PACMAN-AMI: Positive Plaque Changes With Early Alirocumab Use in Acute MI

The trial is important in helping to understand how lipid-lowering therapy improves outcomes, Michael Blaha says.

WASHINGTON, DC—Adding the PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab (Praluent; Sanofi/Regeneron) to high-intensity statin therapy enhances coronary plaque regression and stabilization when started early after an acute MI, the PACMAN-AMI shows.

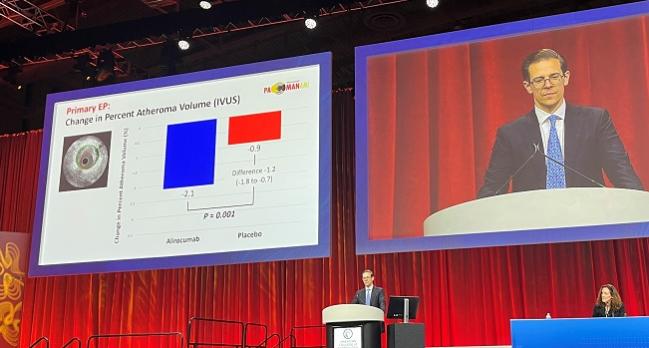

Serial intracoronary imaging showed that the combination provided greater reductions in percent atheroma volume and lipid burden, as well as a greater increase in minimal fibrous cap thickness, through a year of treatment compared with statin therapy alone, Lorenz Räber, MD, PhD (Bern University Hospital, Switzerland), reported here at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2022 Scientific Session.

The findings, published simultaneously online in JAMA, “provide the mechanistic rationale in favor of an early initiation of very intensive LDL-lowering in acute MI patients,” he concluded.

Commenting after Räber’s presentation, Michael Blaha, MD (Johns Hopkins University Medical Center, Baltimore, MD), said the PACMAN-AMI results are relevant for a couple of reasons even though alirocumab has already been shown to have a clinical benefit in ODYSSEY OUTCOMES, which demonstrated a reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events with the PCSK9 inhibitor in stabilized patients with ACS.

First, “it’s extremely important to understand the mechanism of what we’re doing and how that’s influencing outcomes,” Blaha said, adding that the information will prove useful when speaking with patients about plaque modulation. “I also think it’s important to understand the biology of lipid-lowering therapy.”

And second, Blaha said, the trial is important because of the targeted population, with lipid-lowering therapy being initiated earlier shortly after an acute MI, building on several prior studies supporting the safety of treatment in this setting.

“Those things I think make this study extremely relevant in 2022,” he said.

In PACMAN-AMI, there were no differences between trial arms in all-cause mortality and MI, but there was a significant reduction in ischemia-driven coronary revascularization of non-infarct-related arteries with alirocumab treatment (8.2% vs 18.5%).

Asked whether a more-definite study of clinical outcomes would be needed before moving PCSK9 inhibition earlier after acute MI, Blaha noted that a single-center study of another agent in this class—evolocumab (Repatha; Amgen)—showed that in-hospital administration during large MIs appeared safe and effective. That’s bolstered, he said, by the results of HUYGENS with evolocumab and now PACMAN-AMI with alirocumab.

There are “a lot of data now coming out that shows that this is a viable strategy that appears safe,” Blaha told TCTMD. “I think selectively we can start doing this even now. I think it’s safe to do it. I think there’s mechanistic reasons to think we should do it.”

Still, a more-definitive trial would be helpful, he said, pointing out that a trial of evolocumab in acute MI was recently announced. “I think selectively we can start it now, but probably for wide guideline endorsement, we need the trial.”

PACMAN-AMI

Coronary plaques that are likely to rupture and cause an acute MI often have a large plaque burden, high lipid content, and thin fibrous caps, Räber noted. Statins slow the progression of coronary atherosclerosis, but the impact of PCSK9 inhibitors on plaque characteristics, especially when given early after ACS, is not well known.

PACMAN-AMI, conducted at nine study sites in Switzerland, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Austria, was designed to study that question. Investigators enrolled 300 patients (mean age 58.5 years; 18.7% women) with acute STEMI (53%) or NSTEMI (47%) who underwent successful PCI of the infarct vessel and had angiographic evidence of nonobstructive atherosclerosis (20% to 50% diameter stenosis) in two non-infarct-related arteries. LDL-cholesterol level had to be above 125 mg/dL (3.2 mmol/L) in statin-naive patients and above 70 mg/dL (1.8 mmol/L) in statin-treated patients. Only about 12% of patients were on statins when entering the study.

