More Adverse Events, Higher Costs With Impella: New Observational Studies

Experts point to pitfalls in these kinds of data and say halting Impella use is not the answer—quality and patient selection are key.

PHILADELPHIA, PA—Two large observational studies are casting doubt on how well newer forms of mechanical circulatory support (MCS) are performing in real-world practice in the United States. The findings, released this morning at the American Heart Association 2019 Scientific Sessions, hint at more adverse events—including in-hospital death and major bleeding—as well as higher costs with the Impella percutaneous left ventricular assist device (Abiomed) versus an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP).

Clinicians who spoke with TCTMD said that the data must be interpreted with caution but that they speak to the need for better understanding of who should receive the device and when, with an eye toward reducing the variations in use and outcomes currently seen across US hospitals.

Amit Amin, MD (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO), and colleagues tracked trends in 48,306 patients undergoing PCI with MCS for a variety of indications at more than 400 hospitals between 2004 and 2016, outlining their findings in a paper simultaneously published in Circulation. Their numbers were derived from the Premier Healthcare Database.

The second study, presented by Sanket S. Dhruva, MD (San Francisco VA Medical Center/University of California, San Francisco), focused on acute MI patients with cardiogenic shock (AMICS) undergoing PCI. The researchers identified 28,304 matched patients from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR) for the period between October 2015 and December 2017.

Ranya Sweis, MD (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL), who was scheduled to discuss both studies following their main arena presentation, highlighted the parallels between the two data sets.

“It was very impressive to me when I received both of the studies to review, that the results are very similar,” she told TCTMD. “I think that is a strong impetus that we need to really do the actual studies to look at Impella.”

Speaking to the press, Amin stressed the observational nature of his group’s data: the numbers do not prove causation, nor do they argue against clinical use. That said, he continued, the signal indicating no benefit, and possible harm, cannot be ignored.

“Therefore, I think more data are needed to further understand [what’s going on],” he told TCTMD.

Manesh Patel, MD (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC), who moderated the media briefing, agreed that unknown confounders, especially when dealing with such sick patients, might explain these results. But in the numerous analyses performed by Amin et al, “we certainly see potential for hazard,” Patel said. “And when you see potential for hazard, that requires us to think about how to better identify patients that may benefit, whether that’s through other registries or ideally randomized trials. All of those, I think, would require us as an interventional community and as a clinical community to say, ‘We want to understand this better.’”

Impella has been on the market in the United States since 2008. In 2015, Impella 2.5 garnered premarket approval for use in high-risk PCI, and then in 2016, this approval was extended to acute MI and postcardiotomy cardiogenic shock for not only the Impella 2.5 but also its successors, the Impella CP, 5.0, and LD devices. Other indications have since followed.

Despite extensive observational data on Impella use, as well as RCT data specific to high-risk PCI, AMICS has proven to be more elusive. Debate continues over how best to study Impella in the setting of cardiogenic shock and what clinicians should do while awaiting results from the first large randomized trial on the topic, DanGer.

Premier Healthcare Data

In the study led by Amin, all patients received MCS, and for 9.9%, that device was Impella. That proportion grew to 31.9% in 2016. Impella was less frequently used in patients who were critically ill (with mechanical ventilation, cardiac arrest, or cardiogenic shock) than in those who were less sick, and this did not change over time.

Overall, there was more than sixfold variation in the likelihood a patient would receive Impella across the 432 hospitals studied. The occurrence of bleeding varied by more than 2.5-fold across hospitals, while death, acute kidney injury (AKI), and stroke each varied by approximately 1.5-fold.

The researchers divided the data into two time periods that they dubbed the Impella era (2008-2016) and the pre-Impella era (2004-2007). Both adverse outcomes and hospital costs increased in the latter period; of note, costs rose in PCI patients with MCS but decreased in those without MCS.

Hospital stays were, on average, “shorter by about a day in the Impella arm as compared to the balloon-pump arm, despite which the incremental costs were about $15,000 more with Impella,” Amin said.

The investigators also performed propensity-score adjustment and used measures to account for differences in the hospitals where patients were admitted. Here, Impella use was associated with greater risks of death (OR 1.24; 95% CI 1.13-1.36), bleeding (OR 1.10; 95% CI 1.00-1.21), and stroke (OR 1.34; 95% CI 1.18-1.53), as well as a nonsignificant trend toward more AKI (OR 1.08; 95% CI 1.00-1.17).

Contacted for comment, Abiomed’s chief medical officer, Seth Bilazarian, MD, objected to what he sees as multiple flaws in the Circulation paper. “This observational, non-FDA-audited analysis is fundamentally flawed because it is based on poor quality, retrospective, payer coding data that lumps all indications together and is impossible to properly propensity match. In this data set, a patient walking in for an elective procedure looks the same as a patient in cardiac arrest with cardiogenic shock,” he told TCTMD via email.

Bilazarian also underlined the fact that Impella patients in this analysis were sicker at baseline, and the data set overall lacks information on the degree of shock and metabolic derangement, the rate of surgical turndown, and the timing of Impella use. Importantly, it “removed patients who were escalated to other therapies, which is the major driver of costs and poor outcomes for IABP,” added.

Moreover, Bilazarian said, these findings are in contrast to prior peer-reviewed and real-world studies showing more favorable outcomes and better cost-effectiveness with Impella.

Senior author Sunil Rao, MD (Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC), offered a different perspective: that signals seen in large, observational analyses of Impella have been largely consistent. “Now, people have overinterpreted them to say, ‘Maybe we should have a moratorium on Impella use.’ I don’t think that’s the case,” he cautioned TCTMD. “I do think, though, that there’s some circumspection required when you’re putting in these huge devices, because there is the potential for risk.”

Discrepancies in use among critically ill versus less-sick patients at the hospital level may be what’s behind the variation in use and outcomes, Rao indicated, stressing that these devices should be reserved for the situations of greatest need.

Amin, in his presentation, acknowledged several of the limitations mentioned by Bilazarian. For example, diagnosis was based on ICD-9 codes and some clinical details were unavailable. In addition, the reason for Impella use could not be pinpointed. Even so, he asserted, “these data underscore the need for defining the appropriate use of MCS in patients undergoing PCI.”

NCDR Analysis

Dhruva, in his presentation of NCDR data, described how Impella use rose from 3.5% to 8.7% in AMICS patients between the end of 2015 and the end of 2017.

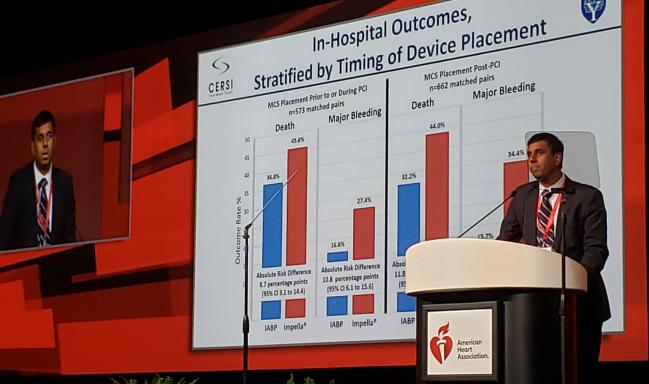

Using their initial cohort of more than 28,000 individuals, the researchers identified 1,680 propensity-matched pairs who received Impella versus IABP. In-hospital mortality was 45.0% with Impella and 34.1% with IABP. Major bleeding affected 31.3% and 16.0% of the Impella and IABP patients, respectively.

These differences were more severe in patients who received MCS after PCI, but they were still apparent in cases where MCS use occurred before or during PCI.

Propensity-Matched AMICS Patients: In-Hospital Outcomes

|

|

Impella |

IABP |

|

MCS After PCI Death Major Bleeding |

44.0% 34.4% |

32.2% 15.7% |

|

MCS Before/During PCI Death Major Bleeding |

45.6% 27.4% |

36.8% 16.6% |

“These data provide important insights into the performance of MCS devices in routine clinical practice, and outcomes in RCT settings may differ,” Dhruva concluded. “Better evidence and guidance are needed regarding the optimal management of patients with AMICS as well as the role of MCS devices in general, and Impella in particular.”

Ajay Kirtane, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY), told TCTMD he found the stratified analysis of outcomes based on MCS timing particularly compelling. “Sometimes it’s unclear, for instance in the other analysis, whether the device is placed after a complication or something else that occurred, and that alone would predispose patients to a bad outcome,” he observed.

What’s most important to recognize, however, “is there are so little randomized data in this entire space, not just with this device but with any device,” he said. While some might see this as an argument to use extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) instead, that takeaway doesn’t make sense, given that there isn’t much evidence for ECMO either. “So it really stresses the need to try to do some randomized trials,” Kirtane said.

Asked whether people should, based on today’s studies, be more thoughtful about Impella use, Kirtane advised: “We should always be circumspect with the use of any mechanical circulatory support device, because they [require] large-bore access and there are downsides. This underscores the need to think about every case and assess specifically why we’re putting the device in. That’s what we try to do in practice, because we know that everything has a risk associated with it.”

Is It Impella or Something Else Entirely?

Ankur Kalra, MD (Cleveland Clinic, OH), whose own research has tracked MCS trends in more than 400,000 patients from 2012 to 2015, said the findings are intuitive. He’s seen firsthand “a lot of variability in use and in the quality in which these devices are being utilized.”

Much of the issue is that “we haven’t really defined the right patient populations in whom the device should not be used. I think that will have to be done if this is to mature into a cornerstone therapy for patients who need the device for cardiogenic shock, even for high-risk PCI,” he explained.

Based on these two studies, “it’s not unreasonable to take a pause and look the data more carefully and look at the dissemination of the device, and [to] really ask ourselves what’s happening,” Kalra commented. “I want something to work, I want the device to work. If it works, it’s a win for everyone. But I think something is just not matching up.”

The National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative (NCSI) experience shows a “system-wide, well-executed, multidisciplinary strategy is a good strategy,” Kalra said. “Maybe there’s a lot more in the process than in the device. So far, that’s been the take home for me in my practice.”

Rao agreed programs like the NCSI might be a solution. Yet he reminded TCTMD that when putting results in context, it’s important to think of the denominator. Here, his research team included both patients who received Impella and those who did not. A recent look at NCSI outcomes, as covered by TCTMD, made the case for a strategy emphasizing early, aggressive treatment of AMICS, but that analysis only included patients receiving MCS.

As to how to gel the current results with the markedly better survival obtained by the NCSI, Rao said it’s “hard to draw parallels between the two.”

His suspicion, he added, is that the NCSI’s success is “driven by the fact that these are expert centers, that they have some kind of organized approach to shock that includes mechanical support.” These efforts, though, might guide the field in ascertaining how to use Impella appropriately, Rao suggested. “The way they are currently being used, it certainly seems there is association with adverse outcomes.”

Exactly what’s driving Impella use can’t be known from the Premier database, he acknowledged. “My sense is interventional cardiologists want to do the right thing. They want to get good outcomes. They’re faced with really sick people, and they want to do everything they can to make sure the patient does well. So the challenge is, when you’re working in this data-free zone, you sort of rely on your best clinical judgment and that judgment drives you to use these devices.”

To TCTMD, Amin commented that it’s difficult to know what ingredients of the NCSI are making the most impact on survival. Measures to reduce bleeding and AKI might be accompanied by other effects surrounding that intervention that also play into the ultimate outcome.

Both Amin and Sweis, the scheduled discussant, said the hospital-level inconsistencies merit close attention.

In the end, today’s late-breaking session ran late and Sweis’ presentation was abruptly dropped from the program. Speaking with TCTMD, she said, “I can’t come up with a feeling for why Impella itself or the use of Impella in the patients that need it would cause them to have worse outcomes, so I have to think it’s related to some of the things like bleeding and [its effects] on mortality, which is well demonstrated even in smaller sheath sizes for PCI.”

Rather than dissuading Impella use, Sweis concluded, what these results show is that there are ways to improve the procedure now while awaiting more data.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Amin AP, Spertus JA, Curtis JP, et al. The evolving landscape of Impella use in the United States among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with mechanical circulatory support. Circulation. 2019;Epub ahead of print.

Dhruva SS. Utilization and outcomes of Impella vs IABP among patients with AMI complicated by cardiogenic shock undergoing PCI. Presented at: AHA 2019. November 17, 2019. Philadelphia, PA.

Disclosures

- Amin reports receiving a comparative-effectiveness research KM1 career development award from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences and the National Cancer Institute, receiving an unrestricted grant from MedAxiom Synergistic Healthcare Solutions, and serving as a consultant to Terumo and GE Healthcare.

- Rao, Sweis, and Kalra report no relevant conflicts of interest.

- The study led by Dhruva was supported in part by a Center of Excellence in Regulatory Science and Innovation (CERSI) grant to Yale University and Mayo Clinic from the US Food and Drug Administration. It also was supported by the American College of Cardiology’s National Cardiovascular Data Registry.

- Patel reports serving on the advisory boards of Bayer, Janssen, Mytonomy, and Procyrion as well as receiving research grants from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen, Procyrion, and HeartFlow.

- Kirtane reports receiving institutional funding to Columbia University and/or the Cardiovascular Research Foundation from Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, CSI, Philips, and ReCor Medical.

- Bilazarian is chief medical officer of Abiomed.

Comments