ORBITA Data Undercut the Idea PCI Does Best in Focal CAD

Stratified by iFR, PCI offered greater ischemia reduction for focal versus diffuse disease, but this didn’t translate to less angina.

When treated by PCI, focal lesions show a greater reduction in ischemia on stress echocardiography compared with diffuse disease, but this has no impact on angina relief, according to a fresh look at the ORBITA trial.

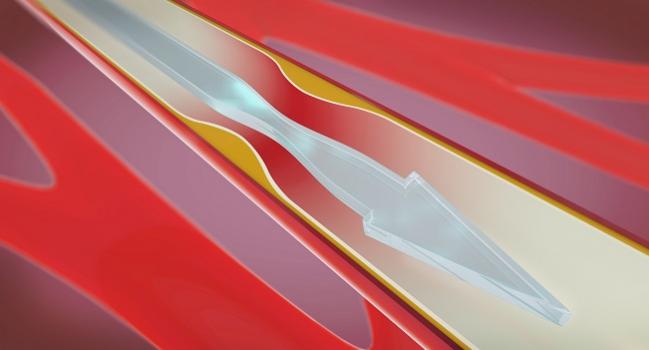

Back in 2017, the main ORBITA findings showed that PCI did not significantly improve symptoms over placebo in patients with stable CAD. Here, with the hope of teasing out whether disease patterns might influence PCI efficacy, researchers analyzed instantaneous wave-free ratio (iFR) pressure-wire pullback findings to characterize CAD as diffuse versus focal.

Christopher A. Rajkumar, MBBS (Imperial College London, England), and colleagues sought to “test the hypothesis that PCI may be more effective in treating focal stenoses than diffusely diseased arteries,” they write in their paper, which was published online in Circulation: Cardiovascular Interventions. “The theory for this assumption is clear: optimal PCI in diffuse disease is more challenging because the magnitude of physiological benefit per unit of stented segment is diminished. Furthermore, residual disease, particularly in the distal vessel, may contribute to ischemia, but will not be amenable to PCI.”

Yet the new ORBITA analysis did not bear this hypothesis out, the investigators say. Its results “once again show that the relationship between ischemia and symptoms is much more complex than we had hoped.”

Todd Villines, MD (University of Virginia, Charlottesville), who commented on the findings for TCTMD, said that, generally speaking, PCI is thought to address focal stenoses. “In reality, much of the coronary artery disease that we see is often diffuse in nature,” he explained, such that operators may treat the worst stenosis while leaving other disease behind. “It’s unclear whether there’s a difference in outcomes amongst patients with more diffuse versus focal lesions.”

This idea, explored in the current analysis, “was not the purpose of the ORBITA trial,” he cautioned, “so at best I would view the results of this [paper] as hypothesis-generating, if anything at all.”

Stratified by iFR

In the ORBITA trial, 164 out of 200 patients underwent blinded iFR pullback prior to randomization. Any iFR drop of ≥ 0.03 within 15 mm was considered to be focal disease. Among 85 patients assigned to PCI with physiological assessment, CAD was focal for 56% and diffuse for 44%. For the 79 patients assigned to placebo, the percentages were reversed, at 43% and 57%, respectively.

PCI, on the whole, was linked to greater improvement in stress echo ischemia compared to placebo (OR 3.44; 95% CI 1.83-6.47). Separating the cohort by disease pattern, researchers found that focal stenoses tended to have lower iFR values compared with diffuse CAD (mean 0.65 vs 0.88), as well as lower fractional flow reserve values (mean 0.60 vs 0.78). Accounting for these differences, PCI continued to offer ischemia reduction.

PCI improved the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) angina frequency score compared with placebo among the iFR-evaluated patients (OR 1.88; 95% CI 1.05-3.37), though there was no significant interaction with focal versus diffuse disease pattern. Freedom from angina, too, was more common with PCI than with placebo (OR 2.90; 95% CI 1.42-5.92), though again CAD pattern didn’t matter.

This is in contrast to earlier publications from ORBITA, which merely showed trends in angina improvement, the researchers acknowledge, suggesting that the inconsistency “reflects chance differences in the cohorts eligible for the analyses.”

This just reminds us that we have to try to shift how we define coronary artery disease severity. We have to . . . start thinking in terms of overall plaque burden. Todd Villines

Rajkumar et al conclude that “stratifying patients according to the pattern of coronary artery disease (focal versus diffuse) does not seem to be an effective means of predicting placebo-controlled symptomatic benefit from percutaneous coronary intervention.”

Why is this the case? The study authors offer a few ideas.

“While high-precision invasive physiological measurements made upstream in the cascade are vessel-specific and provide an invaluable measurement of ischemia in the catheterization laboratory, they may be too sensitive to make predictions of symptomatic benefit from PCI,” they observe. “However, if we accept that ischemia is a continuum and move away from dichotomous cut points, tools such as iFR pullback have a valuable place in the management of stable CAD. By preventing the loss of information content that occurs through dichotomization, these tools present a more complete assessment of vessel characteristics.”

The DEFINE-PCI trial has shown iFR can help to optimize the hemodynamic results of revascularization, the researchers note. Next up, the ongoing DEFINE-GPS trial will address whether iFR guidance can prevent MACE.

Rethinking CAD Severity

What the new ORBITA analysis does do is make the case that future trials of revascularization should “go beyond defining coronary disease by just doing two-dimensional angiography,” Villines said. Intravascular imaging with CT can be used to quantify plaque volume within segments, vessels, and the whole heart, he noted, to capture the extent of diffuse disease.

“Overall, this just reminds us that we have to try to shift how we define coronary artery disease severity. We have to stop talking about percent stenosis and start thinking in terms of overall plaque burden,” he said. “Unfortunately this study can’t help us there, because they’ didn’t assess [the latter].”

Daniell Edward Raharjo, MRes, and Vijay Kunadian, MD (Newcastle University, England), agree that disease patterns in chronic coronary syndrome (CCS) do make sense as a “possible means of further stratifying patients,” though data haven’t yet confirmed the concept.

In an accompanying editorial, they urge physicians to be circumspect. “Despite the interesting findings of this ORBITA subanalysis, which provide the first placebo-controlled evidence of lesion-pattern effects on CCS PCI efficacy, any clinician attempting to apply its results to practice should be wary due to limitations of the study,” Raharjo and Kunadian say. With only 82% of the overall ORBITA population, this substudy is underpowered, for instance, and the findings only reflect the mostly male patients with single-vessel disease enrolled by the trial, which had a “relatively short” 6-week follow-up duration.

Moreover, functional assessment in this study did not actually guide decision-making, such that diffuse disease perhaps wasn’t optimally treated, they point out. “As the PCI operators were blinded to the results of iFR pullback, they only relied on anatomic measurements of lesion length which may result in underappreciation of the extent of functionally diffuse lesions compared with physiological assessments. This would then result in the deployment of shorter stents in functionally diffuse disease, reflected by similar stent lengths between focal and diffuse lesions which were categorized using physiological data.”

These caveats mean that further research is required in a larger, more diverse population, the editorialists advise.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Rajkumar C, Shun-Shin M, Seligman H, et al. Placebo-controlled efficacy of percutaneous coronary intervention for focal and diffuse patterns of stable coronary artery disease. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e009891.

Raharjo DE, Kunadian V. Is there a difference in efficacy of percutaneous coronary intervention for focal and diffuse stable coronary artery disease? Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2021;14:e011013.

Disclosures

- Rajkumar, Raharjo, Kunadian, and Villines report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments