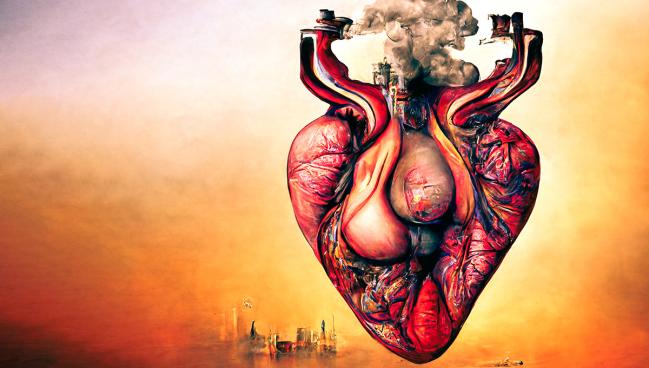

Pollution Deserves More Attention in Cardiology—and More Action

The adverse cardiovascular effects of pollution are greater than that of many other established risk factors, Jason Kovacic argues.

There’s plenty of evidence linking pollution with adverse cardiovascular outcomes, and the problem deserves to be better recognized and addressed by the cardiology community, argue the authors of two review papers published Monday.

“The burden here is alarming and I think that's really important to drive home,” senior author Jason C. Kovacic, MD, PhD (Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute, Darlinghurst, Australia), told TCTMD. “Pollution in all its forms is a greater health threat than that of war, terrorism, malaria, HIV, tuberculosis, drugs, and alcohol combined. The scale of the problem is absolutely alarming.”

Pointing to a recent paper published in the New England Journal of Medicine regarding the adverse cardiovascular effects of microplastics in carotid artery plaque as one example, Kovacic said that “the problem is not just coming, it's here. And we need to do so much to raise awareness and to act.”

While the scope of the issue can seem daunting, the best place for the cardiology community to start would be to recognize that this is “not a niche interest,” lead author Mark Miller, PhD (University of Edinburgh, Scotland), told TCTMD. Frustratingly, he said, even though the evidence has existed for a while connecting pollution and heart disease, “I think [for] a lot of cardiologists, it's perhaps not their focus. . . . In cardiology, we're still thinking of high blood pressure. We're still thinking about a diet and lack of physical exercise.”

Those are all “hugely important,” he continued, but air pollution, specifically, has now been ranked higher than smoking and hypertension as a cardiovascular disease risk factor by the Global Burden of Disease Study. “It's time to take this seriously,” he said. “It's time to start doing something about it. Yes, it's perhaps big policies that we need to try and tackle this. But the cardiologist can do something as well.”

For instance, he said, he’d like to see more training in medical school regarding the effects of air pollution. Additionally, Miller said cardiologists are “great advocates for change,” not only for their patients, but within society and government as well.

There's so much evidence accumulating that at some point it will no longer be acceptable to sit on the sidelines. Dhruv Kazi

Dhruv Kazi, MD (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center/Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA), who commented on the papers for TCTMD, agreed. “We haven't traditionally thought about the tight connection between climate change and cardiovascular health,” he said. “And now what we're seeing is both increasing awareness of that relationship—a clarification that we need to understand that relationship better—and certainly a resulting call to action. This isn't a distant threat, but it's here and now.”

Looking at All Pollutants

In two papers, published today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Miller, Kovacic, and colleagues do a deep dive into the research connecting cardiovascular disease with global warming, air pollution, and wildfires, and into the cardiovascular impact of water, soil, noise, and light pollution, respectively.

For the first, the authors call out specific examples of cardiovascular risk factors or events exacerbated by heat events (dehydration, sympathetic activation, increased cardiac strain, increased renal strain, peripheral vasodilation, increased coagulation, and heat stroke), air pollution (systemic inflammation, autonomic imbalance, endothelial dysfunction, increased blood pressure, platelet activation and increased coagulation, and impaired fibrinolysis), and wildfires (systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, impaired cardiac function, and reduced pulmonary blood flow).

The second paper explores perhaps lesser-known pollutants related to water, soil, noise, and light. They highlight the potential negative effects of toxic metals like lead, cadmium, mercury, arsenic, and cobalt at even low exposure levels, as well as organophosphate insecticides often used in agriculture and halogenated hydrocarbons and plastic-associated chemicals like bisphenol A (BPA) and phthalates ever present in our environments.

While the effects of each of these types of pollution can and do vary by geography, the global population is at risk generally, the authors say. Notably, though, they write: “Inequalities are rife in terms of exposure to pollutants and their consequences, with 92% of pollution-related deaths occurring in low- and middle-income countries.”

Miller, Kovacic, and colleagues call for several global reforms to reduce pollutants and slow the burden of climate change. They call upon individual lifestyle changes related to reducing waste and “living a more modest life” as well as country-level shifts toward renewable energy and “changes to our built environment that facilitate clean travel, close local amenities, and efficient waste removal streams.” Additionally, the authors urge governments to end the “massive subsidies” provided to the fossil fuel industry.

Within the medical field, they insist practitioners “lead by example to reduce pollution and energy inefficiency.” Specifically, they write: “The cardiovascular community, in particular, has the scale and foundations to promote the message for change, and, given the prominence of cardiovascular disease as a consequence of environmental risk factors, that voice should be justifiably strong.”

‘So Much Evidence Accumulating’

One of the biggest challenges with addressing pollution is that it’s a “collective problem,” said Stacey E. Alexeeff, PhD (Kaiser Permanente Division of Research, Pleasanton, CA), who commented on the papers for TCTMD. “It isn’t something that you can just purely control on an individual level.”

The scale of the problem is absolutely alarming. Jason C. Kovacic

Another frustration is that there are “likely many undiscovered cardiotoxins among the more than 300,000 synthetic chemicals invented in the past half century,” Alexeeff said. “There's so much that we still don't even know, basically, about what other chemicals that we have been exposed to. . . . How do we figure out what burdens some of those could be having? That’s a big research problem.”

While individual actions can contribute to change, she said the biggest impact will come from governments and other societal and cross-border commitments.

Education is at the foundation of this issue, so publication of these papers is already a start, according to Alexeeff. “The burden of pollution to cardiovascular health really is very important and we need to think about it with the same level of importance as things like diet and exercise and smoking that are factors cardiologists are already thinking about,” she said, adding that cardiologists should feel empowered to coach their high-risk patients about reducing exposure to air pollution, for example.

Kazi agreed that individuals need to be “introspective about what they can change about their carbon footprint.” But, he said, hospitals and healthcare systems should “look outward” about the effect climate change and pollution is having on patients, especially vulnerable ones.

“Health systems, in particular, can be sources of greenhouse emissions, particularly in the US,” Kazi said. “It's not just the fact that we have a lot of buildings and a lot of people. It's also that we use drugs and devices that are fairly intense in terms of their carbon footprint. And so just being cognizant of what can we do to build a greener health system is a conversation that cardiologists can contribute to.”

Cardiovascular societies should also take a more active role in advocating for climate-friendly policies within and outside of the health system, Kazi continued. “In general, cardiovascular societies have been reluctant to take this position, I guess implicitly suggesting that it feels ‘outside’ our lane,” he said. “What these and a series of other papers coming out are showing us is that this is very much in our lane, and it is affecting the health of our patients and it's doing that now. And just as we are perfectly comfortable proposing individual and societal interventions for other things that adversely affect our patient's health, we should be willing to talk about climate change as well.

“We're getting to this tipping point where there's so much evidence accumulating that at some point it will no longer be acceptable to sit on the sidelines,” Kazi added.

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Miller MR, Landrigan PJ, Arora M, et al. Environmentally not so friendly: global warming, air pollution, and wildfires: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83:2291-2307.

Miller MR, Landrigan PJ, Arora M, et al. Water, soil, noise, and light pollution: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2024;83:2308-2323.

Disclosures

- Miller reports receiving grant support from the British Heart Foundation.

- Kovacic reports receiving research support from the NIH, New South Wales health grant, the Bourne Foundation, Snow Medical, and Agilent.

- Alexeeff and Kazi report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments