Absorb BVS Again Linked to Scaffold Thrombosis at 1 Year and Beyond

An updated meta-analysis confirms the perils of using Absorb BVS, with investigators reporting scaffold thrombosis risks well beyond 1 year.

Use of the Absorb bioresorbable vascular scaffold (BVS, Abbott Vascular) is associated with an increased risk of definite or probable scaffold thrombosis at 1 year and beyond, as well as increased risks of MI and target lesion failure, according to the results of yet another study casting the now unavailable device in a critical and unfavorable light.

In a meta-analysis of several high-profile studies with extended follow-up to a median of 25 months, the risk of definite/probable scaffold thrombosis was nearly three-and-a-half times greater among patients who received the Absorb device compared with patients treated with everolimus-eluting metallic stents (OR 3.40; 95% CI 2.01-5.76).

The results, which were published this week in the Annals of Internal Medicine, are unlikely to shock physicians familiar with the bioresorbable scaffold, nor are they likely to have much clinical impact given Abbott’s recent decision to stop selling Absorb BVS due to low commercial sales.

Led by Xin-Lin Zhang, MD (Nanjing University School of Medicine, China), the meta-analysis is an update on a 2016 study conducted by the same research group. While the results are unsurprising, Jeptha Curtis, MD (Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT), who wrote an editorial along with Sanket Dhruva, MD (Yale University School of Medicine), told TCTMD they provide longer-term information about the clinically meaningful differences between BVS and drug-eluting stents.

“It’s another signal confirming that there are reasonable concerns about bioresorbable vascular scaffolds,” said Curtis. “We’re seeing [adverse events] in multiple databases fairly consistently. This is coming in at the end after it’s already being pulled off the market, so the clinical implications are somewhat limited at this point. Nevertheless, it really highlights the need for surveillance of new devices.”

In the editorial, Curtis and Dhruva say the updated meta-analysis would have been easy to discount as a marginal incremental advance, but that its publication is a credit to the authors and the journal’s editorial staff. For the editorialists, the findings show that the hypothesized benefits of BVS—complete resorption allowing the artery to positively remodel—have not panned out. “[I]t seems increasingly unlikely that any BVS platform will put a dent in the dominance of metallic stents,” they write.

Gregg Stone, MD (Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY), who led the global ABSORB research program, said these new data are consistent with previously published meta-analyses showing either trends or increased risk of adverse events with Absorb compared with the cobalt-chromium everolimus-eluting stents within the first year and beyond.

With thicker struts and limited expansion capability, the first-generation device needs to be improved to reduce the risk of adverse events, said Stone. However, he also noted that most of implantations part of the ABSORB studies were performed in the “early learning” phase.

“We’ve since learned that the techniques that we used to implant the device were suboptimal,” he told TCTMD.

Risk of Scaffold Thrombosis Doubles Beyond 1 Year

The updated meta-analysis included seven randomized trials and 38 observational studies in adults with coronary artery disease treated with Absorb or an everolimus-eluting metallic stent. The randomized trials included ABSORB II and III, ABSORB China, ABSORB Japan, AIDA, TROFI II, and EVERBIO II, all of which were reported by TCTMD.

Overall, the pooled incidence of definite or probable scaffold thrombosis in the randomized and observational studies was 1.8% at a median follow-up of 1 year and 0.8% beyond 1 year. Compared with the everolimus-eluting stent, Absorb was associated with a higher incidence of scaffold thrombosis at all time points, including early, late, and very late follow-up.

When analyzing data from the randomized trials, the risk of definite or probable scaffold thrombosis within the first year was more than two times greater than with the everolimus-eluting stent (OR 2.59; 95% CI 1.44-4.66). The risk was nearly doubled when the analysis was expanded beyond 1 year (OR 4.81; 95% CI 1.82-12.67).

Similarly, use of Absorb BVS was associated with a relative 63% increased risk of MI within the first year and a 79% higher risk of MI beyond 1 year. Overall, treatment with Absorb was associated with a 31% increased risk of target lesion revascularization and a 37% higher risk of target lesion failure, risks that were evident beyond 1 year.

The bottom line, according to Zhang and colleagues, is that while optimal implantation technique is warranted with Absorb, “better designed scaffolds are needed to improve the clinical outcomes of bioresorbable vascular scaffolds.”

Just last week, a task force from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI) updated their recommendations on the use of bioresorbable scaffolds in clinical practice, ultimately stating the devices have no role over drug-eluting stents given concerns about long-term clinical safety.

For patients who have already received Absorb, one of the major questions pertains to the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy for the prevention of scaffold thrombosis. Although there are no formal recommendations from US or European guidelines, the ESC/EAPCI task force advises that patients currently on DAPT following scaffold implantation should continue with treatment for at least 3 years with Absorb (or the full bioresorption period with other scaffolds). For those who stopped DAPT prior to the bioresorption of the scaffold, a decision to restart treatment should be made on a case-by-case basis after an evaluation of the thrombotic and bleeding risks, they say.

To TCTMD, Stone noted the present report does not include any randomized data beyond 3 years, which is the time point in which the scaffold is completely resorbed. At 36 months, “that’s when we’d hope to start see some benefit for Absorb compared with leaving a permanent metallic frame in the coronary arteries,” said Stone.

Three-year data from ABSORB III and 4-year data from the smaller ABSORB II are scheduled to be presented at TCT 2017 in Denver, CO, as is another meta-analysis with clinical follow-up out to 36 months. Additionally, investigators will present 30-day data on 2,604 patients enrolled in the ABSORB IV study; in that trial, major efforts were made to avoid small vessels, the subset of patients most vulnerable to scaffold thrombosis, said Stone.

“We’ll see the extent to which markedly reducing Absorb implants in very small vessels narrows or eliminates any differences in adverse events between Xience and Absorb, at least within the first 30 days,” Stone said.

Data Could Have Informed Public Debate

In the editorial, Dhruva and Curtis say that US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of Absorb was based largely on 1-year noninferiority data from the ABSORB III study. For Curtis, given the goal of providing patients access to new technologies, the data were sufficient for approval, but he said mandating longer-term follow-up must be part of the approval process.

“I think the FDA’s decision was reasonable,” he said. “The bar of evidence was met, and I think they deserved approval. Going forward, I would look for a very clear and publically transparent plan for how to do surveillance. I think that should include investments, which are already being made, in the apparatus to conduct true effectiveness research in the postmarket sphere.”

The publication of the meta-analysis after Absorb had been pulled from the market also raises another issue, he said. While peer review remains a priority, the long lag time between manuscript submission and publication needs to be shortened so that academic physicians can get their data into the public realm.

“From the public’s perspective, they would want to know that information as soon as it was available, even if it was not yet finalized,” said Curtis. He added that many journal editors are struggling with the potential role of “preprinting,” which would involve publishing early versions of studies before they have been finalized. “It’s a real tension that a lot of journal editors are struggling with . . . but I think this is a discussion that warrants continued input from all stakeholders.”

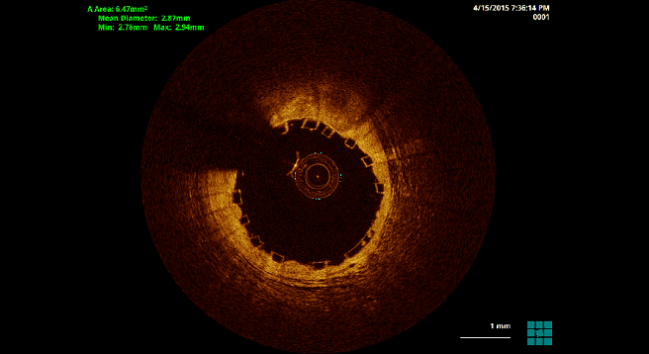

Photo Credit: Ziad Ali

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Zhang X-L, Zhu Q-Q, Kang L-N, et al. Mid- and long-term outcome comparisons of everolimus-eluting bioresorbable scaffolds versus everolimus-eluting metallic stents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:642-654.

Dhruva SS, Curtis JP. Requiem for a scaffold. Ann Intern Med 2017;167:Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Authors report no conflicts of interest.

- Stone is a faculty member of the Cardiovascular Research Foundation, the publisher of TCTMD

- Curtis reports grants from NHLBI, during the conduct of the study; salary support from the American College of Cardiology and Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services; and holds equity in Medtronic.

- Dhruva reports no conflicts of interest.

Comments