development of those plaques.

To find out, Gottesman and colleagues representing the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) - PET Amyloid Imaging Study prospectively followed 346 participants without dementia from communities in Washington County, MD; Forsyth County, NC; and Jackson, MI. They evaluated the participants for vascular risk factors and markers starting in 1987-1989, including body mass index ≥ 30, current smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and total cholesterol ≥ 200 mg/dL. They also measured amyloid deposition in the brain using florbetapir PET scans in 2011-2013. Florbetapir uptake was calculated as a standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs), and SUVR was considered “elevated” when it reached a value of 1.2.

Complete data on midlife vascular risk factors were available for 322 participants. Their mean age at the time of baseline assessment was 52 years, 58% were female, and 43% were black. Overall, 65 had no vascular risk factors, 123 had one risk factor, and 134 had two or more.

Amyloid SUVR was elevated in 164 patients (50.9%), which was observed when patients were a mean age of 76 years. Both elevated BMI and a higher number of vascular risk factors at midlife were associated with having an elevated SUVR at follow-up.

Independent Predictors of Elevated Amyloid SUVR

|

Risk Factors |

Adjusted OR (95% CI) |

|

BMI ≥ 30 |

2.06 (1.16-3.65) |

|

0 Midlife Vascular Risk Factors |

1 (reference) |

|

1 Midlife Vascular Risk Factor |

1.88 (0.95-3.73) |

|

≥ 2 Midlife Vascular Risk Factors |

2.88 (1.46-5.69) |

Of note, the presence of vascular risk factors in late life was not significantly linked with amyloid deposition.

More Reason for Early Intervention

According to Gottesman, “our study suggests that there is a direct association between these vascular risk factors, when measured in middle age, and brain amyloid, which is what is thought by leading hypotheses to cause Alzheimer's disease when it accumulates.”

For now, the underlying pathology driving the increased concentration of plaques associated with vascular risk factors, and whether it is the same as the pathology driving cardiovascular events, remains speculative. According to Gottesman, “it's possible that the impact on Alzheimer's disease risk is all through strokes or subclinical strokes, but our data suggest a specific effect of vascular risk factors on amyloid. One theory is that unhealthy vessels in the brain may adversely affect clearance of amyloid, or may inadequately clear other toxins that ultimately lead to more amyloid deposition.”

For the investigators, the clinical implications are clear. “Treat risk factors, and treat them in middle age,” Gottesdam recommended. “Our study obviously doesn't show that controlling these risk factors will reduce the risk of Alzheimer's, but this is the potential implication of the findings. Clinical trials testing various vascular risk factor treatments haven't shown a clear benefit in reducing Alzheimer's risk, but our study emphasizes that this may be because the studies aren't long enough.”

Questions remain specifically with regard to statin use. A mainstay of cardiovascular risk reduction, it is less clear if these agents offer neuroprotection as well, given that some—but not all—studies have linked them with poorer cognitive outcomes. Gottesman speculated that since patients are usually initiated on statins after developing high cholesterol and/or other vascular risk factors, it may be that these factors, not the statins themselves, confer the negative effects on cognitive function.

Sources

Gottesman RF, Schneider ALC, Zhou Y, et al. Association between midlife vascular risk factors and estimated brain amyloid deposition. JAMA. 2017;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Gottesman reports serving as associate editor for Neurology and receiving research support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Karen Meys

Karen Meys