Magnetic Endoscopy Capsule Reveals GI Damage Surprises From Antiplatelets

But there were no differences in bleeding, or between clopidogrel and aspirin monotherapy, the OPT-PEACE trial showed.

Nearly all PCI patients, even those at low risk of bleeding, develop at least some gastrointestinal injury when taking dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), according to data from the OPT-PEACE randomized trial. Those who switch to a single drug after 6 months—whether that’s clopidogrel or aspirin—see less injury than those who continue on DAPT for a year, however.

The good news is that, despite the GI signals, clinically overt GI bleeding was rare with both DAPT and single antiplatelet therapy (SAPT) in the OPT-PEACE trial, which used a magnetically controlled capsule (Ankon Medical Technologies) to perform endoscopy. The device, which can be guided in increments of 2 mm with 3° changes in viewing angle, matches the accuracy of standard upper GI endoscopy and can evaluate the entire small intestine, researchers say.

“Gastrointestinal bleeding is the most-frequent major complication of antiplatelet therapy,” investigator Yi Li, MD (Shenyang Northern Hospital, China), said at a press conference this morning at TCT 2021. Yet, few details are known about its prevalence and variations, “mainly due to very limited use of standard endoscopy” in this setting, he observed.

Their study, said Li, not only provides added information about what’s occurring but also can inform future research directions on how to protect the GI health of patients taking antiplatelet drugs.

OPT-PEACE was simultaneously published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, with Yaling Han, MD (General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang), and Zhuan Liao, MD (Changhai Hospital of Navy Military Medical University, Shanghai), as lead authors.

John A. Bittl, MD (AdventHealth Ocala, FL), who co-wrote an editorial accompanying the JACC paper with gastroenterologist Loren Laine, MD (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT), praised the study’s unique design, wherein only patients shown to be free of GI damage at 6 months after DAPT were then randomized to single or dual regimens.

“It allows us, because of its systematic approach, to make some conclusions that we couldn’t really make before. The thing that was a surprise to me . . . was that clopidogrel causes about as much GI injury as low-dose aspirin. We always thought the culprit for GI injury in DAPT was low-dose aspirin, but turns out clopidogrel was just as bad,” said Bittl. He predicted prasugrel and ticagrelor would be as least as harmful as clopidogrel in this regard.

OPT-PEACE focused exclusively on low-risk patients. But for those at high bleeding risk, there’s mounting evidence—from MASTER DAPT, GLOBAL LEADERS, SMART CHOICE, STOPDAPT-2, and TWILIGHT, for instance—to support switching from dual to single antiplatelet therapy at around 1 to 6 months, Bittl commented. The current study lends support to that trajectory.

OPT-PEACE

For OPT-PEACE, investigators began by using the capsule to screen 1,028 patients 30 to 120 hours after successful PCI for stable CAD or NSTE ACS. All were low risk: exclusion criteria included age > 80 years, baseline anemia, prior gastrointestinal bleeding or ulcers within 24 months, severe chronic kidney disease, or a requirement for chronic oral anticoagulation.

Among them, the 783 without GI tract ulceration or bleeding were then enrolled and received aspirin 100 mg/day plus clopidogrel 75 mg/day for 6 months. Patients who were free from major adverse ischemic events or overt bleeding by 6 months underwent a second capsule exam.

At this point, those who still lacked GI ulceration and bleeding became the main study cohort, with a total of 505 patients randomized 1:1:1 to receive aspirin 100 mg/day plus placebo, clopidogrel 75 mg/day plus placebo, or both aspirin and clopidogrel for another 6 months. Finally, at 6 months after randomization—12 months after PCI—these patients underwent a third endoscopy exam.

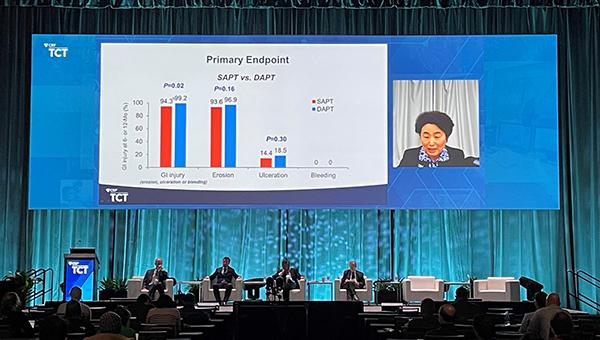

Incidence of GI mucosal injury (including erosions, ulceration, or bleeding) served as the primary endpoint. At 12 months, the rate was lower for patients who switched to SAPT at 6 months than in those who continued on DAPT (94.3% vs 99.2%; P= 0.02). Erosions, the mildest form of injury, predominated.

Bleeding was less likely to occur with SAPT compared with DAPT (5.9% vs 11.9%; P= 0.02), a difference driven by BARC type 2 bleeds (0.3% vs 2.4%; P = 0.04). There were no BARC 3-5 bleeds. The difference in BARC 1 bleeding didn’t reach statistical significance (5.6% vs 9.5%; P = 0.11). GI bleeding, in particular, was also less common with SAPT than with DAPT (0.6% vs 5.4%; P= 0.001). There were no statistically significant differences between aspirin and clopidogrel monotherapy.

Just 68 patients showed no signs of GI injury—not even erosions—at the time of randomization. For them, 6 months on SAPT also caused less GI injury by 12 months compared with continued DAPT (68.1% vs 95.2%; P= 0.006). In particular, they were less likely to develop new ulcers (8.5% vs 38.1%; P = 0.009).

“Our findings are valuable in decision-making on gastroprophylaxis and optimizing antiplatelet type and duration,” Li told the press.

But What’s the Clinical Significance?

These results “should compel cardiologists to start thinking like gastroenterologists,” Bittl and Laine assert in their editorial.

“It is known that a history of GI bleeding in a patient undergoing PCI is the strongest risk factor for bleeding after hospital discharge, which in itself is a stronger predictor of mortality than is myocardial infarction,” they write, adding, “Patients at high bleeding risk undergoing PCI should thus be considered for SAPT after 1 to 3 months of DAPT after PCI, so long as they remain at low risk of ischemic events. They should also receive proton pump inhibitors.”

They caution, though, that the “nearly ubiquitous appearance” of erosions suggests that they may not be a usual marker of GI injury. “It is possible some erosions were due to other causes or constitute a finding that is too sensitive, too nonspecific, and prone to being overread,” Bittl and Laine explain.

Bittl noted to TCTMD that it’s unlikely that serial evaluation of mild mucosal erosion would prove useful in everyday practice. “The things that really count are . . . upper GI bleeding and symptomatic ulcers. So the background high rate of mucosal [injury] is an interesting investigative finding, but of little clinical significance,” he said.

That doesn’t undermine the study’s message that single antiplatelet therapy is safer, Bittl noted. In the big scheme of things, “single antiplatelet therapy with aspirin or, say, clopidogrel probably doubles the risk of GI injury compared to using nothing at all. And then on top of that, if you go from single to dual antiplatelet therapy you increase the risk of major bleeding and GI injury by at least 60% or more. . . . .But you have to balance the risk against the likelihood of an ischemic event.”

It also points to directions for future research. Based on this study and others, said Bittl, “we now have come to believe that it’s not the direct GI toxicity of the antiplatelet agents that causes mucosal injury, but perhaps it’s their antiplatelet effect. Since ticagrelor is a more-potent antiplatelet agent than clopidogrel, it would be important [to study].”

Roxana Mehran, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), who moderated the press briefing, said that what struck her most was the lack of difference between aspirin and clopidogrel in OPT-PEACE. “I believe this wholeheartedly: that the gastrointestinal injury between Plavix and aspirin should be different. And we didn’t see that here this trial,” Mehran said, suggesting that this comparison could be underpowered.

There was a trend toward more bleeding with clopidogrel versus aspirin (8.3% vs 3.6%), though the P value was insignificant at 0.07.

Pascal Vranckx, MD, PhD (Hartcentrum Hasselt, Belgium), said, “I would’ve expected the reverse, to be honest. I would have expected more erosions with aspirin than with clopidogrel. But I must say I was blown away by the innovative structure of the design of this study. And then if you look over time, that indeed these erosions were decreasing was something I didn’t quite understand.”

Even if bleeds didn’t rise to the level of BARC, “at least this technology should pick up something” to tease out tiny disparities, Vranckx observed.

Li agreed the similarity was a surprise.

When it comes to clinical use, Li told TCTMD that the best application of magnetically-controlled capsule endoscopy would be patients at high risk—not the low-risk patients studied in OPT-PEACE. The system’s cost is around ¥3,000, or $400 US dollars, per procedure, he said.

Note: Senior study author Gregg Stone, MD, is a faculty member of the Cardiovascular Research Foundation, the publisher of TCTMD.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Han Y, Liao Z, Li Y, et al. Magnetically-controlled capsule endoscopy for assessment of antiplatelet therapy-induced gastrointestinal injury. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;Epub ahead of print.

Bittl JA, Laine L. Gastrointestinal injury caused by aspirin or clopidogrel monotherapy versus dual antiplatelet therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- The trial was supported by the China national key R&D project and an investigator-initiated grant from Ankon Medical Technologies.

- Han, Liao, Bittl, and Laine report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments