AI-Measured Breast Artery Calcification Tied to CV Outcomes in Women

(UPDATED) The incidental mammogram finding isn’t a reason to panic, but it may be a reason to make sure other risk factors are under control.

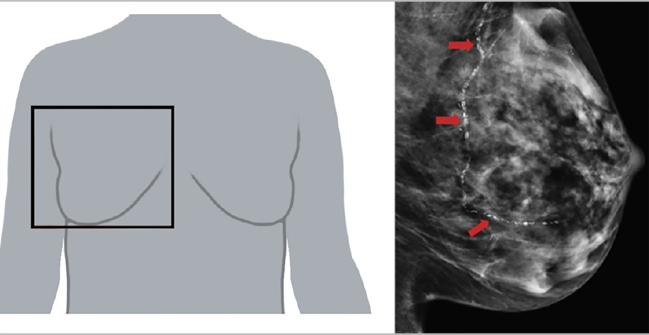

Photo Credit: Adapted from Allen TS, et al. JACC Adv. 2024;3:101283.

Breast artery calcification (BAC) seen on a mammogram is associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes in women, according to a study that quantified the incidental finding using artificial intelligence (AI).

Even after accounting for traditional CV risk factors, BAC was tied to greater risks of all-cause mortality and a composite of acute MI, heart failure, stroke, or mortality, with particularly strong relationships observed in younger women.

This could have implications for personalized CVD risk stratification, researchers led by Tara Shrout Allen, MD, and Quan Bui, MD (both from UC San Diego, La Jolla, CA), suggest in their paper published online recently in JACC: Advances.

BAC being more predictive of adverse outcomes in younger versus older women is a welcome finding, senior author Lori Daniels, MD (UC San Diego), told TCTMD, because “many older women already are at risk or know they're at risk for heart disease merely because of their age or comorbidities. It's the younger women who may not know that they're at risk yet.”

A lot of women start getting mammograms at age 40, so incident BAC is “a good way to pick up risk early on when there's still something we can do about it,” Daniels said, adding, however, that the appropriate response to the finding—whether that’s lifestyle modification, medications, or something else—remains to be determined in future studies.

But in the meantime, she and her colleagues say “the presence of BAC should at the minimum stimulate patient-provider conversations on lifestyle changes to mitigate cardiovascular risk, especially among younger women aged 40 to 59 years.”

Commenting for TCTMD, Ana Barac, MD, PhD (Inova Schar Cancer and Inova Schar Heart and Vascular, Falls Church, VA), who wrote an accompanying editorial with Rupinder Bahniwal, MD (Inova Schar Heart and Vascular), said the presence of BAC “should not convey a signal of panic.”

But she, too, suggested this might be a reason for patients to take a look at their CV risk factors. “BAC is a good reminder for us all to ask a question: whether we know our CV risk factors and whether they are being well controlled,” she said. “So, if you are already seeing the cardiologist or internist, or other physician, and you happen to learn that you have BAC, you should mention it as a reason to review your CV risk factor control and individual goals.”

Incidental BAC on Mammograms

BAC is often seen as an incidental finding on mammograms, and it has been shown to be a marker of increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). “BAC has tremendous appeal for cardiovascular risk stratification because it is noninvasive, comes at no additional cost or radiation, and the majority of women over the age of 40 years already undergo annual screening mammography for breast cancer,” the investigators note.

They add, however, that there is a lack of tools for quantifying BAC and linking that with CV outcomes, and little consensus on how the finding should be detailed on radiology reports.

In the current study, researchers used an automated, AI-based assessment of BAC (cmAngio; CureMetrix) that generates a score of 0 to 100 to indicate the severity of BAC—calcification is considered present when the score is 5 or greater.

The analysis included 18,092 women ages 40 to 90 (mean age 56.8 years) who underwent a screening mammogram at UC San Diego Health between 2007 and 2016. Overall, 40% had hyperlipidemia, 36% hypertension, and 13% diabetes, and 5% were smokers.

BAC was present in 23% of women, with a median score of 15 among those with calcifications. Those with higher BAC scores tended to be older; to have diabetes, hypertension, CVD, chronic kidney disease, or hyperlipidemia; and to be taking statins or antihypertensive medications.

