Surgical Management of Acute PE Provides Good Outcomes

When putting together PERTs, surgeons deserve a seat at the table, experts say.

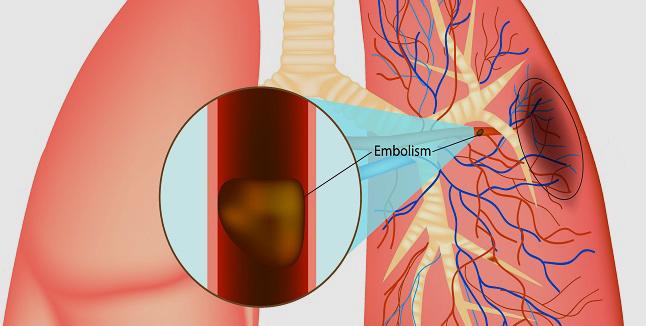

Often relegated to the second or third tier of treatment options, surgical management of patients with massive or high-risk submassive acute pulmonary embolism (PE)—either with embolectomy or venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO)—safely boosts RV function, a single-center study suggests.

Use of either technique was associated with improvements in central venous pressure, pulmonary artery systolic pressure, RV/LV ratio, and fractional area change, according to researchers led by Joshua Goldberg, MD (Westchester Medical Center, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY).

The in-hospital mortality rate was 4.4% overall, and lower still in patients who did not undergo preoperative CPR (1.7%). No deaths were secondary to RV failure, the investigators report in a study published online ahead of the August 25, 2020, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“What we demonstrate here is that the patients do really well,” Goldberg told TCTMD. “The mortality is low, the morbidity is low, and their right ventricles recover.”

Even though the first pulmonary embolectomy was done about a century ago, there’s relatively little written about surgical management in the PE literature, he noted. “Because the original procedure had such high mortality, well over 50%, it created sort of a dark cloud, a shadow, over surgical embolectomy so that in the minds of surgeons and the minds of other providers it was seen as a Hail Mary type of situation.”

For that reason, much of the literature around surgical management includes studies of “salvage” patients who failed or were not eligible for medical or transcatheter treatment. “So to compare surgical embolectomy to other procedures is not a fair comparison,” Goldberg said. “It’s comparing apples and oranges, because you’re dealing with a much sicker population.”

But surgical embolectomy has evolved over the years, and surgeons now use cardiopulmonary bypass, cool the heart, and take out clot extending into the peripheral pulmonary vasculature. The current study shows that those advancements have paid dividends and may influence how both clinicians and guideline writers view surgical management of acute PE, Goldberg said.

“I think this paper and some smaller papers really are developing a convincing argument that surgery should be considered as an early treatment option,” he argued, acknowledging that the findings can’t inform relative safety and effectiveness versus medical or transcatheter options. “But I think what it does demonstrate, along with some smaller similar series, is that surgery is a safe and very effective option.”

This is all the more important as hospitals have begun putting together multidisciplinary pulmonary embolism response teams (PERTs) to enhance care.

Reconsidering Surgery

In various guidelines, surgical management either isn’t mentioned or is recommended as a second- or third-tier option for patients with acute PE, both because of the limited evidence and the fact that studies have largely been confined to sicker populations, Goldberg noted.

I think this paper and some smaller papers really are developing a convincing argument that surgery should be considered as an early treatment option. Joshua Goldberg

To provide a more contemporary look at surgical techniques, the investigators analyzed data on 136 patients (mean age 57.7 years; 58.1% men) who were treated at their center between 2005 and 2019. About one-third had a massive PE (objective evidence of RV dysfunction and hemodynamic instability) and the rest had a high-risk, submassive PE (objective evidence of RV dysfunction and hemodynamic stability). Preoperative CPR was used in 43.2% of patients with a massive PE and in none of those with submassive PE.

All but one of the patients with submassive PE were treated initially with surgical embolectomy, with just one receiving venoarterial ECMO. In the massive PE group, 59.1% initially underwent surgical embolectomy and 40.9% were treated with venoarterial ECMO.

Regardless of the severity of the PE, patients presented with severe RV dysfunction. In both groups, RV function normalized by discharge. Specifically, there were improvements in central venous pressure (from 23.4 to 10.5 mm Hg), pulmonary artery systolic pressure (60.6 to 33.8 mm Hg), RV/LV ratio (1.19 to 0.87), and fractional area change (26.8 to 41.0; P < 0.05 for all).

In-hospital mortality was low overall, although it was much higher in patients who did versus did not undergo CPR (25.0% vs 1.7%). Strokes occurred in 2.2% of patients, and there was a need for mechanical ventilation lasting more than 72 hours in 18.4%; rates were higher in patients with massive versus submassive PE. Reoperation for bleeding was needed in 2.2%.

“To put our outcomes in perspective, our observed mortality rate of 1.7% among patients who did not require CPR is comparable with the mortality rates observed among 156,931 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting surgery (1.7%) and 28,037 patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement (1.6%), as reported in the 2016 Society of Thoracic Surgeons Adult Cardiac Surgery Database,” Goldberg et al write in their paper.

Don’t Forget the Surgeons on PERTs

Commenting for TCTMD, Gregory Piazza, MD (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), said, “We’ve had surgical-based management for PE, especially with embolectomy, for decades but we don’t spend a lot of time talking about it so immediately this fills an important gap in providing us with contemporary numbers on how our patients do when they get embolectomy or ECMO.”

And the outcomes observed in this series were “very good,” Piazza said. “Typically people avoid surgical management of PE because in the older literature it suggested that if you managed patients surgically they didn’t do particularly well. A lot of that has to do with the fact that if your patient’s sick enough to need surgery they’re going to have a poorer outcome anyways. These data show that patients with our contemporary techniques can do really well.”

When it comes to PERTS, surgeons need to be part of that process, Piazza said. “They have to be involved because surgical management of PE is becoming, especially based on this study, an important option for us to have—especially for circulatory support with ECMO, but also with embolectomy. So really when you’re constructing a comprehensive PE management team, you need to include surgeons.”

Goldberg agreed, saying, “The medical community has really come together over the last several years to develop a multidisciplinary approach to evaluating and treating these patients, and I think it’s very important that given these data and others that surgery is closely involved in the decision-making process. Because I think that this is a treatment that can really save a lot of lives in the most-ill patients if they’re treated expeditiously.”

How surgical management can fit in with the other options, including anticoagulation, thrombolysis, and catheter-based therapies, is unclear, Samuel Goldhaber, MD (Brigham and Women’s Hospital), highlights in an accompanying editorial along with numerous other open questions.

“Like most good studies, their paper is thought-provoking and provides us with pathways for further research and clinical exploration,” he writes.

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Goldberg JB, Spevack DM, Ahsan S, et al. Survival and right ventricular function after surgical management of acute pulmonary embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:903-911.

Goldhaber SZ. ECMO and surgical embolectomy: two potent tools to manage high-risk pulmonary embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:912-915.

Disclosures

- Goldberg, Goldhaber, and Piazza report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments