Should Coronary Calcium Always Be Noted on Noncardiac CT Reports?

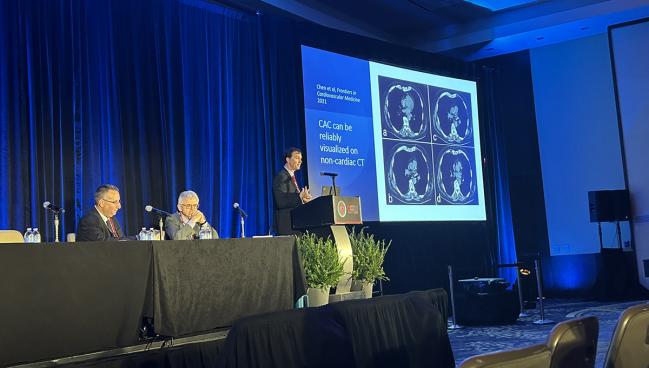

Experts at SCCT debated whether that detail should be included in all cases, considering potential unintended consequences.

WASHINGTON, DC—Whether or not the presence and degree of coronary artery calcification (CAC) should be routinely included on noncardiac CT scan reports, even when the information isn’t likely to change management, is still under discussion.

Current guidelines recommend calcium scoring for a specific subset of patients for whom the decision about whether to initiate lipid-lowering therapy is uncertain, but whether information obtained incidentally should be routinely reported was the topic debated here at the 2024 Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT) meeting.

Michael Blaha, MD (Johns Hopkins Ciccarone Center for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease, Baltimore, MD), told attendees that this information—which doesn’t cost anything—always should be included.

“It’s really, in my opinion, up to the treating clinicians to decide what to do about incidental calcification, not necessarily the reader to say, ‘Well, I think in this case I should report it, this case I shouldn’t,’” he said. “I think we should let the clinician know and let the clinician at the bedside decide.”

Marcio Sommer Bittencourt, MD, PhD (University of Pittsburgh, PA), countered by pointing out that for many patients who are already deemed to have a high risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) based on other factors, the inclusion of information on incidental CAC would be superfluous.

“Although we can measure it, it may not be needed for everybody,” he said.

Routine Reporting Already in the Guidelines

Blaha argued, in his side of the debate, that CAC information should always be reported for noncardiac chest CTs, starting out by reviewing studies showing that CAC can be reliably visualized on noncardiac CT and accurately assessed by different readers, even nonexperts, to place patients in clinically meaningful categories based on the degree of calcification.

That classification can be done with the modified Agatston score, an ordinal score, or a simple visual score (ie, none, mild, moderate, or severe CAC). Blaha said, however, that a tool combining ordinal scoring and the visual assessment proposed in a 2018 consensus document from the SCCT—the Coronary Artery Calcium Data and Reporting System (CAC-DRS)—should be used.

Importantly, incidental CAC on noncardiac chest CTs has been shown to be associated with risk of cardiovascular outcomes, Blaha said, citing a recent review in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Of course, we’re not going to move the needle unless the incidental calcification actually changes patient and physician behavior,” he said.

On that point, Blaha continued, the results of the NOTIFY-1 Project show that it can. In the trial, patients without known ASCVD or a prior statin prescription were screened for CAC on already performed noncardiac chest CTs with a deep-learning algorithm. Those with incidental CAC were then randomized to be notified along with their primary care physician or to continue with usual care. At 6 months of follow-up, the rate of statin prescription was 51.2% in the notification arm and just 6.9% in the control arm, “which I think we can all agree is going to improve patient outcomes,” Blaha said.

He also argued that making the reporting of incidental CAC routine will improve consistency and make things easier than using more selective reporting. Routine reporting becomes a habit, can be built into report templates, and is unaffected by a patient’s risk profile. Selective reporting, on the other hand, will result in more variability because the readers will have to decide based on patient factors whether CAC should be included on the report and might also forget about it altogether.

Perhaps the strongest argument for always including CAC information, however, is that such an approach is already recommended by the SCCT and the Society of Thoracic Radiology, Blaha said.

“It’s free information. It’s readily and reliably interpretable. There’s a simple communication framework for it. It’s highly prognostic. It changes management. It’s already class I in the guidelines,” he concluded.

Incidental CAC Not Helpful in All Cases

Bittencourt focused his counterargument on highlighting the questionable relevance of incidental CAC for many patients—beyond those singled out in the guidelines.

He presented a few cases as examples of situations in which additional information about CAC would be unlikely to modify risk assessments and, therefore, treatment decisions. One was a 64-year-old man with hypertension and hyperlipidemia who had an MI 5 years before undergoing a nongated chest CT for the evaluation of a pulmonary nodule seen on chest X-ray. The scan showed severe coronary calcification but because the patient was already at high risk for ASCVD events, “is this going to change your management?” Bittencourt asked.

Another case was a 70-year-old man who was a heavy smoker and had a calculated ASCVD risk of 20.2%, but who also had normal blood pressure and well-controlled LDL cholesterol on atorvastatin. A chest CT for lung cancer screening showed no significant coronary calcification. Bittencourt questioned whether that information would change anything considering the high calculated risk of CV events even in the absence of calcium.

To broaden his point, he pulled data from a recent study of patients undergoing lung cancer screening. Most participants (62%) had either a high calculated ASCVD risk, diabetes, or a prior MI and would be receiving statins to prevent CV events regardless of the presence of CAC, he said. And, he pointed out, of the 2,880 patients in whom coronary calcium was reported from their chest CTs, only 3% were newly started on statins.

“So you can do it,” Bittencourt said about routinely reporting incident CAC. “Is that helpful? Does it change management? By very little. And you can say, ‘Well, still it’s for free.’ But well, is it helping much? I’m not so sure.”

Another factor to consider is that while it may not cost anything to include incidental CAC on a report, that doesn’t mean there aren’t potential downstream effects. In the study of lung cancer screening, he noted, 9% of those with significant CAC and 6% of those with nonsignificant CAC went on to get a stress test. “So it’s not free,” Bittencourt said. “It has a cost, and the cost may have [a] negative impact.”

“Maybe we don’t need to do it for everybody,” Bittencourt said. “We need to do it for the ones that have an intermediate risk and may benefit from the decision.”

Communication Is Key

In his rebuttal, Blaha addressed concerns that knowing about incidental CAC may cause patients anxiety by underscoring the importance of solid communication from physicians.

“It’s about shared decision-making and education,” he said. “We need appropriate communication about what the calcium score means and shared decision-making with the patient. It may be difficult, but it can be done.”

Blaha added that it’s possible artificial intelligence someday will be able to help decide when it’s appropriate to report incidental CAC on a noncardiac chest CT report.

Bittencourt, given the last word, also touched on the importance of communication when reporting incidental CAC. “I’m not here to say you should not do it. I’m just saying that you have to create the right expectations of the impact of what you’re doing and that depends a lot more on how we coach the clinicians to understand what we do.”

He added that a space for CAC should be included on report templates, saying that “we can delete the line of the template when it’s not needed.”

Overall, Bittencourt said, “it is free, but it may have some cost if you don’t do it right.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Multiple presentations. Presented at: SCCT 2024. July 19, 2024. Washington, DC.

Disclosures

- Blaha reports grants and research support from GE Healthcare and Varian-Siemens.

- Bittencourt reports speaking for Cleerly and serving on the scientific board for Elucid.

Comments