OPTION: LAAO Matches Up to DOACs After Ablation, but Questions Remain

Although some of the trial’s methodology was critiqued, the results provide fodder for shared decision-making discussions.

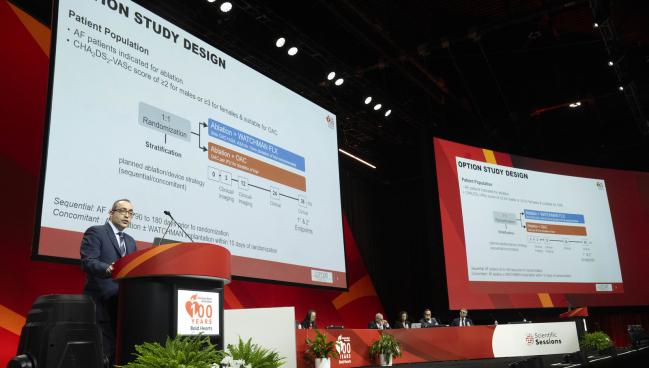

Photo Credit: American Heart Association

Left atrial appendage occlusion (LAAO) appears to be a viable alternative to oral anticoagulation for stroke prevention in select patients undergoing catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation (AF), the OPTION trial shows.

LAAO—performed with the Watchman FLX device (Boston Scientific) at the same time as ablation or in a sequential manner—lowered the risk of bleeding while providing noninferior efficacy in terms of the risk of all-cause death, stroke, or systemic embolism through 3 years of follow-up, Oussama Wazni, MD (Cleveland Clinic, OH), reported at the American Heart Association 2024 Scientific Sessions in Chicago, IL, over the weekend.

The message from the trial is that “in an ablation population with a CHA2DS2-VASc score of at least 2 in men and at least 3 in women, it is reasonable to consider left atrial appendage closure,” Wazni told TCTMD, “instead of continued oral anticoagulation.”

Importantly, the trial was not a comparison of Watchman versus oral anticoagulation in an all-comers AF population, but addressed a specific and important clinical question, said Wazni, which is what to do about anticoagulation after AF ablation. Some patients will stop taking their blood thinners thinking that the stroke risk associated with AF has been eliminated by the procedure. Others, he added, may develop silent AF, and guidelines state that anticoagulation should be continued even after ablation, a strategy that carries a risk of major bleeding.

“So we thought: okay, can we mitigate all of this by closing the appendage with a Watchman FLX device?” Wazni said.

The findings were published simultaneously online in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Weighing OPTION

Not everybody was swayed by the trial results, with some raising questions about the inclusion of all-cause death—an outcome unlikely to differ between the LAAO and anticoagulation arms—in the composite primary endpoint for efficacy (assessed for noninferiority) and about the types of bleeding included in the composite primary endpoint for safety (assessed for superiority).

“On the surface, the device finally appears to win the elusive bragging rights. Technically, it is a win for LAA closure, as the prespecified criterion for a win was met—ie, noninferiority for efficacy and superiority for safety was met,” Sanjay Kaul, MD (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA), told TCTMD.

“However, on deep dive, superiority for safety was met using an endpoint that was arguably biased in favor of the device as it excluded procedural bleeding. Had they used procedural bleeding, superiority would not be met, and the win criterion would not have been satisfied,” he said, adding that “there was lot of missing data that was not accounted for in the primary analysis.”

Taken together, Kaul commented, “while enthusiasts of the device will celebrate the win, the overall results are not very convincing.”

Manesh Patel, MD (Duke University, Durham, NC), the discussant for the trial, agreed that OPTION is not a home run for LAAO in this setting. Speaking with TCTMD, he explained that as a general principle, noninferiority trials should avoid endpoints that bias the results toward establishing noninferiority. Prior trials of LAAO have used composite endpoints that included stroke, systemic embolism, and mortality (either all-cause or cardiovascular), he said, but when including mortality, which occurred much more frequently than stroke in OPTION, “it does bias you towards finding noninferiority.”

Some might debate, too, whether the 5% noninferiority margin used in the trial was too large, he indicated.

Another issue, however, emerges when looking at the low overall stroke rates in this population, regardless of which treatment they received, Patel said, pointing out that higher-risk patients—such as those with heart failure or an LVEF less than 30%—were excluded. The rate of ischemic stroke, too, was very low in both groups—1.2% in the LAAO arm and 1.3% in the anticoagulation arm.

“A bigger question might be if these patients need anticoagulation or Watchman at all because the event rates are so infrequent that one might say you need to better risk-stratify who needs the therapy,” he said. “I’m not suggesting [LAAO is] not a potentially effective option, but it should be considered in patients who are at significant risk.”

By enrolling a lower-risk population with low event rates, “you’re likely to find noninferiority, but the real question is: is it informative?” Patel said. “I’m not sure that it’s informative because those patients may not be ones that you would potentially consider. We should be considering what is the risk of stroke for those patients if you’re treating them at all.”

While enthusiasts of the device will celebrate the win, the overall results are not very convincing. Sanjay Kaul

David Cohen, MD (Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY, and St. Francis Hospital, Roslyn, NY), commented to TCTMD that these methodological and statistical concerns are legitimate. He added, however, that they “relate to issues that come up with almost every noninferiority trial.”

What’s important is that the investigators provided the results in a variety of different ways, he said.

“I’m frankly less concerned about which was tested for superiority, which was tested for noninferiority,” Cohen said. “The results in both cases seemed reasonably reassuring. While people can quibble with specific assumptions and the exact nature of the statistical tests that were prespecified, at the end of the day, we have a very good, rigorous clinical trial with a decent number of patients in it that provides information that clinicians can use to make decisions with their patients. And that’s what we really want. We want high-quality data that can be used to inform decisions.”

Stroke Prevention After Ablation

Following AF ablation, guidelines recommend continuing oral anticoagulation for patients with a moderate or high risk for stroke. Still, some patients might wish to stop taking the medication due to cost or bleeding risks, with studies showing about one-quarter of such patients will discontinue anticoagulation within a year.

The OPTION trial was designed to test whether LAAO can provide the same level of stroke protection, while lowering bleeding risks, after ablation. The study was conducted at 106 sites in 10 countries, with investigators enrolling 1,600 patients (mean age 69.6 years; 34.1% women), who were undergoing catheter ablation for AF and who had an elevated CHA2DS2-VASc score (at least 2 for men and 3 for women)—the mean score was 3.5 overall. Participants were randomized to continuing oral anticoagulation or to LAAO performed either at the same time as ablation or sequentially—about 60% of procedures were performed 90 to 180 days after ablation and 40% were performed within 10 days of ablation.

A direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) was used in 95% of patients in the medical therapy arm of the trial, with the most common agents being apixaban (59.3%) and rivaroxaban (27.2%).

In the LAAO arm, implantation of the device was successful in 98.8% of cases, with a complete seal of the appendage seen in 81.0% of patients at 3 months and 79.7% at 1 year. The incidence of device-related thrombus was 1.9% at 1 year. Overall, 22 patients (2.8%) had serious adverse events related to the device or procedure—those included four cases of bleeding, three arrhythmias, three pericardial effusions, and three pseudoaneurysms.

At the end of the day, we have a very good, rigorous clinical trial with a decent number of patients in it that provides information that clinicians can use to make decisions with their patients. David Cohen

The primary efficacy endpoint, assessed for noninferiority with a 5% margin, was a composite of all-cause death, stroke, or systemic embolism. At 3 years, the rate was 5.3% in the LAAO arm and 5.8% in the anticoagulation arm (HR 0.91; 95% CI 0.59-1.39), a difference that established the noninferiority of LAAO (P < 0.001).

The rate of all-cause death was numerically lower in the LAAO group (3.8% vs 4.5%), with low rates of ischemic stroke (1.2% with LAAO vs 1.3% with anticoagulation), hemorrhagic stroke (0.4% in each group), and systemic embolism (0.3% with LAAO vs 0.1% with anticoagulation) recorded.

The primary safety endpoint, assessed for superiority, was a composite of non-procedure-related major bleeding or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. Through 3 years, there was a significantly lower rate in the LAAO arm (8.5% vs 18.1%; HR 0.44; 95% CI 0.33-0.59). ISTH major bleeding, including procedure-related bleeding, was a secondary endpoint, occurring in 3.9% of LAAO-treated patients and 5.0% of those on oral anticoagulation, a difference that met criteria for noninferiority (P < 0.001) but not superiority.

Building an Evidence Base

Nazem Akoum, MD (University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle), a member of the American College of Cardiology’s Electrophysiology Council, said that OPTION helps answer questions about how to manage patients after AF ablation and about the residual risk of stroke, which was lower than anticipated.

Bleeding rates also were lower than expected, Akoum noted to TCTMD, which “may speak to increased expertise with the device and the protocol that was used for anticoagulation.”

Asked whether the trial is large enough to be definitive, he responded: “This is one study, obviously. . . . To build an evidence base, you have to have consistent results. So other studies with a similar design, maybe with a different left atrial appendage occlusion option, that would reproduce similar results would definitely help build that database.”

For now, OPTION is “going to help clinicians counsel patients about all of these possible scenarios, including the ability to concomitantly do ablation and do a left atrial appendage occlusion and possibly reduce the risk associated with multiple procedures by consolidating them all into one,” Akoum said. “It helps also compare in a postablation patient population the bleeding risk associated with a DOAC compared to left atrial appendage occlusion.”

But there are still some questions that need to be answered, he said, citing the need for more information about the initial ablation’s impact on AF burden in both trial arms and how that influenced stroke rates, and about how arrhythmia recurrences were handled in terms of use of anticoagulation and repeat procedures.

“It’s very encouraging to see these data, but hopefully with other studies confirming and growing that evidence base we’ll be able to answer all of these questions,” Akoum said.

For now, OPTION does not represent a “slam dunk for LAAO,” Cohen said. “It didn’t win on all criteria. It’s not superior in every respect to oral anticoagulation. And continuing oral anticoagulation is a perfectly reasonable option as well. But I think this should allow patients and clinicians to have an informed discussion about the trade-offs, the risks, the benefits, what is known, and what is not.”

Wazni appeared to agree. “This is something that should be based on a shared decision-making dialogue or discussion with the patients,” he said. “I’m not saying everybody has to stop anticoagulation and get a Watchman FLX device. What we are saying here is now patients have this data and based on it they can decide whether to continue taking oral anticoagulation or have the device instead.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Wazni OM, Saliba WI, Nair DG, et al. Left atrial appendage closure after ablation for atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2024;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- OPTION was funded by Boston Scientific.

- Wazni reports consulting and/or speaking for Biosense Webster, Boston Scientific, and Medtronic.

- Patel reports receiving research support from Bayer, AstraZeneca, Novartis, HeartFlow, Janssen, Idorsia, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and consulting or serving on advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Janssen, Idorsia, and Novartis.

- Cohen reports receiving research grant support and consulting income from Boston Scientific.

Comments