New AUC for Cardiac Imaging Follow-up in Congenital Heart Disease

The first AUC in adult congenital heart disease aims to standardize imaging follow-up in thousands of unique scenarios.

A coalition of professional societies has developed the first appropriate use criteria (AUC) for cardiac imaging in the follow-up of patients with congenital heart disease.

The new AUC, developed by the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), American Society of Echocardiography, and the International Society for Adult Congenital Heart Disease, among other groups, identifies 324 clinical indications distinguished by the type of cardiac lesion and 1,035 unique scenarios where cardiac imaging may or may not be appropriate.

“There is a paucity of guidelines in our field in terms of when to image, how often to image, and which modality to use,” Ritu Sachdeva, MBBS (Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, GA), co-chair of the writing committee, told TCTMD. “What needed to happen was for experts to come up with [a document] on the best way to follow these patients. . . As you can imagine, it’s a massive project including all of congenital heart disease.”

Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with congenital heart disease have led to increased survival and improved clinical outcomes, she noted. Many of these patients, however, need to be followed lifelong to watch for sequelae after surgery or catheter-based interventions, as well as to monitor for potential complications.

“The guidelines that we do have—for tetralogy of Fallot, transposition, or atrial septal defects—mainly focus on the technique of different [imaging] modalities that can be used and what the benefit of one [modality] over the other might be,” said Sachdeva. “Very few guidelines specify how often we need to do these studies, which is what we need in our day-to-day follow-up of these patients.”

AUC to help clinicians understand the relative risks and benefits of various cardiovascular procedures have been released by the ACC since 2005 and the first AUC for pediatric congenital heart disease was published more than 5 years ago. However, that document was geared toward initial outpatient evaluation with echocardiography, said Sachdeva. These new criteria cover all imaging modalities— transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) with and without contrast, transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), cardiac CT, stress imaging, and lung scans—for a wide range of congenital defects in both pediatric and adult patients.

The new document was published online earlier this week in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Huge Practice and Physician Variations

TTE, which is the most commonly used imaging modality, was deemed appropriate in most clinical scenarios involving the evaluation and surveillance of patients with congenital heart disease. It “may be appropriate” for routine surveillance of asymptomatic patients with a small atrial septal defect or partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection involving a single pulmonary vein, mitral valve prolapse and mild mitral regurgitation, mild aortic stenosis and/or mild aortic regurgitation, or small coronary fistula, among other scenarios.

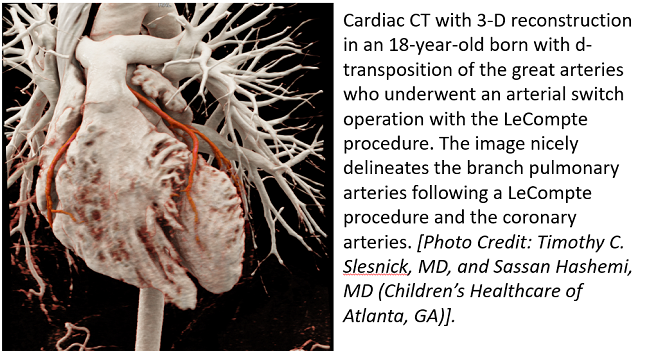

CMR and cardiac CT are more likely to be rated appropriate for more complex congenital conditions. Similarly, CT is typically considered appropriate when a definitive assessment of coronary or complex vascular anatomy is needed. Stress imaging should typically be used in the detection of coronary artery disease, an assessment of myocardium at risk, and risk stratification after coronary revascularization, according to the AUC writing committee.

In total, the use of different imaging modalities is considered appropriate in 44% of clinical scenarios, may be appropriate in 39% of scenarios, and rarely appropriate in 17% of clinical scenarios. To TCTMD, Sachdeva said there wasn’t extensive disagreement among the nine members of the AUC writing committee and the 17 physicians who served on the rating panel, although complete agreement is near impossible given the scope of the document.

“There is huge practice variation amongst different centers, and even within each center amongst different physicians,” Sachdeva said. “Some people might do an echo every 6 months for a certain of lesion, but for the same lesion somebody else might do an echo every 2 to 3 years. The question is: who’s right and who’s wrong?”

In 2018, the ACC/AHA released new guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease. At that time, the writing committee and rating panelists were in the midst of developing the AUC. As a result, the writing committee revised some clinical indications to ensure that their document matched the indications listed by the ACC/AHA, but few changes were needed.

“Interestingly, the ACC/AHA guidelines do not give us much information on the frequency of imaging,” said Sachdeva. When the ACC/AHA adult guidelines did provide direction on such timing, the AUC writing group adhered to their recommendations.

Overall, Sachdeva said she hopes the new report will be used by practicing physicians. “It’s geared toward improving care of patients in a cost-effective manner and to bring some sort of standardization to patient care in the congenital heart disease community and the way we use multimodality imaging,” she said.

The new AUC were also developed in partnership with the Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Pediatric Echocardiography.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Sachdeva R, Valente AM, Armstrong A, et al. ACC/AHA/ASE/HRS/ISACHD/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/SOPE 2019 appropriate use criteria for multimodality imaging during the follow-up care of patients with congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Sachdeva reports no conflicts of interest.

Comments