Gray but Happy: Cardiologists Report High Career Satisfaction, With Some Red Flags for Women

It’s time to fix disparities, one expert says. There are simply not enough white men to treat heart disease in the decades to come.

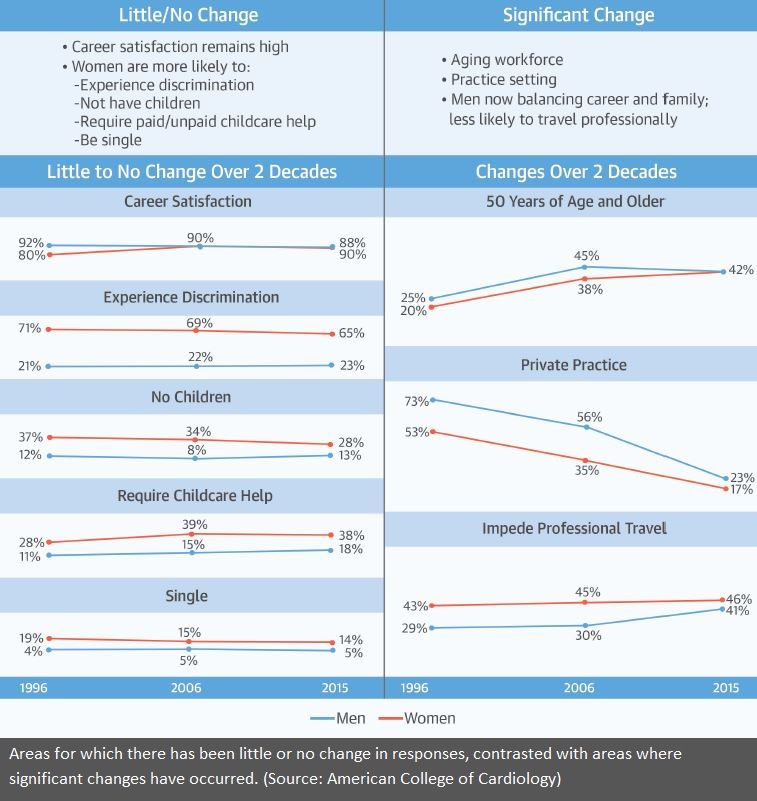

A new survey conducted in more than 2,000 cardiologists reveals that while there have been some important professional shifts in this demographic over the last two decades, cardiologists remain highly satisfied with the career they’ve chosen.

Disturbingly, however, female cardiologists report significantly more discrimination on the job and, at least on the surface, appear to be making different personal life choices—a hint that having a family and a cardiology career is harder for women than men.

“To me, the critical thing is to look at the results over time,” senior author of the survey results, Claire S. Duvernoy, MD (Ann Arbor Healthcare System, University of Michigan), told TCTMD. “So while some things have changed, I think what is really striking is that many things have not changed that much, and that is both disappointing and maybe not that surprising.”

Results from the American College of Cardiology’s third Professional Life Survey were published online today in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

High Satisfaction but Some Signals of Concern

The Professional Life Survey has been conducted every 10 years for the last three decades and this year was completed by 2,313 cardiologists, of whom 42% (964) were women. While the survey was initially launched to gauge the impact of an apparent pending shortage of cardiologists, it was always intended to take the pulse of career satisfaction among women and men. In 2006, the survey also incorporated questions aimed at understanding the underrepresentation of women and minorities as “a critical workforce issue.”

For the 2015 survey, questions were geared towards understanding whether efforts by the College as well as ongoing societal shifts were helping to close some of the gender gaps in cardiology. Response rates to this year’s survey, which was sent to 8,821 cardiologists, were 30% for women and 18% for men.

Among the key findings:

- Career satisfaction is high: 90% of men and 88% of women reported being moderately to very satisfied with their work lives.

- Men were more likely than women to work in interventional cardiology (23% vs 8%; P ≤ 0.001) and electrophysiology (10% vs 6%; P ≤ 0.01 for both).

- Cardiologists practicing today are older than in previous decades, with a significantly greater percentage being 60 years or older in the current survey results as compared with in 2006 or 1996.

- Roughly two-thirds of men and women are satisfied with their level of compensation, with women reporting slightly lower levels of satisfaction. Women, however, are more likely than men to feel they are not advancing in their fields.

- More than two-thirds of women say they experience discrimination at work, and while that proportion has declined since 1996, it remains three times higher than the rate of discrimination reported by men.

- Men were more likely to be married (89% vs 75%), more likely to have children (87% vs 72%), and more likely to have spouses that provided all childcare (57% vs 13%, P ≤ 0.001 for all).

- Women were more likely than men to say that family responsibilities had a negative impact on their career advancement (37% vs 20%; P ≤ 0.001).

- Women were more likely than men to work in pediatric cardiology (13% vs 7%), to practice part-time (10% vs 5%), and to spend time in research and teaching (14% vs 10%, P ≤ 0.001 for all).

- Respondents overall were less likely to practice invasive noninterventional cardiology in 2015 versus 1996.

Some Things Change, Some Things Stay the Same

Speaking with TCTMD, Duvernoy pointed to things that have “changed a lot”—in particular, there has been a shift away from private practice and into employment settings. The aging demographic is also important, she said. “We’re getting older. That has huge implications for who is going to take care of patients with heart disease 10 and 20 years down the road.”

We can’t rely on white men to do the job, because there are simply not enough white men. Claire S. Duvernoy

Part of that, she acknowledged, is that training times are lengthening. “There is more and more to learn and that may add more and more time to training, but I also think that if we continue to have a lack of diversity and a lack of women in our field then we are losing out on all those people in our population,” Duvernoy said.

Two-thirds of respondents in the 2015 survey identified themselves as white. “So we really need to tap into women and the minorities that are underrepresented in cardiology,” she suggested. “We can’t rely on white men to do the job, because there are simply not enough white men.”

Duvernoy also underscored the ways in which lives lived by men and women in cardiology are not the same, pointing specifically to the high rates of reported discrimination among women, typically around sex and parenting. “We have to figure out how to fix that,” she said.

The numbers that illuminate the home lives of men and women are also provocative, with women much less likely to have spouses or families. “Far be it for me to prescribe life choices that people are making,” Duvernoy said, “but I do think there is an underlying sense, looking at this data, that that doing this job and having a family is harder when you are a woman.”

While this survey did not capture data on compensation differences, other recent studies have documented a wage gap, even after adjusting for different specializations in cardiology and for full- and part-time work. Duvernoy believes compensation disparities are likely a “deterrent” to women going into cardiology, although the issue is by no means limited to this field.

Hopefully we can show young women that it is possible to do this, that it’s possible to have a great career. Claire S. Duvernoy

So how can certain gaps be closed? “I think knowledge is always the first priority and putting this knowledge out there will help in and of itself,” Duvernoy told TCTMD. She also pointed to efforts by the Women in Cardiology Council, which conducted the survey and is working with the College, the American Heart Association, cardiology program directors, and leadership in both the academic and private practice settings to take concrete steps to make the profession more welcoming to women.

“Hopefully we can show young women that it is possible to do this, that it’s possible to have a great career,” she said. “Our results show people in cardiology love their job, whether you are a woman or man, and that applies to me and everybody I know in this field.”

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full BioSources

Lewis SJ, Mehta LS, Douglas PS, et al. Changes in the professional lives of cardiologists over 2 decades. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016:Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Disclosures: Authors report having no conflicts.

Comments