Country Roads: Vulnerable West Virginia Heart Patients Targeted in Outreach Program

The humanitarian effort is designed after similar programs in India and China, the goal being to get neglected patients screened by a cardiologist.

Earlier this month, a team of 16 sonographers and four cardiologists volunteered their time and expertise to participate in a humanitarian outreach program designed to screen and immediately diagnose cardiovascular disease in patients with limited access to diagnosis and prevention. The daylong screening program did not take place in a remote, underserved corner of the globe, however, but in rural West Virginia, one of the poorest states in the US and one hit particularly hard by the opioid epidemic.

The project, known as CHOICE 2018, saw 374 patients screened in four West Virginia cities over 7.5 hours using several point-of-care technologies, including portable ultrasound and ECG screening. The 20 providers, joined by teams of technologists- and physicians-in-training, performed 1,152 diagnostic tests.

Framed as an outreach effort to access parts of the state where patients either lack health insurance or face high out-of-pocket costs, the team detected moderate or severe cardiovascular disease requiring immediate triage in roughly 8% of the patients screened. In some instances, the teams saw patients with ejection fractions as low as 10% or 15%. In one symptomatic patient, they identified critical aortic stenosis and this led to a call to a surgical team for an immediate consultation.

“I thought when the patients arrived we’d have complete chaos, but it all went very efficiently,” said project leader Partho Sengupta, MD (West Virginia University Heart and Vascular Institute, Morgantown). “And the amount of the information—it’s wasn’t just any visit. I was very pleased by how much information we collected.”

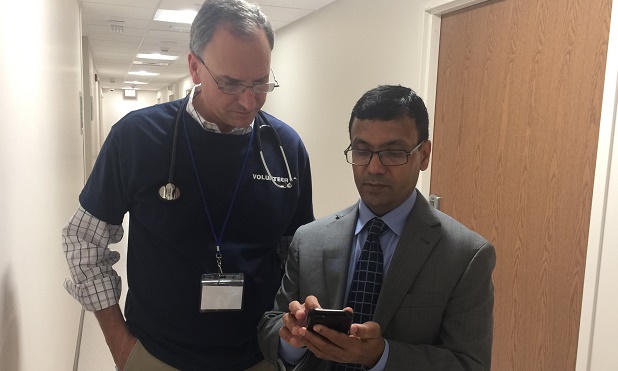

Neil Weissman, MD (MedStar Health Research Institute, Washington, DC), and Partho Sengupta, MD (WVU Medicine, Morgantown) review images streamed from one of the West Virginia sites.

Six years ago, another group of cardiologists, sonographers, and engineers participated in a global outreach program to screen more than 1,000 men and women living in a far corner of India using a portable point-of-care ultrasound. Images from Sirsa, a city located some 250 km northwest of Delhi, were uploaded to the cloud and then read by clinicians in 75 different countries.

That gargantuan effort was also led Sengupta, then an associate professor and director of ultrasound research at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, NY), and was so successful that it spurred additional humanitarian efforts to reach largely rural communities. Since 2012, the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) has been involved in cardiovascular screening programs in China, Vietnam, Argentina, Kenya, the Philippines, and Cuba, among other countries, where access to medical care and advanced technology is also limited.

Speaking with TCTMD, Sengupta said their goal was to take what they had learned overseas and apply it back home to parts of the country where access to cardiovascular care is lacking.

“There are lots of patients in belts where physician access is critical,” said Sengupta, referring to large swaths of West Virginia. “So many people travel 2 or 3 hours from the mountains to their providers.” There are also clinical scenarios unique to the state, something physicians don’t yet understand. Cardiovascular patients, for example, are younger in West Virginia than in other parts of the country, said Sengupta, noting he often sees people with MI who are just 30 or 40 years old. Whereas patients with severe aortic stenosis might not present until their 80s elsewhere, Sengupta says they are frequently treating these patients when they’re just 60 or 70 years old.

West Virginia is an Appalachian state and many patients treated at WVU Medicine, the state’s largest medical provider, are on Medicare or Medicaid. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, heart disease is the leading cause of death in West Virginia and the state has one of the country’s highest age-adjusted mortality rates from cardiovascular and coronary heart disease. One in four West Virginians smokes, and obesity is rampant.

“We are a state that has not thrived in the postindustrial revolution,” said Clay Marsh, MD, vice president and executive dean for health sciences at WVU Medicine. “We have sort of been left behind.”

