Real-world Stroke With TAVR: TVT Registry Insights Rekindle Cerebral Protection Debate

A 6-year registry snapshot hints that TAVR stroke rates have been stable, spurring questions for low-risk patients and brain debris.

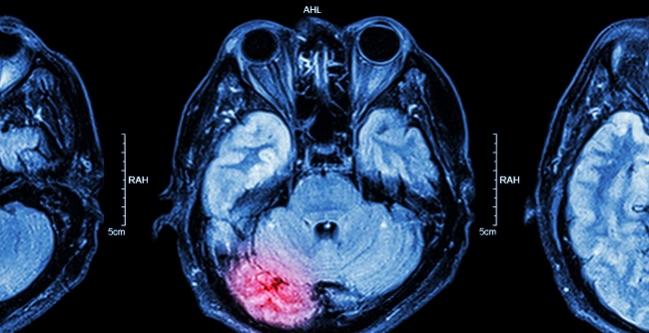

CHICAGO, IL—While stroke rates among TAVR-treated patients in clinical trials have gone down considerably over successive studies, the same decline was not seen among real-world patients at high or intermediate risk for aortic valve replacement surgery who underwent TAVR in the United States, according to 6 years’ worth of data from the STS/ACC TVT Registry. The findings have implications for the long-running discussion over the need for cerebral protection during these procedures, experts said here at TVT 2019.

And while stroke rates in the recent low-risk TAVR trials were substantially lower than those seen in the higher-risk trials, the impact of stroke is likely to be far greater as TAVR moves into younger patients, raising a whole host of new questions regarding cost, efficacy, and hard endpoint data in the cerebral protection debate.

Samir Kapadia, MD (Cleveland Clinic, OH), opened a Thursday morning session here showing an analysis of 101,430 patients enrolled in the TVT Registry who underwent TAVR at one of 521 US sites between November 2011 and July 2017.

In all cases, he said, strokes were diagnosed by the treating cardiologist. They were also confirmed by neuroimaging in 98.7% of cases and/or with neurologist or neurosurgeon confirmation in 93.8%.

For the entire time period, the rate of “any” stroke was 2.3% and the vast majority of these (2.1%) were ischemic strokes. But of note, this stroke risk remained relatively constant over the 6-year period, ranging from 2.36% in 2012, to 2.44% in 2014, to 2.27% in 2017 (P for trend = 0.217). A similar pattern was seen for ischemic stroke.

“If you look from 2012 to 2017, there is absolutely no change in the risk of stroke,” Kapadia said. “This is an important contradiction from what we saw in the randomized trials, [where] the risk is decreasing. And I think what it points to is that the patients, if they are low-risk patients [then] the risk of stroke is going to be less, but it is not the procedure that is changing that much, in itself, [and] reducing the stroke, because if you look at this, the stroke rate remains constant at about 2.2%.”

This is not trivial information to keep in mind. The strokes are not that benign. Samir Kapadia

Moreover, the implications of having a stroke were substantial, Kapadia noted. Only 36% of the TVT Registry patients who had a stroke were discharged home, as compared with 79% of patients with no stroke. More than half of patients who had a stroke required extended care or rehabilitation, and one in 10 were discharged to a nursing home. Fully 12.7% of patients who had a stroke died in the hospital and 16.7% died within 30 days; those numbers for TAVR patients who were stroke-free, for comparison, were just 2.8% and 3.7%, respectively.

Risk of stroke was lowest for transfemoral procedures (2.1%) and slightly higher for transapical/transaortic procedures (2.9%). It was highest for all “other” delivery methods, including transcarotid and transcaval (4.1%), although the number of these procedures was very low—roughly 3% of all TAVRs during this period. Risk factors for stroke were relatively similar across the different delivery methods, however, with the most common being renal impairment, prior TIA/stroke, vascular disease, and in-hospital atrial fibrillation.

“This is a very fatal disease,” Kapadia concluded. “This is not trivial information to keep in mind. The strokes are not that benign.”

The study, Kapadia noted, was led by Chetan P. Huded, MD (Cleveland Clinic), and will be published soon in JAMA.

What About Low-risk Patients?

The next question is whether any kind of difference might be seen trials and real-world results for patients with severe aortic stenosis who are at low risk for surgery. To address at least part of this question, Steven J. Yakubov, MD (OhioHealth Research Institute, Columbus, OH), pulled the 1-year stroke data from the Evolut TAVR Low-Risk Trial, the PARTNER 3 trial, and the nonrandomized LRT trial (which did not have mandated neurological assessment).

For both randomized trials, Yakubov noted, the disabling stroke risk was consistently higher at 1 year among surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR)-treated patients than among TAVR-treated patients: 2.3% versus 0.7% (log-rank P = 0.024) in the Evolut TAVR study. In PARTNER 3, Yakubov showed the rates for all stroke at 1 year (3.1% for SAVR vs 1.2% for TAVR; P = 0.04) and for death and disabling stroke at 1 year (2.9% vs 1.0%; P = 0.03). In the LRT trial, no disabling strokes were seen in the 191 trial patients alive and followed up to 1 year.

Given these low stroke rates, the big remaining questions, said Yakubov, are whether low-risk patients even need embolic protection, whether stroke rates can be reduced to zero, what the right anticoagulant or antiplatelet strategy might be, and whether certain higher-risk-of-stroke groups can be predicted to allow for selective use of embolic protection.

“Those are the questions we’re left with,” Yakubov concluded. “But the encouraging part is, the rate of stroke does go down as the risk of the patient falls.”

But the encouraging part is, the rate of stroke does go down as the risk of the patient falls. Steven J. Yakubov

Delving into some of the reasons for this in a separate presentation, Susheel Kodali, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY), showed some numbers missing from Yakubov’s presentation—namely, the 1-year disabling stroke rates in PARTNER 3. Only one disabling stroke occurred in a low-risk, TAVR-treated patient in PARTNER 3, as compared with four among SAVR-treated patients. “This is the first time we’ve seen such low disabling stroke rates,” he emphasized. “Really dramatically lower stroke rates.”

Kodali attributes these low rates to technological improvements, including a smaller delivery catheter that “allows for atraumatic passage around the arch,” a more “friendly” distal tip, and less aggressive or no use of balloon valvuloplasty during the procedure.

“Stroke is no longer the Achilles’ heel of TAVR but rather an advantage of TAVR over surgery,” Kodali concluded.

Less Stroke, More Questions

In discussions that followed the stroke presentations, David Rizik, MD (HonorHealth Medical Center, Scottsdale, AZ), sounded a note of caution, saying he was unconvinced by the decline seen in the trials and their applicability to real-world patients.

“The trouble with comparing stroke in different trials—I think there are some shortcomings of trying to do that,” he said. “We still remain in a quandary of who to try and protect and who not to protect; we still don’t have that answer. And I think there is a lot of work to be done to see who needs embolization protection and who doesn’t.”

Only one TAVR cerebral protection device, the Sentinel (Boston Scientific), currently holds US Food and Drug Administration approval, and hopes had been pinned on a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services decision last fall to create a new add-on payment that would at least partially reimburse centers for using the devices. The maximum added payment is $1,400; the device cost is $3,000, experts said here today.

But protection is still not widely used, and while there are a host of other devices in development and in testing, or even CE Mark-approved in Europe, cost remains the number one barrier to their use, as many panelists noted during the TVT session. Moreover, cost-efficacy and number needed to treat will become an even bigger question in low-risk patients, particularly if real-world stroke rates in low-risk patients are anywhere close to those seen in the pivotal trials.

“Let’s say the rates are going down,” hypothesized session co-moderator Alexandra Lansky, MD (Yale University, New Haven, CT). “I think we’re pretty convinced that that’s the case in TAVI compared to SAVR. But in the younger patient population, stroke is low frequency but high impact, so the consequences of stroke are going to be much worse. So, to the question of who to protect and not to protect, how do we balance that issue?”

In the younger patient population, stroke is low frequency but high impact, so the consequences of stroke are going to be much worse. So, to the question of who to protect and not to protect, how do we balance that issue? Alexandra Lansky

Several other members of the panel raised the issue of stroke discernment, noting that the various TAVR clinical trials measured stroke in different ways, that serial MRIs are not feasible, particularly in an elderly population, and that there is still a big question mark over the significance of smaller “ischemic hits,” the impact of which may not be known for years.

“I believe we are missing a lot of minor strokes that escape recognition by a cardiologist but that a neurologist might have recognized,” co-moderator Axel Linke, MD (Heart Center, Dresden, Germany), suggested. “We go crazy about a troponin rise after stenting and we know that this has a major impact on the prognosis of the patient, but we don’t care so much about minor neurological deficits and I think this has to change, especially when we are starting to treat younger patients that have a longer lifespan to live.”

And stroke is not the only consideration, stressed Jochen Wöhrle, MD (Ulm University, Germany). “I’m pretty sure that we in the future have to look not only at stroke but also at other symptoms like cachexia and depression,” he said, particularly in younger patients. “This is also something we might not be aware of, if you only look at the disabling stroke rates.”

Jeffrey Moses, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center), made the point that the reduction in stroke rates that has accompanied the progression to increasingly lower-risk patients could have been predicted by the fact that the low-risk trials enrolled “incredibly low” numbers of patients with the conditions now known to increase stroke rates, particular renal disease, “hostile” aortic arch, and prior strokes.

“The problem is, we don’t have a risk-prediction tool,” he said. And while such tools are in the works, they still don’t answer the question of how to make a decision on embolic protection, since some strokes are clearly occurring in patients who don’t have these predictors.

Cerebral Protection, Yes or No?

The reality, for now, is that only certain centers are using cerebral protection and very few are using it as a default strategy.

Nicolas M. Van Mieghem, MD (Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands), for one, gave an impassioned plea for cerebral protection in everyone: “Embolic protection devices are used in 80% of my cases. Why? Because the mechanistic concept is valid and sound, it is relatively easy to use with limited extra radiation and no contrast. It is safe, and it will catch debris in all of your patients. The debris size is unpredictable, there is clinical benefit, so I would strive for complete protection.”

Elaborating to TCTMD in an interview, Van Mieghem repeated an argument he’d made during the panel discussion, that in his mind using cerebral protection in everyone is a “moral issue.”

“Nowadays,” Van Mieghem said, “you have geographies where this is becoming a marketing tool: come to our center because we’re going to use embolic protection!” Or, he noted, physicians are choosing to use it if a patient is part of his or her “inner circle.”

“Then the physician will say, ‘I’m going to use a filter, because no matter what I don’t want you to have an effect from the debris.’” This is where this gets into a moral issue, Van Mieghem explained. “I think you want to have the best outcome care for all of your patients and not for selected patients.”

Van Mieghem’s hope is that prices will come down, and not just the price of the protection devices but of the valves themselves. “Thirty thousand dollars for a valve?” he said. “That’s more profit than probably the society can accept, at this point. There is no more room to introduce more safety mechanisms, and then you get these arguments that this is too costly, that we can’t afford it.”

The mechanistic concept is valid and sound, it is relatively easy to use with limited extra radiation and no contrast. It is safe, and it will catch debris in all of your patients. Nicolas M. Van Mieghem

To TCTMD, he acknowledged that the debates over cerebral protection aren’t going away soon, noting, “We’re destined to wait for the randomized trials, and without the randomized trial, the community will refuse to accept it. You will remain having the believers and nonbelievers and that’s not going to get resolved without a randomized trial. And that’s disappointing, from my perspective. So many physicians are involved in meta-analyses and single-center studies, and they want to publish these but then they don’t believe them if someone else is publishing them. But then, if it’s one of their family members who needs a TAVR, they’re going to use embolic protection.”

Lansky also spoke with TCTMD after the session, admitting that many of these same arguments have been swirling around cerebral protection since its infancy and did not disappear with the advent of add-on reimbursement. Meanwhile, a host of new devices are under development, some of them even offering “whole-body” protection. “So that’s interesting, but what is the added benefit and is there really a need for that?” she asked. “We’re already struggling so much with establishing a case for cerebral protection.”

Lansky and others made a point that has been made before, namely that cerebral protection for carotid procedures was approved and covered without ever having to prove hard endpoint efficacy in clinical trials. With TAVR protection devices, she said, “we’ve established the need, we’ve established proof of principal, but now we’re stuck in the next step, which is usage, dissemination, and cost. And yes, the field is moving towards having to do the pivotal trials, the stroke trials with hard endpoints, but then the next question is: do we have to do that with every device that comes out? And does that really make sense?”

As a thought experiment, Lansky proposes substituting deaths for strokes. If these accessory devices reduced deaths in single-center studies and meta-analyses, would uptake be so patchy and reimbursement restricted? She thinks not. And yet, “from the patient’s perspective, stroke is worse than death. So, if you said these devices were preventing deaths, I think there would be a very different dialogue,” Lansky said.

More trial results are pending, including from REFLECT, which is using the TriGuard (Keystone Heart) first- and second-generation devices; results for this 478-patient trial are due later this year. The US approval of the Lotus valve, manufactured by Boston Scientific, is also expected to affect usage and, as a result, impact real-world data, assuming there are some pricing incentives for using the Lotus and Sentinel in tandem.

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full BioSources

Multiple presentations. TVT 2019. June 13, 2019. Chicago, IL.

Disclosures

- Kapadia reports being the national co-PI of the SENTINEL trial.

- Kodali reports having equity/stock/options from Dura Biotech, Thubrikar Aortic Valve Inc; and receiving consultancy/honoraria/speakers bureau fees from Claret Medical, Meril Lifesciences, and Abbott Vascular.

- Lansky reports receiving grant/research support from AstraZeneca, Abiomed, Abbott Vascular, Bard, Boston Scientific, Biocardia, Biotronik, Cagent, Cardiatis, Conformal, Gore, Intact Vascular, Keystone Heart, Lifetech, Limflow, Medinol, Micell, Microport, Myocardia, Reva, Shockwave Medical, Surmodics, Trireme, Venus, and Veryan Medical.

- Link reports receiving consultancy/honoraria/ speakers’ bureau fees from Abbott Vascular, Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific, Bayer AG, AstraZeneca, Abiomed, Daiichi Sankyo/Eli Lilly, and Sanofi Aventis; having equity/stocks/options from Transverse Medical; and receiving grant support/research contracts from Edwards Lifesciences.

- Van Mieghem reports receiving grant/research support from Abbott Vascular, Medtronic, Boston Scientific, Daiichi Sankyo/Eli Lilly, and PulseCath.

- Moses reports having equity in Venus Medical.

- Wöhrle reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments