Statins Provide No Clinical Benefit When Coronary Calcium Is Zero, Study Shows

The study was published just ahead of the upcoming cholesterol guidelines, with experts wondering if CAC testing will finally be given a seat at the table.

Statin therapy for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease fails to have an impact on clinical outcomes in patients without evidence of coronary plaque, a new study shows. These results suggest that an assessment of coronary calcification could be used to identify patients most likely to benefit from the lipid-lowering therapy, particularly those in whom physicians might be on the fence about treating, say investigators.

“Coronary artery calcium screening has been proposed as a means to better improve risk prediction in patients, but no studies have looked directly at the impact of treatment,” lead investigator Joshua Mitchell, MD (Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO), told TCTMD. “We don’t have information, or we don’t truly know how the screening test best fits in with management decisions. At what point in time do you decide to use a statin in a patient versus not using one?”

In the new study, which was published online October 31, 2018, ahead of print in the Journal of American College of Cardiology, researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of 13,644 patients who underwent coronary artery calcium (CAC) screening between 2002 and 2009 at Walter Reed Army Medical Center to determine the effects of statins on cardiovascular events. Overall, patients had a low burden of risk factors for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and more than two-thirds had no detectable CAC. Of those included in the analysis, 6,886 were treated with a statin, with nearly half of these patients prescribed the lipid-lowering therapy in the 6 months before the CAC test. Two-thirds of patients were treated with a moderate-intensity statin and 19.3% received a high-intensity statin. The median follow-up was 9.4 years.

In an analysis comparing patients positive or negative for coronary calcium (any amount greater than zero), patients with detectable CAC prescribed a statin had a 24% lower relative risk of MI, stroke, or cardiovascular death when compared with those with evidence of CAC not treated with a statin (adjusted subhazard ratio 0.76; 95% CI 0.60-0.95). In contrast, among patients with no evidence of calcification (CAC score = 0), there was no difference in the risk of major cardiovascular events among those treated with a statin compared with those not treated with a statin.

For the overall cohort, the effect of statin therapy on the risk of major cardiovascular events appeared related to the severity of CAC (P < 0.0001 for interaction). For example, there was a 17% reduction in relative risk with statins among those with a CAC score of 1 to 100 but a 68% reduction in relative risk among statin-treated patients with a CAC score of 101 to 400. There was a 44% reduction in cardiovascular events among statin-treated patients with a CAC score above 400.

In a sensitivity analysis where investigators analyzed patients compliant with statin therapy, the results were similar to the overall findings, with the benefit of statin therapy related to CAC severity. For patients with a CAC score of 1 to 100, the number needed to treat to prevent one major cardiovascular event was 100. For those with a CAC score above 100, just 12 patients would need to be treated to prevent an event.

Shaking Up Risk Assessments

The current guidelines recommend starting moderate- to high-intensity statin therapy in patients ages 40 to 75 years without cardiovascular disease who have a 10-year ASCVD risk ≥ 7.5%. The 10-year risk of ASCVD is currently estimated using the patient’s age and traditional cardiovascular risk factors, but proponents of CAC screening believe an assessment of plaque burden improves the accuracy of the score.

“Most of the work over the past 5 years has clearly showed how calcium—not only the presence but also the absence of disease—is critical to unlocking value,” said Khurram Nasir, MD (Yale University, New Haven, CT), referring to the value of statin therapy. The benefit of CAC to aid in treatment decisions is most pronounced in intermediate-risk patients, those with a 10-year risk ranging from 5% to 20%. “There are patients you can avoid treating,” he added.

The use of CAC as a decision aid changes the treatment paradigm, shifting it from a scattershot method targeting all intermediate-risk patients to a more precise approach where physicians can identify who needs a statin and who doesn’t. “You can reassure millions of those individuals in that 5% to 20% risk range with a calcium score of zero that it is OK to forgo a statin and follow an aggressive lifestyle management path instead,” Nasir told TCTMD.

Although the gold standard remains a randomized clinical trial to assess CAC-guided preventive therapy in patients with risk factors for ASCVD, Mitchell said such a trial is unlikely to be performed given the lack of clinical equipoise. Specifically, no study would be approved where patients with coronary calcification and risk factors for ASCVD are randomized to statin therapy or placebo, he said.