At baseline, patients had coronary plaque characteristics in the non-infarct-related arteries assessed using IVUS, near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), and optical coherence tomography (OCT). The imaging was repeated at 1 year.

After baseline imaging, patients were randomized to alirocumab 150 mg delivered subcutaneously every 2 weeks plus rosuvastatin 20 mg or placebo plus rosuvastatin. Treatment was started within 24 hours of successful PCI.

Through 1 year, LDL cholesterol dropped by an average of 50.7% in the placebo group and 84.8% in the alirocumab group.

That translated into a significantly greater reduction in IVUS-derived percent atheroma volume—the primary endpoint—in the alirocumab arm (2.13% vs 0.92%; P < 0.001).

One has to be impressed that if you get more than a 50% reduction [in LDL] you get more plaque remodeling. Anthony DeMaria

Two powered secondary endpoints also favored the addition of PCSK9 inhibition, with a greater reduction in the NIRS-measured maximum lipid-core burden index within 4 mm (79.42 vs 37.60; P = 0.006) and a larger increase in OCT-measured minimal fibrous cap thickness (62.67 vs 33.19 µm; P = 0.001).

Of note, all of these changes were greatest in patients with lower on-treatment LDL-cholesterol levels, particularly when they fell below 50 mg/dL. That, Räber said during a press briefing, suggests “that we should achieve very, very low LDL levels in our patients at very high risk.”

Blaha called the observed plaque changes, particularly those involving phenotype changes, “very impressive” and “pretty substantial,” pointing out that the findings are consistent with those of the HUYGENS trial with evolocumab. “It really shows a very consistent biology here, which is that further LDL-lowering in this acute period markedly modulates plaque,” he told TCTMD.

And it appears to be safe, as rates of adverse events (71% with alirocumab and 73% with placebo) and serious adverse events (32% and 33%) were similar in the two trial arms. The only adverse event of special interest that was significantly higher in the alirocumab-treated patients was the occurrence of general allergic reactions (3.4% vs 0).

Talking to Patients

Räber and others indicated that the findings of PACMAN-AMI could be useful when counseling patients with atherosclerosis.

Anthony DeMaria, MD (UC San Diego Health, La Jolla, CA), a past president of the ACC, said his patients often ask him how they can make their plaques go away. This trial, which DeMaria called the trial a “tour de force” during the press briefing, provides evidence that plaques can be remodeled even if they might not get much smaller. “I think that will incentivize patients in large measure,” he said.

The results also raise questions about whether there should be a goal below which LDL-cholesterol levels should be driven, DeMaria said, noting that there has been some debate about this in recent years. “Here, one has to be impressed that if you get more than a 50% reduction . . . you get more plaque remodeling,” he commented. “And if it can’t be done with statins alone then it should be done with statins plus whatever is necessary. So in my mind, I want my own LDL to be as low as possible.”

We’re changing your plaque, we’re stabilizing your plaque. We’re also regressing it a little bit, but that might be a small part of what we’re doing. Michael Blaha

Räber agreed that these data could be used in discussions with patients, saying that motivation is an important component when it comes to LDL-lowering therapy. Visualization of plaque changes is an additional piece of information that can keep patients on their medications, something that has proven to be a challenge for some.

The message Blaha tells patients is: “We’re changing your plaque, we’re stabilizing your plaque. We’re also regressing it a little bit, but that might be a small part of what we’re doing.”

The findings of PACMAN-AMI and other studies increasingly support the idea of getting PCSK9 inhibitors on hospital formularies to allow for earlier access to the medications for patients, Blaha added. That would ultimately improve access to the drugs, which has been getting better in recent years as costs have come down by about 50%.

These data also suggest that clinicians should be looking to stabilize coronary plaques earlier in the disease course, even before an MI has occurred. “It takes me to that future goal,” Blaha said.

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Räber L, Ueki Y, Otsuka T, et al. Effect of alirocumab added to high-intensity statin therapy on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the PACMAN-AMI randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The study was funded by Sanofi, Regeneron, and Infraredx. Regeneron provided alirocumab and placebo free of charge.

- Räber reports receiving grants from Sanofi, Regeneron, and Infraredx to Inselspital and speaker fees from Sanofi during the conduct of the study, as well as grants from Abbott, HeartFlow, Boston Scientific, and Biotronik to Inselspital and grants from Abbott, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Occlutech, Sanofi, Canon, and Medtronic for speaker and consultation fees outside the submitted work.

- Blaha reports consultant fees/honoraria from 89Bio, Akcea, Amgen, Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals, Inozyme, Kaleido, Kowa, MedImmune, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, and Siemens, as well as research grants from Amgen and Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals.

Comments