We are a state that has not thrived in the postindustrial revolution. Clay Marsh

Sengupta, said Marsh, is a “wonderfully gifted” young physician leader and was recruited to WVU based on his broad interest in new technology for improving the health of his patients and the community at large. “It’s his energy and vision that brought people from all over the country to really launch this humanitarian effort across the state, to reach the people that might not have access to the kind of sophisticated care or screening that we were able to do through this project,” Marsh told TCTMD.

Partnered With ASE Foundation

The West Virginia effort was conducted in collaboration with ASE and various industry partners, including a grant from Edwards Lifesciences Foundation. The ASE Foundation, a charitable group attached to the society, was incorporated in 2003 and their goal has been to support patient care and to increase awareness about cardiovascular disease, said Robin Wiegerink, chief executive officer of ASE. “We wanted to do something in the United States, but the way the medical systems work we really needed to partner with a medical institution who was willing to provide the doctors, the infrastructure, and the framework to do it,” she told TCTMD.

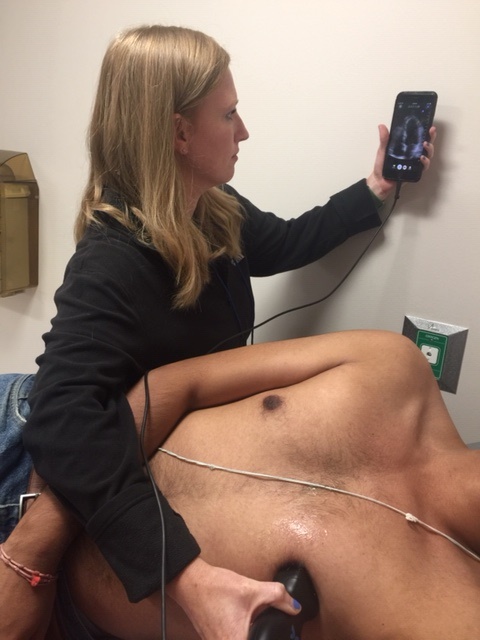

On October 20, 2018, Sengupta and colleagues screened individuals in Morgantown, Fairmont, Bridgeport, and Elkins using the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared Kardia mobile ECG monitor (Alivecor), a pocket-sized portable ultrasound (Butterfly IQ), and a device that measures and records vital signs (CloudDX), such as blood pressure, weight, oxygen saturation, heart rate, and respiration. A full, advanced cardiac ultrasound platform (Hitachi) also was available, and physicians performed 27 additional tests on patients in whom they found significant abnormalities. On-site genomics testing (Phosphorus) was provided to understand the genetic underpinnings of the identified cardiac abnormalities, while a digital platform (Kencor Health) was used to facilitate patient engagement and ensure appropriate follow-up.

By using the point-of-care tools, Sengupta said they were better able to make appropriate use of downstream testing. In clinical practice, roughly half of patients seen in clinic are taken for a full ultrasound or other advanced cardiac tests, he noted, adding that they are studying whether such point-of-care diagnostic modalities can lead to more precise and cost-effective tests.

“Once the testing was done, the patient went to the provider where the consultation was done and then the patient would be advised as to what next steps would be required,” said Sengupta. He stressed the immediacy of the consult was critically important to the success of the project. “The idea was that the patient comes in and you give them an answer right away with full confidence. My philosophy is that many patients are coming from a long way and you’re going to see them for 15 minutes. You need to have the conviction and confidence to develop the physician-patient relationship. If you don’t have conviction at the point of care, the patient is going to have a lot of questions.”

Moreover, if these individuals were sent home after screening without a consultation, many simply wouldn’t have returned for a later visit. “I’ve had patients where we order tests but they never come back and they’re dying somewhere,” said Sengupta. “By the time they’re seeking a doctor, they are in advanced stages. They’ve waited and they’re symptomatic. We need to be able to triage them very efficiently.”

I’ve had patients where we order tests but they never come back and they’re dying somewhere. Partho Sengupta

When the teams gathered the next day to debrief on the success of the project, Sengupta said everybody had a story about a high-risk case they identified. The researchers are still collecting data and plan to publish their full results as soon as possible.

“Events like this where we use new technology allows us to see the disease in new ways,” said Sengupta. “It’s one of the interests I have—what is happening here that is different [than outside the state] and how can we address it? Obviously, it’s a big burden and we need to address the subclinical disease. It’s too late when somebody comes in with a heart attack or stroke. I need to see valvular heart disease at an earlier stage. If we could somehow preempt that then we wouldn’t have to spend millions of dollars dealing with late interventions.”

Difficult Travel in Wintertime

The largest city in West Virginia, Charleston, has just 55,000 people, and Morgantown, the home of WVU, has a population just a shade over 30,000. Although the towns where screening took place aren’t excessively far from the main WVU Medicine campus, travel in the wintertime can be difficult, said Marsh. Calling the program a “tremendous success,” Marsh pointed out that the goal was to “reach people who might be isolated or who might not have access—for a variety of reasons—to the technology or these kinds of experts.”

Allan Klein, MD (Cleveland Clinic, OH), a past-president of ASE who was not involved in the outreach program, noted that while there have been several humanitarian efforts to reach at-risk populations abroad, there are many underserved areas in the US that could benefit from point-of-care ultrasound examinations. In 2014, the ASE Foundation participated in a free medical program for those living in LA County, with eight physicians and nine sonographers performing consults on 130 patients over a 4-day period.

The Cleveland Clinic, he noted, is frequently referred patients from West Virginia because they have such advanced disease when they first come into contact with the medical system. “So, what Dr. Sengupta is doing is really great, because they’re reaching people in their own backyard who don’t have access or aren’t going to the doctor for whatever reason,” Klein told TCTMD.

Wiegerink added that patient awareness about risk factors and cardiovascular health is not ideal either. “The American Heart Association does a great job, and a lot of organizations have done a lot of work to increase awareness, but the bottom line is that people still have little awareness of their own heart health,” she said. “Getting people to come in and get checked out is difficult.”

Some people tested didn’t initially intend to be screened, noted Wiegerink. They had volunteered to drive a parent or spouse to the event, or were simply visiting their kids at WVU, but ended up under the proverbial microscope. One of the most severe forms of cardiac disease she saw during the screening initiative was diagnosed in a 26-year-old male. “It wasn’t congenital heart disease either,” said Wiegerink. “This is not something they would have had as a baby.”

Some people tested didn’t initially intend to be screened, noted Wiegerink. They had volunteered to drive a parent or spouse to the event, or were simply visiting their kids at WVU, but ended up under the proverbial microscope. One of the most severe forms of cardiac disease she saw during the screening initiative was diagnosed in a 26-year-old male. “It wasn’t congenital heart disease either,” said Wiegerink. “This is not something they would have had as a baby.”

Overall, Sengupta believes in these point-of-care technologies and said the patients screened were very satisfied with the event. He was initially worried the density of clinical information might overwhelm some individuals, but the opposite occurred and it strengthened the relationship between patient and physician. “People see their ultrasound, and they know we have factual evidence of what we’re talking about,” he said. “It gives them confidence that what I’m telling them is true. They believe you.”

This is particularly important because chronic disease has a massive behavioral component, he stressed. If you don’t have conviction in the diagnosis—which is enabled with these portable, point-of-care technologies—how can a patient be compliant? “They need to have an understanding that this is going to work for them,” said Sengupta.

In his clinical practice, Klein uses point-of-care ultrasound as an extension of his physical exams. With portable ultrasound, physicians get a “pretty good assessment” of the anatomy of the heart and its overall performance, as well as valvular function more specifically. “It’s not a full-practice echo, it’s a focused echo assessing the immediate problem, for example, valve regurgitation, but the images with some of the newer machines are quite good and diagnostic,” he said. Also, Klein added, patients appreciate that they can see the immediate problem and they love the technology.

The entire project, which included co-project leader Sanjeev Bhavnani, MD (Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, CA), was approved by the WVU institutional review board because the team designed a cluster, randomized trial within the daylong project. As part of the project, they had the patients meet the technologist first and then the physician provider and then the other way around. The goal was to determine how the physicians and patients interact with each other, and whether this impacts clinical outcomes and/or the efficiency of the information exchange. The goal of the trial within the outreach program was to determine what “this means for traditional cardiovascular medicine,” said Sengupta.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Sengupta reports consulting for HeartSciences and Ultromics and research grants from HeartSciences, Hitachi, EchoSense and Genetesis.

Comments