BAC is a good reminder for us all to ask a question: whether we know our CV risk factors and whether they are being well controlled. Ana Barac

The presence of BAC was associated with a higher rate of all-cause death over a median follow-up of 4.8 years (7.8% vs 2.3%) and of the composite outcome over a median follow-up of 4.3 years (12.4% vs 4.3%). After adjustment for potential confounders, differences were significant for both mortality (adjusted HR 1.49; 95% CI 1.33-1.68) and the composite outcome (adjusted HR 1.57; 95% CI 1.42-1.74).

Risks also were increased when BAC score was evaluated as a continuous variable or in quartiles and when patients who were prescribed statins or who had ASCVD at baseline were excluded.

The relationships between BAC and adverse outcomes varied significantly by age, systolic blood pressure, total and LDL cholesterol, smoking, and diabetes (P < 0.001 for all interactions).

Of note, the associations were strongest in the youngest age group (40 to 59 years). After accounting for traditional CV risk factors, BAC correlated with greater risks of mortality (adjusted HR 1.51; 95% CI 1.22-1.87) and the composite outcome (adjusted HR 1.52; 95% CI 1.25-1.85) in this age group. The relationships were weaker but still significant among women ages 60 to 74 years, losing statistical significance among women ages 75 and older.

“Results from this study and others suggest that BAC may develop at an earlier age than other traditional cardiovascular risk factors, and thus could serve as an early biomarker of underlying ASCVD risk,” the researchers say. “These findings are important since they suggest that early risk stratification with BAC in younger women may help identify new candidates for lifestyle modification and preventative therapies and may ultimately help improve their outcomes.”

Questions Remain

Though the presence of BAC may aid in risk stratification, many questions remain, Barac indicated, noting that the link between outcomes and breast calcification hasn’t been as systematically studied as for coronary artery calcifications, for instance.

One piece of information that is missing from the current study is the association of BAC with cause-specific mortality, Barac said. She commended the researchers, however, on their scientific approach to studying the impact of BAC, which should be considered, for now, as a “finding,” not a “disease.”

“The emerging evidence, including the evidence from this study, is that they are associated with cardiovascular risk factors and events such as stroke, heart failure, and cardiovascular disease,” Barac said.

But BAC is a finding for which there is no proven course of action. “We do not have evidence that treating something is going to improve the outcomes,” Barac said. “We are just finding these patients may be at increased risk. We don't fully understand what that risk is.”

Another major question, she indicated, is how incidental BAC should be reported. “I think it's a big deal that we do not have standards for reporting BACs because this will result in a huge discrepancy. This is something that the American College of Radiology should have for physicians interpreting and reporting mammograms.”

When BAC is reported, it should spark some thought about CV risk factor control, she reiterated. “You should be seen and be treated for, for example, blood pressure,” Barac said.

So many women get mammograms every year, and there's information there that can help them assess their risk essentially for free. Lori Daniels

What’s not clear is whether BAC might one day achieve the status of a risk enhancer. Other unrelated research has identified factors like family history, genetics, or pregnancy complications that elevate future ASCVD risk, warranting more aggressive risk factor control.

“Right now on the basis of these findings, I don't have data to say that we should treat a person's blood pressure or cholesterol to a different goal compared to somebody who doesn't have calcifications,” said Barac.

Moving forward, Daniels said, it would be reasonable for radiologists to start reporting incidental BAC when it’s seen on mammograms, so that research can continue into the significance of the finding and how the associated cardiovascular risk might be modified, similar to the process that occurred with the systematic evaluation of coronary artery calcification as a risk factor.

“The main reason I'm excited about this is because this data is sitting there and so many women get mammograms every year and there's information there that can help them assess their risk essentially for free,” she said. “If it were me and I had that risk factor sitting there, I would want to know it probably even before it's 100% proved that early intervention could improve outcomes.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Allen TS, Bui QM, Petersen GM, et al. Automated breast arterial calcification score is associated with cardiovascular outcomes and mortality. JACC Adv. 2024;3:101283.

Barac A, Bahniwal RK. My AI-assisted mammography report says “breast artery calcifications.” Should I see a preventive cardiologist? JACC Adv. 2024;3:101288.

Disclosures

- This research was in part funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

- Daniels reports having served as consultants to CureMetrix.

- Allen, Bahniwal, and Barac report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments