Antihypertensives Cut CV Events Across BP Levels, Regardless of Prior CVD: BPLTTC

The findings will no doubt add energy to a long-running debate about blood pressure thresholds and risk/benefit trade-offs.

Antihypertensive therapy to reduce blood pressure cuts the risk of cardiovascular events even in people with no prior heart disease and in people with normal baseline systolic blood pressure, a massive international meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials suggests. The larger the drop, the greater the impact in reducing major cardiovascular events.

The findings will no doubt add energy to a long-running debate about thresholds for hypertension diagnosis and treatment, particularly whether BP-lowering might help prevent events even in patients with lower baseline levels—not to mention whether recommendations should differ for primary and secondary prevention.

“The decision to prescribe blood pressure-lowering medication should not be based simply on a prior diagnosis of cardiovascular disease or an individual’s current blood pressure. Treatment works equally well in those with or without cardiovascular disease and irrespective of baseline blood pressure,” said Kazem Rahimi, MD, DM (University of Oxford, England), who presented the Blood Pressure Lowering Treatment Trialists Collaboration (BPLTTC) analysis during the virtual European Society of Cardiology Congress 2020 today. “Rather, antihypertensive medications are best considered as risk-modifying treatments for prevention of incident or recurrent cardiovascular events, regardless of blood pressure values at baseline.”

Antihypertensive medications are best considered as risk-modifying treatments for prevention of incident or recurrent cardiovascular events, regardless of blood pressure values at baseline. Kazem Rahimi

Various professional society guidelines differ in their recommendations as to when blood pressure-lowering therapies should be initiated, with European guidelines recommending that treatment is warranted for systolic BPs over 140 mm Hg and US guidelines recommending a lower cut point of 130 mm Hg, Rahimi noted in an online press conference. Recommendations also differ in various jurisdictions according to patient age, comorbidities, and whether or not they have preexisting cardiovascular disease.

A Mega-Analysis

The BPLTTC analysis combined individual patient-level data from 48 randomized clinical trials that had a minimum of 1,000 patient-years of follow-up and that compared different drug classes (either head-to-head or against placebo) or more- versus less-intensive drug regimens. Ultimately, a total of 348,854 individual patients were included, “making it the largest analysis of its kind,” Rahimi said.

Patients were grouped according to whether or not they had a prior diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, then further stratified according to one of seven blood pressure groups ranging from systolic BPs of < 120 mm Hg up to ≥ 170 mm Hg.

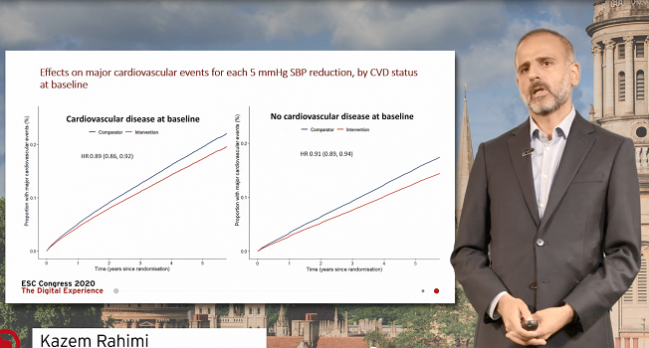

As Rahimi showed during his Hot Line presentation today, for every 5-mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure due to antihypertensive treatments, patients both with and without preexisting cardiovascular disease at baseline had similar, progressive benefits over 5 years of follow-up. “Presence or absence of cardiovascular disease at baseline did not play a role in terms of determining the relative risk reductions for the composite endpoint of major cardiovascular events observed across those trials,” he said.

At the end, it is a balance of the benefits and the side effects that will make the decision. Hans Reitsma

In secondary analyses looking at individual CV outcomes, there was no evidence of a difference in the reduction of stroke, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, or cardiovascular death due to blood pressure-lowering, based on prior CVD diagnosis.

Moreover, in an analysis stratifying results according to both prior CVD or no CVD as well as the seven different categories of baseline systolic blood pressure, the reduction in major cardiovascular events associated with every 5-mm Hg reduction in systolic blood pressure was similar across all of the groups.

“This study shows that the relative effect of blood pressure-lowering treatment is proportional to the intensity of systolic blood pressure reduction, and each 5-mm Hg reduction of systolic blood pressure reduces the risk of major CVD events by 10%, stroke by 13%, heart failure by 14%, ischemic heart disease by 7%, and cardiovascular death by 5%,” Rahimi concluded. “There was no evidence that the proportional effects varied by baseline blood pressure values, down to the lowest systolic blood pressure category of < 120 mm Hg, in both the primary and secondary prevention settings.”

Discussing the results during the press conference yesterday, Rahimi said he believes they should impact clinical practice.

“[The results] question the widely held view among clinicians and policy makers that prior disease as well as blood pressure itself are key determinants of treatment decision-making,” he said. “What this study shows is clear evidence against that assumption and that should hopefully simplify the guidelines. It should take those determinants out of the equation as individual components of decision-making and [convince physicians to] look more widely at cardiovascular disease. In other words, it in a sense makes the case for not withholding treatment from people simply based on their blood pressure or prior disease status.”

Unanswered Questions

Discussing the BPLTTC analysis following Rahimi’s presentation, Hans Reitsma, MD, PhD (University Medical Center, Utrecht, the Netherlands), offered a review of the overarching strengths and shortcomings of patient-level analyses of this size, but noted that for the specific and provocative conclusions reached by the investigators, there are “some questions still to be answered.”

A key component, he said, will be shared decision-making with patients about initiating blood pressure-lowering treatments. Another is the need to focus on absolute treatment effects rather than relative benefits. “We need also more independent analyses to obtain such estimates for individual patients and we need more data on side effects,” Reitsma added, “because at the end, it is a balance of the benefits and the side effects that will make the decision.”

Adherence to treatment is also an important factor to consider, Reitsma added.

In the live, online Q&A following Rahimi’s presentation he clarified that he and his co-investigators have not yet done analyses stratified by age or sex—contentious topics in the sphere of blood pressure-lowering—nor have they looked at the consistency of blood pressure-lowering across different drug classes. This is something, Rahimi said, that previous studies have done.

“We do expect there to be some differences between drug classes—there have been reports, for instance, that calcium channel blockers might be less effective at the prevention of heart failure whereas they tend to be stronger for stroke. And on the other side, the reverse might be true for diuretics,” Rahimi said. “We are well aware of some of those subtle differences, but what we did here, in a sense, was scaled the effect of blood pressure-lowering across the different classes to answer the question of whether the blood pressure threshold itself and the presence or absence of cardiovascular disease have got any effect on treatment modification.”

If someone is very young and hasn’t got major comorbidities or cardiovascular risk factors, . . . the absolute gain obtained in that sort of population is going to be lower. Robert Carey

Robert Carey, MD (University of Virginia, Charlottesville), who was vice chair of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) hypertension guidelines, commented on the analysis for TCTMD. He congratulated the BPLTTC investigators, whom he called “a very reputable study group,” for their very rigorous analysis.

“I think that the study, which is quite large and with individual patient data, really supports the 2017 ACC/AHA guidelines,” Carey said. At the time the guidelines were being drafted, a number of much smaller meta-analyses hinted there would be a benefit even in people without hypertension or at lower baseline blood pressure levels. “That resulted in our dropping the threshold for hypertension to 140/90 mm Hg to 130/80 mm Hg, and also dropping the recommendation for BP-lowering from its previous level of 140/90 mm Hg to its current level of 130/80 mm Hg.”

A couple of important questions remain, Carey continued. “When you are giving antihypertensive medication to a person with perfectly normal blood pressure, are you inducing any harm or any serious adverse side effects such as hypotension, or falls, or kidney injury? To my knowledge these presentations don’t answer that question, so that would have to be worked out.”

While the top-level findings support the lower-is-better approach advocated in the 2017 guidelines, he continued, “I think we’re going to need prospective randomized clinical trials that specifically target this issue of giving antihypertensive medications to people with normal blood pressure to make sure that the efficacy and safety are really there,” Carey said. “This is a good meta-analysis, it’s a good hypothesis-generating study, but I don’t think it will by itself change the guidelines. I think were going to need some additional work.”

Healthy Advice

As a final point, Carey emphasized that the 2017 guidelines place a lot of emphasis on lifestyle modifications. Extrapolating from BPLTTC results, he said, it’s possible that some of the benefits suggested by this analysis could be achieved without medication, particularly in people who don’t currently meet the definition of being hypertensive.

Indeed, one point stressed by Rahimi during yesterday’s press conferences is that study conclusions should not imply that everyone, even in the absence of CV risk factors, would benefit from blood pressure therapy. After all, the patients included in BPLTTC study all had indications for being enrolled in trials in the first place.

“One should not draw the conclusion that everyone should be receiving treatment,” he stressed. “There are other reasons why treatment should or should not be initiated. That includes obviously the absolute risk that an individual has of suffering cardiovascular disease. If someone is very young and hasn’t got major comorbidities or cardiovascular risk factors, despite the fact that the proportional effect that they’d get from treatment would be very similar to someone who has severe risk factors, obviously the absolute gain obtained in that sort of population is going to be lower.”

There would also be economic, drug tolerance, and drug safety factors to consider, he added.

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full BioSources

Rahimi K. Pharmacological blood pressure-lowering for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease across different levels of blood pressure. Presented at: ESC 2020. August 31, 2020.

Disclosures

- BPLTTC was supported by grants from the British Heart Foundation, Oxford Martin School, NIHR Oxford BRC, UK Research and Innovation, and Sensyne Health.

- Rahimi and Carey report having no conflicts of interest.

Comments