Prior Studies, New Guidelines

Several other studies published to date, however, including data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study, and the BioImage study, showed that CAC could help identify individuals who would most benefit from statin therapy. The Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT) supports the use of CAC to help guide treatment decisions, but the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently published a statement that said they found the evidence “inadequate” when it comes to use of CAC screening to aid in treatment decisions.

For Nasir, who wrote an editorial accompanying the study, the results—which “clearly demonstrate” that statin benefit is tied to presence of ASCVD as documented by CAC—are not surprising. “As we have been advocating for almost a decade, if you had a calcium score of zero, especially if you’re not at high risk, your baseline risk is at such a low threshold that committing to a statin for an indefinite period is unlikely to benefit,” said Nasir.

Mitchell agrees that CAC screening is a useful tool for deciding on statin therapy in patients at intermediate risk for ASCVD. In a post hoc, exploratory analysis, the researchers found that statin therapy reduced the risk of major cardiovascular events in high-risk patients even if they had no evidence of CAC, while there was no benefit of statin therapy in patients without CAC at low or intermediate risk of ASCVD.

“The general recommendation is that in [high-risk] patients, they would just be treated with a statin,” said Mitchell. “The benefit of a CAC score in those patients might be to reinforce that they need to be on a statin if they’re reluctant to take one, but we wouldn’t do a CAC score in everyone.” CAC imaging could be used to enhance shared decision-making between patient and physician or if there is a question as to whether they would benefit from a statin or not, he added.

New guidelines for the management of cholesterol will be released November 10 at the American Heart Association (AHA) 2018 Scientific Sessions: many are wondering whether the new recommendations will include the use of CAC screening to guide treatment.

Discussing the intent of the new guidelines—but not their content—with the press last week, AHA program committee co-chair and guideline co-author Donald Lloyd-Jones, MD (Northwestern University, Chicago, IL), hinted that changes are afoot. “There’ve been questions about when should we use risk scores, are there some risk scores that are better than others, or are there strategies of risk assessment that we should be deploying beyond risk scores?” he said. “This is an area of much discussion in the guidelines, and I think you’ll see some pretty significant advances in terms of how we think about patients and who might be appropriate for using statin therapy and who might be appropriate for withholding statin therapy because it’s unlikely they will benefit.”

Mitchell said he believes it’s time for the guidelines incorporate coronary calcium.

“Coronary artery calcium definitely deserves a place in the guidelines for use,” he said. “I think there has been a significant amount of evidence that shows a coronary calcium score improves risk prediction of who is going to have events better than any other biomarker or test . . . . It can tell you who might have lower risk than you previously thought or who might be at higher risk than you thought. When compared with any other test that we have, it has a better ability to accurately predict those events.”

To TCTMD, Nasir said he is hopeful the new guidelines factor in the “power of zero” with respect to CAC. “We have convincing data that calcium testing should be afforded at least a class IIa recommendation, but what I want to emphasize is that this isn’t a screening test. It’s not screening—you’re using this test in the intermediate group who are already candidates for a statin. You’re using it as a decision aid to define not only who will benefit but who will not benefit.”

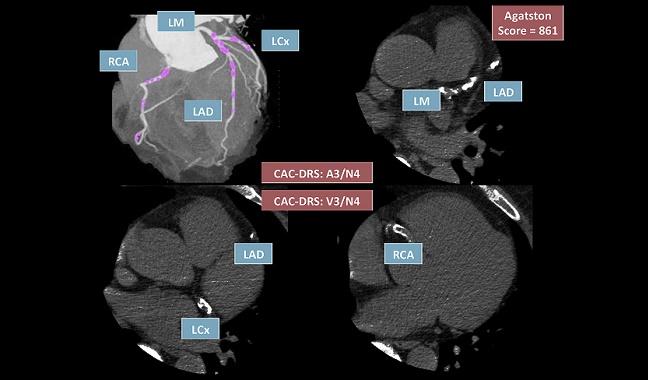

Photo Credit: Reprinted from Journal of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Volume 12 / Edition 3, Hecht HS, Blaha MJ, Kazeroonic, EA et al. CAC-DRS: Coronary Artery Calcium Data and Reporting System. An expert consensus document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT). Pages 185-191. Copyright (2018), with permission from Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Mitchell JD, Fergestrom N, Gage BF, et al. Impact of statins on cardiovascular outcomes following coronary artery calcium screening. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;Epub ahead of print.

Nasir K. Message for 2018 cholesterol management guidelines update: time to accept the power of zero. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Mitchell and Nasir report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments