Slight Advantage for DES Over DCB for In-Stent Restenosis: Updated Meta-analysis

Though angiographic outcomes are slightly worse with drug-coated balloons, experts agree that they’ll continue to have a clinical role.

Angiographic outcomes are slightly worse with drug-coated balloons (DCB) than with second-generation DES for treating in-stent restenosis, an updated meta-analysis confirms. But experts say there are times when the benefits of DCB outweigh that disadvantage.

Pooling results from seven trials, investigators led by Islam Elgendy, MD (University of Florida, Gainesville), found that DCB use was associated with lower in-segment minimum lumen diameter and higher in-segment diameter stenosis—but lower late lumen loss—at a mean follow-up of 8.2 months when compared with DES use.

Moreover, DCB use carried a greater risk of TLR at a mean follow-up of 27 months (11.4% vs 5.6%; risk ratio 1.83; 95% CI 1.07-3.13). Rates of a variety of other clinical outcomes, including TVR, MI, stent thrombosis, all-cause mortality, and MACE, did not differ between groups.

The findings of the meta-analysis, published online January 10, 2019, ahead of print in the American Journal of Cardiology, are essentially the same as the results of a prior meta-analysis by Elgendy’s group that included two fewer trials.

Speaking with TCTMD, Elgendy—who pointed out that DCB are not currently approved in the United States for use in the coronary vasculature—said second-generation DES should be the preferred option for in-stent restenosis. He indicated that DCB can be useful in certain situations, however.

“I still believe DCBs have a role because essentially we’re saving another stent layer, but it’s about finding the correct or best lesion that should be treated with DCBs,” Elgendy said. The devices might be best suited for treatment of lesions in smaller vessels and for patients who have already had in-stent restenosis treated with another stent, he said.

I still believe DCBs have a role because essentially we’re saving another stent layer, but it’s about finding the correct or best lesion that should be treated with DCBs. Islam Elgendy

Commenting for TCTMD, Robert Byrne, MBBCh, PhD (Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Germany), who is involved in a separate effort to evaluate individual patient-level data from the DCB trials called DAEDALUS, said DCB have an important place in the cardiac cath lab. He noted that the European myocardial revascularization guidelines have equivalent class I (level of evidence A) recommendations for DES and DCB for treatment of any in-stent restenosis.

Thus, he said, European operators are comfortable with either approach and the decision about which to use is individualized. Though angiographic results are better with repeat stenting, there has been some concern—based on results from ISAR-DESIRE 3 and other studies using first-generation DES—about long-term safety in terms of risks of death or MI out to 2 or 3 years when a second stent is placed. “Many of us feel that the slightly inferior angiographic performance [with DCB] is acceptable because of the potentially increased risk of late adverse events with stent-in-stent,” Byrne said. “It’s still a case-by-case decision.”

Incorporating New Trial Data

The prior meta-analysis by Elgendy et al included five trials that compared second-generation DES with DCB for in-stent restenosis: RIBS IV, RIBS V, TIS, SEDUCE, and DARE. For the updated meta-analysis, the investigators added two more published in the last year (RESTORE and BIOLUX), bringing the total number of patients to 1,363. A paclitaxel-coated balloon was used in all DCB-treated patients and an everolimus-eluting stent was used for DES-treated patients in all but one trial, in which a second-generation sirolimus-eluting stent was used. Mean reference vessel diameter ranged from 2.5 to 3.0 mm across trials.

The addition of the new trials did not have a meaningful effect on the results of the meta-analysis. DCB use was still associated with a higher risk of TLR, a finding consistent in the subgroup of patients with restenosis of a DES (RR 1.88; 95% CI 1.08-3.20).

None of the trials were powered to detect differences in clinical outcomes, but, Elgendy et al say, “it is reassuring that there were no differences between both strategies on the incidence of MACE, TVR, MI, stent thrombosis, and all-cause mortality.

“Thus, future studies should focus on identifying lesions that might obtain excellent angiographic and clinical outcomes with DCB,” they write. “Although this analysis might be limited by the methodological heterogeneity due to the different types of paclitaxel-eluting balloons, we noted minimal statistical heterogeneity for TLR.”

Choosing the Right Approach

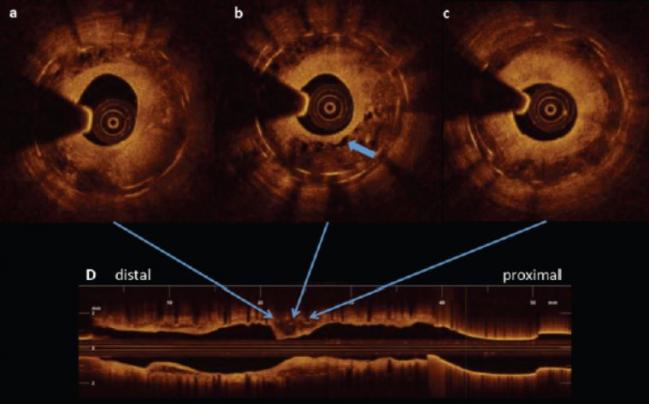

Byrne said the first thing that needs to be done to decide between a DES and DCB for in-stent restenosis is to determine whether there is a geographic miss or mechanical defect such as fracture or longitudinal deformation with the implanted stent. If one of those issues exists, it’s probably best to put another stent in, he said.

If not, a choice needs to be made, Byrne said, noting that in his practice, the default approach is DCB for a first-time restenosis with intact mechanical integrity of the underlying stent followed by repeat stenting if the patient presents with another restenosis after that.

Commenting for TCTMD, Jonathan Marmur, MD (SUNY Downstate Medical Center, New York, NY), highlighted patients with recurrent in-stent restenosis as good potential candidates for DCB treatment.

“The problem you run into is you put multiple stents in and you can get to the point where you have three or four layers of stent and they keep coming back,” Marmur said. “And those are the ideal patients where I think this balloon technology is most appropriate.”

It’s not surprising that DES provide better angiographic outcomes compared with DCB, he added, because balloons can lead to dissections and come with some degree of elastic recoil. “For all the reasons that stents work better than balloon angioplasty in de novo lesions, they also give a better result in in-stent restenosis,” Marmur explained. But because multiple layers of stent can act as a nidus for stent thrombosis and restenosis, he said, “it’s conceptually attractive to avoid permanent implantation of foreign material [by using] the drug-eluting balloon.”

Robert Schwartz, MD (Minneapolis Heart Institute and Foundation, MN), described DCB as a “niche treatment,” but one that could be useful in certain scenarios—for lesions in small vessels, lesions at the ends of stents, and patients in whom “you’re really loathe to use clopidogrel or any of the other potent antiplatelet agents,” for example.

Coming to America?

American interventionalists will have to wait for the opportunity to deploy DCB in the coronary vasculature, since the US Food and Drug Administration has yet to clear that use. Schwartz suggested that there will be a receptive audience if and when that happens: “There’s a lot of people hungry to see them. . . . It’s a niche tool but it would be a nice tool to have in the interventional toolkit.”

Marmur agreed, saying that “there’s definitely a clinical role for this,” perhaps in up to 20% of patients with in-stent restenosis. “For the majority of cases, I would anticipate that the stents are so effective that the majority of lesions would still be treated with stenting, but there is a subpopulation where additional stenting would be seen as unfavorable.”

From his European perspective, Byrne said there might be a couple of explanations for the FDA’s reluctance to approve coronary use of DCB. In general, he said, the regulatory bar is higher in the US than in Europe, with a requirement for larger-scale clinical trials. DCB trials have been powered not for clinical outcomes, but for surrogate endpoints.

Safety could also be a concern, Byrne suggested, as there is some evidence from animal models that DCB use is associated with microparticulate formation in the downstream vasculature. “This is something the regulatory authorities in the US, I understand, are quite hot on,” he said. “We would feel that while this may be seen in the animal models, in clinical practice it doesn’t cause a problem and we don’t see, for example, higher rates of myocardial infarction after drug-coated balloon angioplasty than we do after repeat stenting.” He added that his group also did an analysis of “microtroponin leaks” and did not find a difference between DCB and repeat stenting.

Last month, as reported by TCTMD, a meta-analysis linking paclitaxel-coated balloons (and paclitaxel-eluting stents) to adverse events in the setting of peripheral artery disease prompted the halt of two DCB trials. A range of upcoming meetings have convened special sessions to address the issue and the FDA has reportedly requested data from DCB manufacturers.

In the meantime, Byrne said, DCBs fill “a genuine unmet need” in the coronary space.

“Restenosis is something we still see in our daily practice and I think patients aren’t invariably best served with repeat stenting with DES,” he said. “I think the interventionalist is well served if they have another option such as DCB angioplasty on their cath lab shelf.”

Photo Credit: Robert Byrne

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Elgendy IY, Mahmoud AN, Elgendy AY, et al. Meta-analysis comparing the frequency of target-vessel revascularization of drug-coated balloons or second-generation drug-eluting stents for coronary in-stent restenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2019;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Elgendy and Schwartz report no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Byrne reports receiving lecture fees/honoraria from B. Braun Melsungen AG, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, and Micell Technologies, as well as research grants to his institution from Boston Scientific and CeloNova BioSciences.

Comments