Monkeypox and the Heart: Acute Myocarditis Rare, With Good Outlook

In this case report, a 31-year-old man had a mild and self-limiting disease course with a full recovery.

Researchers in Portugal successfully treated a case of acute myocarditis in a patient with monkeypox and say it should be on physicians’ radars as a rare, but potentially serious complication.

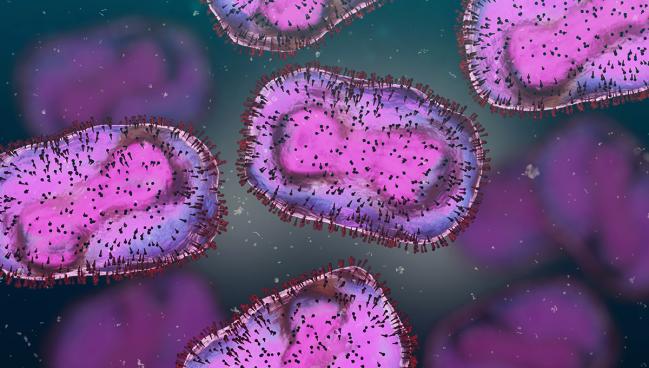

Monkeypox is a zoonotic orthopoxvirus similar to the variola virus, which causes smallpox. As of September 1, 2022, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported 19,465 total confirmed monkeypox/orthopoxvirus infections in the United States. Globally, there have been more than 52,000 confirmed cases, most in men who report having had sex with men.

Online today in JACC: Case Reports, a group led by Ana Isabel Pinho, MD (São João University Hospital Centre, Porto, Portugal), describe the case of a 31-year-old male who presented to the emergency department complaining of waking in the night with chest tightness radiating to his left arm. He had been diagnosed with monkeypox 3 days prior. The monkeypox infection was confirmed with a positive PCR assay of swabbed skin lesion, and the authors describe a thorough workup to get to the myocarditis diagnosis.

Overall, the patient required minimal management while hospitalized and made a full recovery.

“We believe that reporting this potential causal relationship can raise more awareness [among] the scientific community and health professionals for acute myocarditis as a possible complication associated with monkeypox and might be helpful for close monitoring of affected patients for further recognition of other complications in the future,” Pinho and colleagues conclude.

The authors add that virus-associated myocarditis and myopericarditis have been reported in a small portion of patients after receiving the smallpox vaccine in the years since it was introduced in the 1950s. “By extrapolation, the related monkeypox virus can have tropism for myocardium tissue or cause immune-mediated injury to the heart,” Pinho and colleagues note.

Mohammad Madjid, MD (David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles), who was not involved in the case, agreed. Noting the challenge of diagnosing myocarditis, he said the authors appropriately ruled out other causes.

“This is a well-written case report, and it is very clinically relevant,” he told TCTMD. “Many times, adequate workup is not done. That being said, we see myocarditis after many viral diseases . . . so the primary suspicion [often] comes after noticing temporal relations like a recent vaccine or infection. . . . And as we have seen, it is well documented in COVID.” Recently, a study of nearly 43 million people—one of the largest studies to date—confirmed once again that while myocarditis does occur in some patients after vaccination or SARS-CoV-2 infection, the risk of myocarditis is low and has a relatively benign disease course.

Largely Unremarkable Workup

According to Pinho and colleagues, the patient had no preexisting CV disease and his only current medication was pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV infection. He reported having a mild SARS-CoV-2 infection 2 months prior to the monkeypox diagnosis and no history of illicit drug use.

On examination, there were characteristic monkeypox skin vesicles and pustules on his face, wrists, thighs, and genitalia. He had no fever and was hemodynamically stable. Cardiopulmonary auscultation and the other physical examinations were unremarkable. Routine laboratory tests showed elevations of C-reactive protein (70 mg/L; normal < 3), creatine phosphokinase (291 U/L; normal 10-172), high-sensitivity troponin I (6,000 ng/L; normal < 34), and brain natriuretic peptide (155 pg/mL; normal < 100). Initial ECG revealed sinus rhythm with nonspecific ventricular repolarization abnormalities. On transthoracic echocardiogram, biventricular systolic function was preserved, with no pericardial effusion. Chest X-ray was normal for cardiothoracic index, with no interstitial infiltrates, pleural effusion, or masses.

The patient was admitted to the ICU under airway isolation and was clinically stable enough to undergo cardiac MRI within 24 hours of admission. That evaluation was “consistent with myocardial inflammation and the diagnosis of acute myocarditis was assumed by the presence of both major updated Lake Louise criteria,” the authors say. The group also ruled out HIV, herpes simplex virus, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C. They further performed serologies and PCR serum assays for the most common cardiotropic viruses, confirmed that thyroid function was normal, and screened for antinuclear antibodies and rheumatoid factor before reaching the myocarditis diagnosis.

Last week, an international collaborative group published a report in the New England Journal of Medicine on 528 patients diagnosed with monkeypox between April and June 2022. Only two cases of myocarditis were reported among them, making the new case report a unique addition to the literature.

According to Pinho and colleagues, their patient was treated with supportive care and exercise restriction and was discharged after 1 week. Following discharge, cardiac enzymes were within normal range, there was sustained electric and hemodynamic stability, and the skin lesions were healing.

Positive Outlook, With Some Cautions

Also commenting on the case for TCTMD, Leslie T. Cooper Jr, MD (Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL), said the patient’s mild disease course tracks with the experience of patients who develop myocarditis after smallpox vaccination.

“In that setting, it's also a mild disease with essentially an 87% rate of full recovery,” he said. Cooper added that the fact that this patient received no specific therapy reiterates the mild, self-limiting nature of myocarditis caused by an orthopoxvirus, and by monkeypox in particular.

“His young age may have been a factor in the relatively mild course, but it’s hard to know because as far as I know, there are only a handful of cases in the world,” he added.

Although the authors did not describe a long-term follow-up strategy for this patient, Cooper said performing a repeat cardiac MRI, or at a minimum an echocardiogram, at 6 months postdischarge to be sure that there is no clinical progression is likely a safe bet.

Madjid added that he would consider having a patient like this one wear a Holter monitor after discharge to allay concerns about rhythm abnormalities before approving a return to work or strenuous exercise.

Both Cooper and Madjid noted that although the authors did not do a biopsy, it did not appear to be clinically indicated for this patient. However, they said, it might be useful in a sicker and/or older patient presenting with myocarditis or myopericarditis in the setting of a monkeypox infection.

L.A. McKeown is a Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD, the Section Editor of CV Team Forum, and Senior Medical…

Read Full BioSources

Pinho AI, Braga M, Vasconcelos M, et al. Acute myocarditis – a new manifestation of monkeypox infection? JACC Case Rep. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Pinho, Cooper, and Madjid report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments