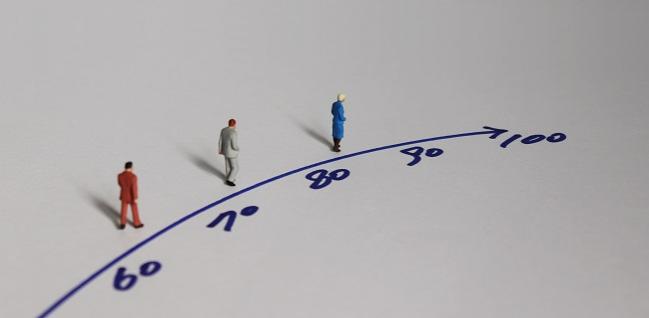

Life Expectancy Post-SAVR Varies by Age, Raising Questions for Treatment Timing

Knowing more about survival rates can help inform decision-making for physicians and patients, experts say.

Patients with severe aortic stenosis (AS) who undergo surgery to treat their condition still have a far lower life expectancy than their peers in the general population, an analysis of Swedish registry data shows. But there are important variations related to age, such that younger patients are more vulnerable to dying earlier, whereas older patients come much closer to matching the survival of individuals who haven’t undergone SAVR.

“Our study adds information about the life expectancy after SAVR, which is important for both physicians and patients before and after SAVR,” lead author Natalie Glaser, MD, PhD (Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden), said via email. “It was surprising that the decrease in life expectancy was so pronounced in younger patients, and comparable to the life expectancy in patients diagnosed with breast or prostate cancer.”

In no way should these results—published online ahead of the July 9, 2019, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology—discourage treatment, however. As Glaser reminded TCTMD, “Without surgery, the prognosis of severe aortic stenosis is extremely poor. Therefore, the life expectancy with surgery is much better, even though it may not be as high as for the general population, at least not in younger patients.”

As noted by Andras P. Durko, MD, and Arie Pieter Kappetein, MD, PhD (both from Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands), in an accompanying editorial, information about survival can be used to “adequately inform patients and physicians before making decisions regarding treatment strategy.”

SWEDEHEART Data

Glaser et all focused their investigation on 23,528 patients in the SWEDEHEART registry who underwent primary SAVR with or without CABG surgery between 1995 and 2013. They matched these individuals by age, sex, and year of surgery to others in the general Swedish population. Mean follow-up duration was 6.8 years (maximum 19.2 years).

Relative survival between the SAVR and non-SAVR groups was used to estimate cause-specific mortality. Over the years, patients who underwent SAVR had consistently lower survival than people in the general population.

Long-term Survival Rates

|

|

5 Years |

10 Years |

15 Years |

19 Years |

|

SAVR Patients |

80% |

55% |

32% |

21% |

|

General Population |

82% |

62% |

44% |

34% |

|

Relative Survival |

97% |

88% |

73% |

63% |

“Expressed in terms of mortality, at 19 years after AVR, 37% of the patients would have died of causes associated with, or due to, AVR,” the researchers explain. “The clinical interpretation of this hypothetical scenario is that the difference between the relative and the Kaplan-Meier estimated survival at 19 years (63% - 21% = 42%) represents deaths from other causes (eg, cancer) than those associated with or due to AVR.”

Overall, the loss of life expectancy among SAVR patients was 1.9 years. However, the age at the time of treatment changed this estimate: patients below the age of 50 lost 4.4 years of life, for example, while those older than 80 lost only 0.4 years. There were no differences in loss of life expectancy between men and women or between patients given mechanical versus bioprosthetic valves.

Timing of SAVR Might Hinge on Age

Dovetailing with earlier studies, the current results showed that elderly SAVR patients fare especially well. “A possible explanation for this finding might be that elderly patients accepted for AVR are healthier than the average elderly individual in the general population,” the investigators note.

Durko and Kappetein agree in their editorial that the findings follow a pattern showing “SAVR can effectively ‘restore’ life expectancy in elderly patients to an almost similar level of those not having severe AS. . . . This marked loss in life expectancy [seen here] in younger SAVR patients compared with their healthy peers is thought-provoking and needs explanation.”

Differences in comorbidities as well as in the etiology and morphology of aortic stenosis across age groups might be at play, they comment.

Notably, Glaser and colleagues found that outcomes were not static during the study period—survival was higher and loss of life expectancy was lower in later years. “It is possible that patients with more comorbidities were operated with TAVR instead of surgical AVR, as TAVR was introduced during the last decade,” the researchers suggest. “However, before 2014, the majority of patients operated with TAVR were those deemed inoperable. It is also possible that pre-, peri-, and postoperative care has improved with time.”

Why do younger patients have shorter life expectancy after SAVR and what can we do to prevent it? Should we intervene earlier in patients with aortic stenosis? These important questions remain to be answered. Natalie Glaser

The results can’t be directly extrapolated to TAVR patients, Glaser stressed, but she predicted similar patterns would be seen in that population.

Moving forward, there are many knowledge gaps to fill, Glaser said. “Why do younger patients have shorter life expectancy after SAVR and what can we do to prevent it? Should we intervene earlier in patients with aortic stenosis? These important questions remain to be answered.”

The editorialists agree that focusing on the timing of intervention could potentially improve survival.

“Severe AS results in progressive and irreversible myocardial fibrosis even in asymptomatic patients, which negatively affects long-term survival after valve replacement,” they explain. “In asymptomatic severe AS, however, current clinical practice guidelines recommend valve replacement only in case of very severe AS, worsening left ventricular function, or when elevated brain natriuretic peptide levels or abnormal exercise test results are present. Some of these patients develop myocardial fibrosis, which can be detected by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Performing valve replacement before this irreversible myocardial damage occurs could improve outcomes in these asymptomatic patients.”

This idea of targeting patients for early intervention, whether by TAVR or SAVR, is being tested in the EVoLVeD trial, Durko and Kappetein point out. Another study, EARLY TAVR, is testing TAVR versus routine surveillance for patients with asymptomatic severe aortic stenosis.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Glaser N, Persson M, Jackson V, et al. Loss in life expectancy after surgical aortic valve replacement: SWEDEHEART study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:26-33.

Durko AP, Kappetein AP. Long-term survival after surgical aortic valve replacement: expectations and reality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:34-35.

Disclosures

- Glaser and Durko report no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Kappetein reports being an employee of Medtronic.

Comments