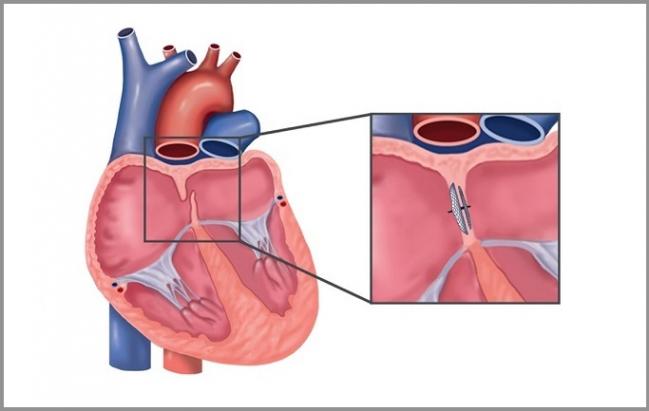

Late Follow-up of PFO Closure for Stroke Raises Questions for Antiplatelet Duration

PFO closure looked to be safe and effective long-term in this single-center series, but with the hole plugged, do patients still need aspirin?

Long-term follow-up of patients who underwent patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure for cryptogenic stroke points to a very low rate of ischemic events and no device safety issues emerging beyond 10 years, according to a new analysis. Whether patients should be taking prolonged antiplatelet therapy—and for how long—remains unclear: in the current study, one in five patients stopped their antithrombotic with no adverse consequences, while bleeds were seen in patients who stayed on their meds.

“Long-term data is always important, but I would say in this particular group of patients, which are young patients, it’s even more important because this is a population that is going to live for many years after the initial event,” senior author Josep Rodés-Cabau, MD (Quebec Heart and Lung Institute, Quebec City, Canada), told TCTMD. “I think that it was important to have that data beyond 10 years in terms of safety and efficacy of the implanted device and in fact, it seems to be quite clear. This extends the observations of the randomized trials beyond 10 years and up to 17 years of follow-up, showing that really the rates of recurrent ischemic events are extremely low.”

Only in recent years has the tide of evidence changed in favor of PFO closure for cryptogenic stroke, based on positive results from three randomized controlled trials that were many years in the making—RESPECT, CLOSE, and REDUCE. All three were published in September 2017, prompting a number of new position papers and “rapid recommendations” supporting a role for PFO closure plus antiplatelet therapy over antiplatelet therapy alone in patients with cryptogenic stroke for whom anticoagulation is not an option.

In the years since the earliest PFO studies began, however, countless patients have been treated off-label or as part of clinical studies, and the long-term safety and efficacy in this group remains unclear. Rodés-Cabau and colleagues, including first author Jérôme Wintzer-Wehekind, MD (Quebec Heart and Lung Institute), offer some insights from a single-center series in their paper published online ahead of the January 29, 2019, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Looking Over the Longer Term

The series includes 201 consecutive patients who had their PFOs closed between 2001 and 2008. Information on ischemic and bleeding events, plus use of antithrombotic therapy, was available out to a median of 12 years and ranged from 10 to 17 years.

In all, 13 patients died over the follow-up period, although none of the deaths were cardiovascular. Two patients had nondisabling strokes and six patients had transient ischemic attacks (TIAs). Bleeding events were more common, occurring in 13 patients; major intracranial bleeding was seen in four patients, all of whom were taking aspirin at the time of their event.

Speaking with TCTMD, Rodés-Cabau stressed that there were no other major, late complications that have been raised as potential problems in shorter follow-up—device erosion or pericardial tamponade. “We didn’t see anything like that in our population,” he said, adding that longer-term follow-up of the three RCTs have also not seen these complications. “We knew there was some concern about these late events, but in general I would say it's very rare [although] I'm not saying that they do not exist.”

Case series that have included these types of problems typically also included larger atrial septal defect closure procedures, where device placement may increase the risk of events. Experimental studies have also demonstrated very good endothelization of PFO devices within the first 3 to 6 months, which would mitigate the risk of erosion, he added.

A more pressing concern for Rodés-Cabau and his co-authors stems from an exploratory analysis in their series showing that at last follow-up 20% of patients had stopped all antithrombotic therapy, typically around the 6-month mark. No ischemic or bleeding events occurred in this subset of patients; by contrast, among patients still taking antithrombotic treatment, seven had had a stroke or TIA and nine had experienced a bleed. All of these patients were taking aspirin, and three of them were taking aspirin plus clopidogrel.

“It's not clear what to do with antithrombotics in many of these patients, especially the youngest ones with no other risk factors, no hypertension, no tobacco use, no diabetes,” Rodés-Cabau observed. “For many of these patients—say, a 32-year-old patient— the question they have after closure is: do I have to take this pill for life? And we don't have a clear response. As we say in the study, there are some guidelines talking about 5 years and others recommending lifelong antithrombotic therapy, but I think it's an interesting message and somewhat provocative in our study that we have more bleeding events than ischemic events.”

Needing a Rethink

Indeed, in an accompanying editorial, Bernhard Meier, MD (University Hospital of Bern, Switzerland), a longtime champion of PFO closure, along with Fabian Nietlispach, MD, PhD (University Hospital of Zurich, Switzerland), zero in on the bleeding risk.

“For the first time, we learn that continuing even only acetylsalicylic acid confers a bothersome risk for bleeds without protecting against anything, once the prime culprit, the PFO, has been taken care of,” they write. “Neurologists generally insist on permanent antiplatelets even in otherwise healthy patients with a stroke, subsequent PFO closure, and no atherosclerosis present or even at the horizon, a prerequisite for calling the stroke cryptogenic or naming it embolic stroke of undetermined cause (ESUS) and recommending PFO closure. They will have to rethink that, as they will have to rethink calling a stroke in the presence of a PFO cryptogenic or ESUS.”

Meier and Nietlispach’s editorial goes on to call for guideline changes, making PFO closure a first-line therapy for secondary stroke prevention, but—more provocatively—also suggests that the closure of a PFOs, when discovered, should be considered for the primary prevention of stroke.

The conclusions of Rodés-Cabau and colleagues are much more circumspect, drawing reassurance from the long-term safety and efficacy data and suggesting that a shorter duration of antiplatelet therapy after closure might be “a safe option, to be evaluated in future studies.”

Photo Credit: Adapted from Wintzer-Wehekind J, et al. Long-term follow-up after closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with cryptogenic embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:278-287. Used with permission.

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full BioSources

Wintzer-Wehekind J, Alperi A, Houde C, et al. Long-term follow-up after closure of patent foramen ovale in patients with cryptogenic embolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:278-287.

Meier B, Nietlispach F. Device closure of the patent foramen. The longer you look, the more you like it. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:288-290.

Disclosures

- Wintzer-Wehekind reports receiving grant support from the Association de Recherche Cardio-vasculaire des Alpes.

- Rhodés-Cabau reports holding the Canadian Research Chair, Fondation Famille Jacques Larivière, for the Development of Structural Heart Disease Interventions.

- Meier reports receiving speaker and proctor fees from Abbott.

- Nietlispach reports receiving speaker and proctor fees from Abbott, Edwards, and Medtronic.

Comments