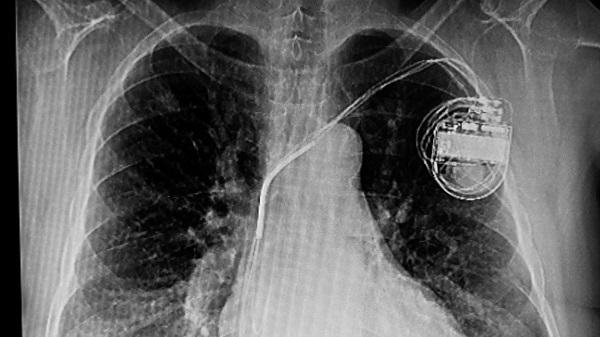

Most Infected Cardiac Implanted Electronic Devices Not Removed Fast Enough

Getting the infected device out within 30 days is associated with better survival, but just one in five were taken out on time.

WASHINGTON, DC—The vast majority of patients who develop an infection related to a cardiac implanted electronic device (CIED) do not have the hardware extracted in a timely manner, and these patients are at a significantly higher risk of death in follow-up, according to the results of a new Medicare analysis.

Device extraction and lead removal within 30 days, which is recommended by all the major societies, is associated with a 27% lower risk of death at 1 year when compared with not having the device removed. Prompter removal is associated with an even lower risk of death, report investigators.

“We’ve identified a large gap in care among patients with pacemaker and defibrillator infections,” said lead investigator Sean Pokorney, MD, MBA (Duke Health/Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC), during a featured clinical research session at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2022 Scientific Session. “I want to close that gap to save lives.”

To TCTMD, Pokorney said the reasons for delays in removing an infected device are multifactorial, noting that it can take time between the initial infection diagnosis and the realization that the hardware needs to be extracted.

“Part of that is, especially the way healthcare is structured, because so many of these patients are on internal medicine or hospitalist services,” he said. “They don’t come in for a cardiology-related reason. They come in with systemic infections and they’re not complaining about the device, but saying they feel fatigued, run down, or maybe they have a fever. They get put on an internal medicine service where they’re diagnosed with a bloodstream infection, but it takes some time for them to realize we need to talk to cardiology and maybe the device needs to come out.”

Rachel Lampert, MD (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT), who commented on the study during the ACC session, said that the extraction of infected devices has been recommended by professional societies for many years, “just based on infection recurrence and what people felt was common sense.” The addition of data now showing higher rates of death among those who don’t have the device removed now backs up those recommendations, she said.

Just One in Five CIEDs Extracted Within 30 Days

Infections with CIEDs is common in clinical practice, with one study reporting that the overall rate is 6.2% at 15 years and 11.7% at 25 years. If the hardware is completely removed, the risk of infection relapse is very low, somewhere in the range of 1% or less, said Pokorney. However, if the device is only partially removed, or the patient is treated with antibiotics alone, infection relapse rates range from 50% to 100%.

“We know that managing CIED infections is going to be an ongoing challenge for us as our patients are living longer based on advancements in heart failure therapy,” said Pokorney.

Complete device and lead removal is a class I indication for all patients with definite CIED system infection. The American Heart Association and Heart Rhythm Society, as well as other major European groups including the European Heart Rhythm Association, all recommend device and lead removal, with complete and prompt extraction advised.

Even with the strength and uniformity of those recommendations, the researchers were concerned about adherence to the guidelines. With this in mind, they turned to a Medicare database of fee-for-service patients implanted with a de novo CIED between 2006 and 2019. Cases of endocarditis or infections of an implanted device, both of which required documented antibiotic therapy started within 30 days after the infection, were collected and analyzed.

I want to close that gap to save lives. Sean Pokorney

In total, 1,065,549 devices were implanted, and patients were followed for a median of 4.6 years. There were 11,619 (1.1%) infections of these implants, occurring at a mean of 3.7 years after implantation. Those who developed an infection tended to have more comorbidities, including dementia, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, renal disease, and prior stroke/transient ischemic attack. For those who developed an infection, 14.7% had received a Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) device, 56.8% a pacemaker, and 28.5% an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

By 30 days, 9,510 patients with infections, or 81.8%, did not have the CIED extracted, and the mortality rate at 1 year was 32.4% for this group.

Those who had the infected hardware removed in the first 30 days had a significantly lower risk of death at 1 year compared with those who didn’t have the device extracted (adjusted HR 0.73; 95% CI 0.70-0.81). Looking specifically at early extraction, those who had the infected CIED removed within 6 days had a 41% lower risk of death compared with patients who didn’t have the device extracted within the first 30 days (P < 0.001).

To TCTMD, Pokorney said the low rate of extraction within 30 days was surprising, and while they anticipated a treatment gap, they hadn’t expected just one in five to be treated according to society guidelines. “It highlights that this is such a large problem, really a public health crisis within the country for our patients with devices,” he said.

During the ACC session, Lampert said she was also taken aback by the very low rate of device extraction. She added that caution is warranted when analyzing Medicare data, though, noting there is the potential for confounding, because it might be that sicker patients are not undergoing extraction because physicians are concerned about their risk. Pokorney acknowledged the potential for unmeasured confounding variables with retrospective databases, noting they are working on several sensitivity analyses, including those using falsification endpoints, that they hope to include when the study is published.

Institutional Responses to Problem

In addition to physicians failing to recognize that the hardware needs to be taken out, Pokorney said there can be operational challenges, too. Device and lead removal in the hands of experienced operators can be safely performed, but it does need to be done in a hybrid operating room, often requiring the presence of cardiac surgery. Imaging is often required so that physicians understand where the leads are located.

“That takes some time to set up and get everything coordinated,” said Pokorney. “That’s why these data are so important. Once you can highlight to hospitals, health systems, and providers that early extraction provides such a benefit, we can start focusing on how to break down those barriers.”

The Duke Clinical Research Institute is currently involved in a demonstration project at three US centers to increase guideline-driven care for patients with definitive or suspected CIED infection. The quality-improvement program will focus on how to assemble an interdisciplinary team to address gaps in care for recognizing and treating CIED infection. It also involves developing institutional care pathways so that patients are identified early in order to facilitate device removal as quickly as possible.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Pokorney SD, Zepel L, Greiner MA, et al. Low rates of guideline-directed care associated with higher mortality among patients with cardiac implanted electronic device infection. Presented at: ACC 2022. April 3, 2022. Washington, DC.

Disclosures

- Pokorney reports no conflicts of interest.

Comments