Post-TAVI Pacemaker Tied to Poorer Long-term Outcomes

Whether newer pacing techniques can mitigate death, LV decline, and HF symptoms in TAVI patients remains to be seen.

VIENNA, Austria—Patients who require a pacemaker implant in the 30 days after TAVI have significantly greater risks of death up to a decade later, according to an analysis of the Swiss TAVI registry.

The risks of both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality were elevated at 1 year, with the hazards persisting over the long term, researchers observed. Patients who received a new pacemaker after TAVI were more likely to have a decline in LVEF and to have NYHA class III/IV heart failure symptoms during follow-up compared with those who didn’t require pacing.

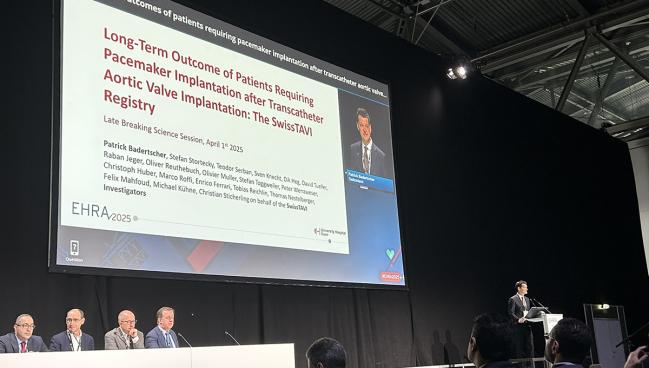

“Novel pacemaker implantation techniques, such as conduction system pacing, may result in different outcomes. However, this has yet to be demonstrated in the TAVI population,” Patrick Badertscher, MD (University Hospital Basel, Switzerland), said last week during a presentation at the European Heart Rhythm Association Congress 2025.

To TCTMD, Amit Vora, MD (Yale School of Medicine. New Haven, CT), put the findings, which were published simultaneously online in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions, into a broader context.

“As [TAVI] becomes more common in patients that are younger or lower risk, this is going to be really one of the big things that we focus on, and I think that over the last 5 years, certainly there has been a significant amount of progress that has been made with respect to reducing the risk of permanent pacemaker implantation.”

Long-term Risks

The occurrence of conduction disorders—potentially requiring a permanent pacemaker implant—remains a common complication after TAVI, Badertscher said, adding that studies looking into the prognostic impact of pacemakers have provided conflicting results.

To explore this question further, the group turned to the SwissTAVI registry, which includes centralized recording of clinical events and evaluation of outcomes. The Swiss government mandates enrollment and follow-up of all patients undergoing the procedure at the 19 TAVI centers in Switzerland.

The current analysis included 13,360 patients (mean age 82 years; 47% women) who underwent TAVI between February 2011 and June 2022 and were alive 30 days after the procedure. Mean LVEF at baseline was 56%, and 32% of patients had atrial fibrillation (AF). TAVI was performed via femoral access in 93% of cases, with 50% of patients treated with a balloon-expandable valve and 48% a self-expanding device.

Overall, 10% of patients had a pacemaker at the time of TAVI and 15% required a new pacemaker after the procedure. Those who received a new pacemaker were older on average, were more likely to be men, and had higher rates of AF, diabetes, and hypertension compared with patients without a pacemaker.

At 1 year follow-up, patients who received a new pacemaker within 30 days of TAVI had greater risks of all-cause death (adjusted HR 1.15; 95% CI 1.05-1.26) and cardiovascular death (adjusted HR 1.25; 95% CI 1.06-1.46) compared with patients without a pacemaker after multivariable adjustment. Risks didn’t differ between the patients who had a prior pacemaker and those who required a new one.

Patients who needed a pacemaker also had greater 1-year risks of having an LVEF decline of at least 10% (adjusted HR 1.88; 95% CI 1.72-2.05) and of having NYHA class III/IV symptoms (adjusted HR 1.27; 95% CI 1.05-1.54) versus those without a pacemaker. When compared with patients with a pacemaker prior to TAVI, those with a new pacemaker were more likely to have a decline in LVEF.

Moreover, patients who received a new pacemaker after TAVI—compared with those who didn’t need pacing—continued to have greater risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality at 5 years (adjusted HRs 1.16 and 1.18, respectively) and 10 years (adjusted HRs 1.16 and 1.18, respectively).

Badertscher acknowledged that the observational study was limited by the potential for residual confounding, the lack of information on ventricular pacing burden during follow-up, and the lack of an assessment of the impact of pacemaker types or indications on outcomes.

Keeping Future Options Open

Vora said these findings “generally echo” what has been seen in shorter-term studies with follow-up going out to about 3 years, with the risk of adverse events being higher in patients with pacemakers.

The number of patients who made it to 10 years of follow-up in this study was small, however, and Vora noted that “causal relationships are impossible to determine from observational studies.”

Speculating about potential ways that a pacemaker implant could worsen outcomes, Vora cited research demonstrating deleterious effects of right ventricular pacing over prolonged periods. In addition, underlying left bundle branch block or complications directly related to the pacemaker implant—like infections and lead problems—could be to blame, he added.

“These are all possibilities, but certainly not something that we can ascertain from a study like this,” Vora said.

Still, it’s important to take steps to lessen the likelihood that patients will need a pacemaker following TAVI, he indicated, noting that he and others have worked on modifying procedural techniques for both balloon-expandable and self-expanding valves in recent years to reduce risks of conduction disturbances.

A key aspect to minimizing risk of needing a pacemaker is a shallower depth of implantation for the transcatheter heart valve, but a shallower implant can also make it more difficult to perform future valve interventions, an important consideration as the procedure moves into younger patients.

“A shallower implant can sometimes make it a little bit more challenging to successfully plan and execute a valve-in-valve procedure just because of the risk of coronary obstruction, etc,” Vora explained. “And so certainly for these patients, the goal is to identify a depth of implant that will balance these competing risks and then perform the procedure in such a way that allows for precision in terms of the depth of implant.”

For patients who do require a permanent pacemaker implant after TAVI, physicians should assess both their LV function and pacing burden since there can be harmful effects of chronic RV pacing, Vora suggested. He added that alternative approaches—such as conduction system pacing—could be an option.

Indeed, said Jens Cosedis Nielsen, MD, PhD (Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark), who was the discussant for the study following Badertscher’s presentation, “These data support very much [further] studies of new pacing modalities to assess whether such will improve prognosis in patients needing pacemaker after TAVI.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Badertscher P, Stortecky S, Serban T, et al. Long-term outcomes of patients requiring pacemaker implantation after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: the SwissTAVI registry. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Badertscher reports having received research funding from the University of Basel, the Stiftung für Herzschrittmacher und Elektrophysiologie, the Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft Basel, the Swiss Heart Foundation, and Johnson & Johnson outside the submitted work; and receiving personal fees from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and BMS Pfizer.

- Nielsen reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments