Value of Ambulatory BP Monitoring Bolstered by Large Study

Ambulatory measurements were more tightly linked with mortality than clinic readings in a Spanish primary care registry.

Readings obtained with ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) are more strongly associated with risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than are measurements taken in the clinic, a large Spanish registry study affirms. The findings provide fodder for ongoing debates about the best way to measure BP and may have implications for how guideline-directed treatment of hypertension should be implemented.

As seen in prior smaller studies, the superiority of ABPM values for predicting risk was consistent “across a wide range of clinical scenarios (by age, sex, and the presence or absence of obesity, diabetes, prior cardiovascular disease, and antihypertensive drug treatment),” lead author José Banegas, MD (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Spain), told TCTMD in an email. “The differences are striking.”

The analysis, published in the April 19, 2018, issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, also revealed that two conditions dependent on ABPM for detection—white coat hypertension (high clinic BP and normal ABPM values) and masked hypertension (normal clinic BP and high ABPM values)—carry mortality risks that meet or exceed those seen in patients with sustained hypertension (high BP both in the office and on ABPM).

“Our study is the largest worldwide and provides unequivocal evidence that ABPM is superior to clinic pressure at predicting total and cardiovascular mortality,” Banegas said.

“A hypertension diagnosis based exclusively on blood pressure readings in the clinic is no longer acceptable,” he argued. “There is no scientific or clinic justification for not using ABPM, which should be part of the evaluation and follow-up of most hypertensive patients. Where ABPM is not available or affordable, home blood pressure monitoring would be an alternative.”

Highest Risk With Masked Hypertension

Banegas et al examined data from the ongoing Spanish Ambulatory Blood Pressure Registry, which recruits patients who have a guideline-recommended indication for ABPM from 223 primary care centers across Spain. The current analysis included 63,910 adults enrolled between March 2004 and December 2014.

A hypertension diagnosis based exclusively on blood pressure readings in the clinic is no longer acceptable. José Banegas

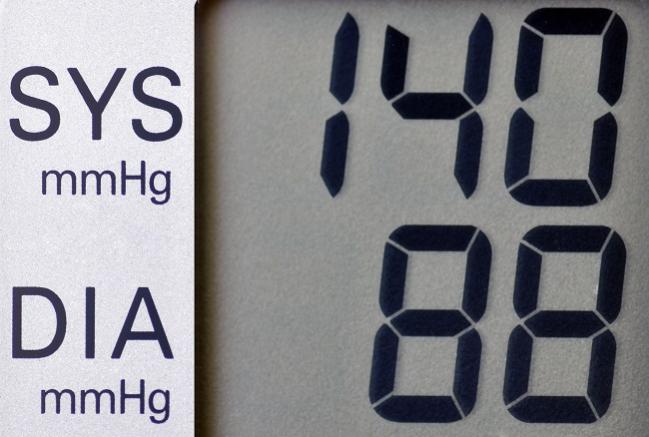

Overall, 6.6% of patients were normotensive both in the clinic and on ABPM, 10.5% had controlled hypertension, 27.7% had white coat hypertension, 8.4% had masked hypertension, and 46.8% had sustained hypertension. The last three categories included patients who were either untreated or uncontrolled on medications. Overall, mean clinic BP was 148/87 mm Hg and mean ambulatory pressure was 129/77 mm Hg.

Through a median follow-up of 4.7 years, 3,808 patients died from any cause, including 1,295 from cardiovascular disease.

Both clinic and ABPM values were associated with risks of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality, but the relationships were much stronger for ABPM.

For example, a 1-standard deviation (SD) increase in 24-hour systolic pressure was associated with a 58% relative increase in the risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.58; 95% CI 1.56-1.60) after adjustment for clinic pressure. The association was weaker for clinic systolic pressure (HR 1.02; 95% CI 1.00-1.04) after adjustment for the ABPM value.

The strength of the relationship with ABPM was similar when looking just at nighttime or daytime systolic readings. Moreover, adding ABPM measures to a model that included cardiovascular risk factors resulted in better discrimination of mortality risk than did adding clinic BP values.

Looking at specific phenotypes, untreated white coat hypertension carried a risk of all-cause mortality (HR 1.79; 95% CI 1.38-2.32) that was similar to the risk seen with untreated sustained hypertension (HR 1.80; 95% CI 1.41-2.31); this finding contrasts with prior studies showing that risk was not elevated or only partially heightened in patients with white coat hypertension compared with normotensives. That “may partly be due to the higher mean blood pressure over 24 hours in these patients (vs normotensives) or their worse metabolic phenotype,” Banegas said.

The highest risk of all-cause mortality, however, was observed in patients with masked hypertension who were not taking antihypertensive medications (HR 2.83; 95% CI 2.12-3.79).

Patients who had masked hypertension despite taking medication had a greater risk of all-cause mortality (HR 2.61; 95% CI 2.14-3.17) compared with those with controlled hypertension.

The findings were similar when looking at cardiovascular mortality as the endpoint.

The excessive risk seen in patients with masked hypertension “might be due to the delayed detection of masked hypertension in patients, who consequently could have more organ damage and cardiovascular disease than patients with sustained hypertension,” Banegas et al speculate.

Call for an ABPM Registry in the United States

In an accompanying editorial, Raymond Townsend, MD (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia), says, “The take-home message from this study is that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is a valuable tool in the assessment of the most important and treatable factor worldwide contributing to premature death and disability, namely, blood pressure.”

In addition, he says, the study provides an example of the value of ABPM registries.

Townsend told TCTMD that he began to organize a US registry about 2 years ago when he was vice president of the American Society of Hypertension, but that the effort hit a snag when the society dissolved and its membership was absorbed into the American Heart Association.

The main obstacle standing in the way of an ABPM registry in the United States, however, is the difficulty physicians have in getting reimbursed for performing the monitoring, Townsend said. Reimbursement is available through a CPT code for high blood pressure in the absence of hypertension, but that typically only brings back roughly $48 to $100. That doesn’t really cover the costs of ABPM, which involve the monitors themselves, batteries, paper, computer software, maintenance, having a nurse or medical assistant apply and then remove the device, and having a clinician interpret the findings, Townsend said.

Even though ABPM is performed at centers around the country despite the reimbursement difficulties, there is still no money available to set up and maintain a registry, he said.

“If you want to do a good job . . . you have to have government buy-in and healthcare providers and policy makers willing to support these kinds of programs,” Townsend said.

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Banegas JR, Ruilope LM, de la Sierra A, et al. Relationship between clinic and ambulatory blood pressure measurements and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1509-1520.

Townsend RR. The value in an ambulatory blood-pressure registry. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1555-1556.

Disclosures

- The study was supported by the Spanish Society of Hypertension and by an unrestricted grant from Lacer Laboratories, Spain. Specific funding for this analysis was obtained from a grant from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias of Instituto de Salud Carlos III (cofunded by Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional and Fondo Social Europeo) and from Centro de Investigacion Biomedica en Red of Epidemiology and Public Health, Spain.

- Banegas reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Townsend reports receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health and personal fees from Medtronic, AXIO, Clarus Therapeutics, Continuing Medical Education, and UpToDate.

Comments