Rover’s Regurgitation: Veterinarian-Cardiologist Teamwork Could Speed Device Innovation, Training

Beloved household dogs develop many of the same structural heart diseases as people—why aren’t we fixing those to learn more about human therapy?

A Colorado veterinarian has a bold idea for interventional cardiology: test new cardiovascular devices—and train doctors to use them—in family pets.

Brian Scansen, DVM, is an associate professor of cardiology and the section head of cardiology and cardiac surgery at the Colorado State University (CSU) James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital. For more than a decade, he’s been forging ties with human cardiologists to build what he believes could be a fruitful collaboration for both specialties.

Brian Scansen performs a minimally invasive procedure at the CSU James L. Voss Veterinary Teaching Hospital. (Photo Credit: Kellen Bakovich/CSU photo)

“To me, this is win-win-win,” he told TCTMD. “For one, we can accelerate the development of devices that might be worthwhile in humans by testing them in animals that naturally have the disease, rather than trying to create some model in the laboratory that really doesn't mimic the human condition.”

For another, “we have patients”—that is, dogs—"that are suffering from left-sided congestive heart failure, that have severe chronic mitral valve regurgitation, enlarged left atrium, changes in LV systolic function, all of which is exactly the same as the course of the human disease,” he continued. “These dogs many times need some kind of intervention or they will die from their disease, and yet we don't have easy access to open heart procedures and definitive therapies.”

To me, this is win-win-win. Brian Scansen

Collaborating on device innovation by using household pets rather than laboratory animals is a no-brainer, Scansen believes. “The development of new human devices is advanced, the dogs potentially benefit by having a procedure they otherwise would not be able to have to treat their disease, and there’s learning on both sides [that can lead to the] acceleration of new therapies,” he said.

Unique Facility, Unique Opportunities

Scansen’s facility at CSU is like no other. It is the only active veterinary open-heart surgery program in North America (the United Kingdom and Japan also have single centers), led by veterinary cardiac surgeon Chris Orton, DVM, PhD, and, as of 2016, offers the world’s only veterinary fellowship program in interventional cardiology.

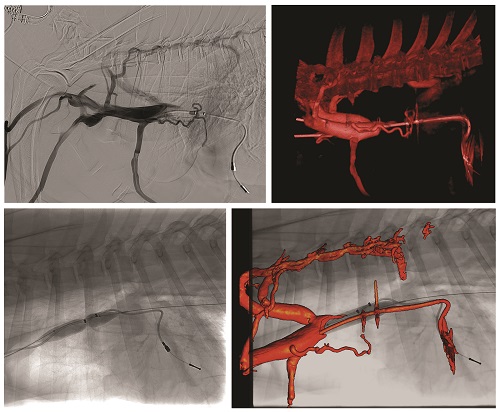

“We do all manner of image-guided procedures in the lab,” said Scansen. “Routine cases are [patent ductus arteriosus (PDA)] occlusion, balloon valvuloplasty, pacemaker implantation, liver shunt attenuation, targeted embolics (chemoembolization, intractable epistaxis), catheter-directed thrombolysis, intravascular stenting, et cetera. And it’s a hybrid OR, so we also perform the cardiopulmonary bypass and open cases in there as well.”

One of the country’s lone veterinary cardiovascular surgeons performs surgical valve repair at CSU and is leading one of the first transcatheter device trials, in dogs, using a dedicated veterinary device.

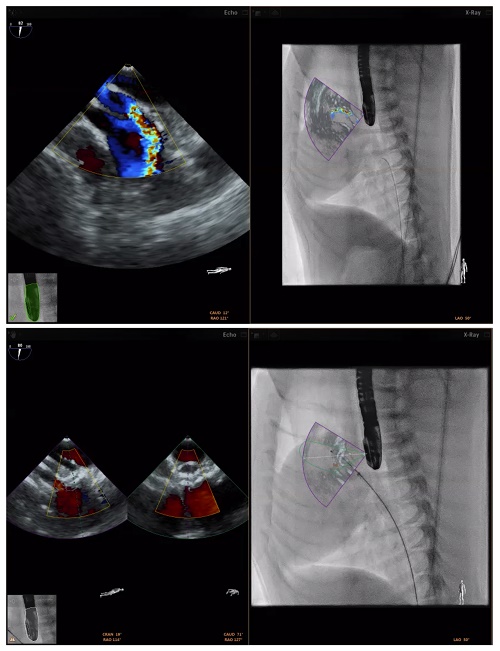

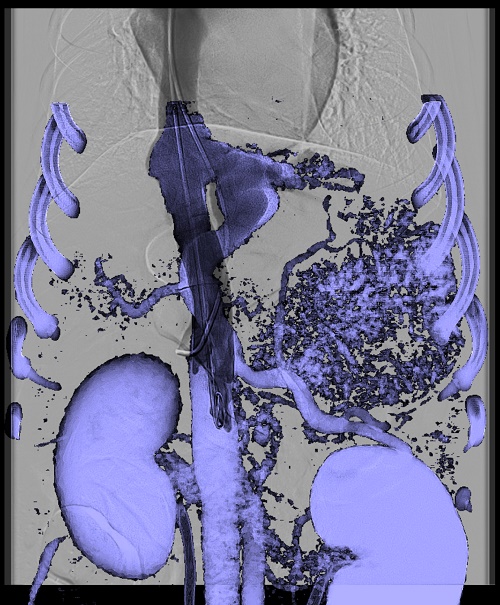

More recently, thanks to a generous donation from the family of a former patient treated at the CSU veterinary school, the cath lab was able to acquire an EchoNavigator system (Philips), which fuses live 3-D transesophageal echo with live fluoroscopy, allowing for three-dimensional device guidance.

The facility, said Scansen, also has 3-D rotational angiography as well as MR and CT fusion, which is “essentially all of the exact same equipment that would be in a state-of-the-art cath lab.” And it is continuing to evolve, he noted. While the lab already has an older CT scanner in place, an upgrade to the newest-generation CT scanner is in the works for next year.

“Our current plan for 2019 is to bring the CT side of things into this a little bit more, so actually we're in conversations with a lot of big CT imaging companies about what our needs are. It really is, I think, interesting from their perspective because we're talking about requirements of very precise spatial resolution and very fast heart rates relative to a human, so it's pushing the boundaries of what their systems can do,” Scansen explained. “But it presents an opportunity for a test bed. Can you image the heart at 180 beats per minute in a 5-kilogram patient? Because if you can do that, then the [pediatrics] world changes substantially on the human side. There's a lot of room for translation there.”

The imaging capabilities at CSU set it apart, not only from other veterinary programs but also from many of the best human hybrid cath labs around the nation. It also is far more advanced than the animal labs typically used by device companies to test their products, Scansen pointed out, making this an attractive option for companies wanting to test devices with equipment that matches the kind of labs where human procedures might take place.

Moreover, Scansen reiterated, device testing typically happens in animals that don’t even have the disease for which the device was designed (and are sacrificed when they’ve outlived their purpose). By contrast, the research subjects being proposed by Scansen are family-owned dogs. He believes owners, knowing the risks, would be eager to have their pets undergo experimental procedures that represent their only chance of survival for the very same diseases for which devices are being developed for human use.

“There are literally millions of dogs with degenerative, myxomatous mitral valve disease in the US,” Scansen pointed out. “Moreover, we're in many ways not encumbered with the same degree of regulation that the human market is encumbered by, and so what we can do is work with device companies, physicians, to develop new therapies and actually use them on dogs with naturally occurring disease.”

Who Pays?

Many of the procedures currently undertaken at CSU are paid for privately, but as Scansen highlighted, the price tag, while not insignificant, is of a different order of magnitude in dogs than in humans.

Whereas open-heart surgery in a human patient costs in the range of $150,000, the same procedure in a dog will cost $10,000 to 15,000. “So not insignificant, but not on the same scale,” Scansen said.

Moreover, the models for how procedures could be covered are multiple. In some cases, pet owners are willing to pay for a balloon valvuloplasty that will save their dog’s life, using devices repurposed from human medicine. For experimental therapies, Scansen asserted it would be both financially viable and logistically attractive for companies to partner with facilities like his and cover the cost of the experimental device, or a device used for training.

Scansen and colleagues routinely use a range of aftermarket devices developed for humans—often pediatric devices—in their canine patients. Balloon valvuloplasty for pulmonary valve stenosis, closure devices for atrial and ventricular septal defects (VSDs), and closure devices for PDA are “procedures we do fairly routinely in dogs, and much of that equipment means simply using human devices that we purchase direct from either human manufacturers or distributors that sell the veterinary market,” Scansen said.

He knows of at least one company already active in human CV device innovation that is also developing a transcatheter valve for canine patients, adding that this work is still confidential.

But this is where Scansen predicted that the field has the most to gain from collaborations between vets and human doctors. Most of the stented transcatheter valves currently on the market, even in pediatrics, are too large for most breeds of dogs, but as devices and delivery systems become smaller, the possibilities grow.

In June, Scansen and colleagues did their first bicaval stented valve implantation in a black lab named Coal who had right-sided heart failure. “That's something that's still in early-phase testing on the human side for severe tricuspid insufficiency, right-sided heart failure, ascites, et cetera,” he said. The procedure involved delivering a stented valve to the superior vena cava and the inferior vena cava.

In the first 4 months Coal did well and was starting to wean off diuretics. In the fall, he developed atrial fibrillation and some valve dysfunction, but is stable on medications, Scansen reported. Work has already begun on design changes that will help improve the next-generation valves, he added. “That's an example where there is some first-in-man of that [experience] already, but there’s not a lot of hard data on long- or even medium-term outcomes of the hemodynamics of that—do we really understand what's going on when we still leave severe tricuspid insufficiency, but put valves on either side of the right atrium? Here, there’s a dog that needed a therapy for tricuspid regurgitation, but also . . . a lot of translational value there that may inform where that type of procedure goes on the human side.”

Cardiological Collaboration

The idea of cross-species collaboration is not new. According to Scansen, the University of Pennsylvania was one of the first pioneers in uniting cardiologists and veterinarians, back in the 1950s, and other institutions have followed. Interventions for dogs with cardiovascular disease have been done since the 1980s, he added, and “grew dramatically” after 2000.

Around 2005, Scansen began working with pediatric cardiologist John Cheatham, MD, director of cardiac catheterization and interventional therapy at the Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, OH. Their early alliance led to some of the first congenital heart disease interventions in dogs, including pulmonary valve stenting and hybrid periventricular VSD closure.

While Scansen has since moved on to CSU and Cheatham is semiretired, another pediatric interventional cardiologist, Darren Berman, MD, co-director of cardiac catheterization and interventional therapy at Nationwide Children’s, has taken up the mantle. Berman now works with veterinary cardiologist Karsten Schober, DVM, PhD, who is the cardiology and interventional medicine section head at Ohio State University, and the two have rebuilt the connection between their two specialties first forged by Scansen and Cheatham.

Speaking with TCTMD, Berman recalls Schober coming to one of their heart team meetings to present a case of a dog with significant venous blood-vessel narrowing, and together the group brainstormed a solution that ended up with the dog receiving a stent.

Berman predicts that only good things can come out of this type of partnership. “We don’t know where medicine and science will be 20 to 30 years from now, and what we’re doing now is different from what we were doing 20 and 30 years ago. These kind of collaborations, working together, oftentimes can spark new ideas that the individual, working on his own, wouldn’t have thought of,” Berman said. “That can have a big impact on society. It happens all the time in academic medicine where two people meet to discuss something and something new comes out of it. That’s usually two different specialists, taking care of humans, but I think this is a realistic and fair comparison. You could take something from the veterinary world and something from the human world, and the two could turn into something you just wouldn’t know otherwise about.”

You could take something from the veterinary world and something from the human world, and the two could turn into something you just wouldn’t know otherwise about. Darren Berman

Since forging this new connection, the two specialists have spent time observing each other’s work and discussing therapeutic strategies. “It comes down to growth and learning within your own field,” Berman said. “Karsten spent time observing cases over here in the cath lab that I was doing, so he has been able to learn and grow and improve his technique and practice. As for me, I may see a new way that he does something to help an animal and think: wait a minute. That’s not something that gets taught routinely in the human world but has some application. That sort of crosstalk that happens all the time in academic medicine allows for a more rounded development of one’s own career.”

Cutting-Edge Interventions

As the facility at CSU started coming into its own, Scansen put out a call to interventional cardiologists who might be interested in collaborating on some of the newest advances in the field. He wanted to observe certain procedures and was looking for human cardiologists who might be interested in scrubbing in with him.

John Carroll, MD, was one of the physicians who took the bait. Director of interventional cardiology at the University of Colorado, Denver, Carroll has long had an interest in structural heart interventions. Around the time he first heard about Scansen, his daughter was an undergrad studying animal sciences at CSU. When his daughter’s chihuahua, Mango, developed shortness of breath she took him to her local vet, who referred them to a veterinary cardiologist in Littleton, CO.

“I watched him perform an echo, and lo and behold, Mango had severe [mitral regurgitation (MR)] with prolapse of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve,” Carroll recalls. “Mango was about 10 years old, and MR does increase as dogs age. So we put Mango on medical therapy, which was quite similar to human medicine (vasodilator therapy and diuretics), and Mango did okay for about a year and then died from refractory heart failure. Of course, the whole time, my daughter was saying, ‘Dad, can’t you just do a MitraClip?’”

Of course, that whole time, my daughter was saying, ‘Dad, can’t you just do a MitraClip?’ John Carroll

The MitraClip (Abbott) system, of course, would have been too large for Mango, but Scansen said that the push towards miniaturization is another key reason why device companies should take his proposal seriously. Other devices, still investigational in the US, might already be suitable for canine patients. The Harpoon device (Edwards Lifesciences), Carroll pointed out, “would be perfect for a small dog.”

“Mango had this anterior leaflet that was going back into his left atrium, and putting in a new chord and tethering that back to its normal location I thought would have been a wonderful experiment for the development of this technology,” Carroll said. “Secondly, this does roll over into training, where one of the major hurdles we all face in these innovative new valve treatments is the learning curve, which is substantial. And gee, if you have an animal model, with the same disease, you have a win-win: you're getting trained and the animal is being benefited.

“So I don't know where this will go, but [this] might be very important in bringing this issue of collaboration with the veterinary community to the forefront and maybe device companies haven't realized this,” Carroll suggested.

TCTMD contacted a handful of device companies, asking whether they would consider partnering with vets like Scansen to either develop new devices or to train human cardiologists on canine patients. All of the companies contacted declined to comment or directed TCTMD to their published policies on animal research.

But Scansen hopes the tide can turn, particularly as companies and physicians realize what can be done in a state-of-the-art facility like CSU’s. The Philips fusion imaging system that the hybrid lab acquired this year is not widely in use in human hospitals, and in many ways the work Scansen is doing could help validate the use of this imaging modality. Over the past few years, Carroll has visited Scansen’s lab to watch some of the interventions he’s doing in dogs, while Scansen has also been an observer in Carroll’s cath lab at the University of Colorado.

For decades or centuries, animals have been used for research to try and develop human products, and now we have the ability to bring that circle back around. Brian Scansen

Scansen told TCTMD that his proposal typically gets one of two responses. “You either get the 'I'm busy with what I'm doing and that's nice: go and play with the puppies,’ and I understand that. I respect that. But then you also get the other group, people like Dr. Carroll, who is at a point in his career where he sees the novelty in it [and] he also sees the value not only to animals but also to translation” to human medicine.

Though clearly proud of what he’s done for his patients and eager to do more, Scansen is sensitive to this work being misconstrued.

“I think it's probably important to state something which I think is fairly obvious but is worth saying: there's no question human medicine and the life of a human is in a different realm than veterinary medicine and the life of a dog,” he stressed. “Veterinary medicine is clearly a luxury item. So yes, to some extent, we are offering a service to people whose pets more and more, particularly for millennials and people who didn't have children, [have] become more and more a part of the family.”

But Carroll, for one, thinks more (human) cardiologists would enjoy the novelty of this kind of teamwork and thinks companies, too, could benefit. “I can't wait until TCT 2020! Maybe the meeting will come back to Denver and we could do a live case, a mitral intervention, and we won't tell anyone until the end of the case, when we'll pull down the cover and there will be Fido," he joked.

There’s one more reason to find a way for human medicine and veterinary medicine to move more closely together, Scansen suggested.

“To me it completes a circle. For decades or centuries, animals have been used for research to try and develop human products, and now we have the ability to bring that circle back around. This may not appeal to many citizens, but it does appeal to me,” he commented. “It’s animals that brought most of these devices to market that work in humans. Why can't we bring them back to animals and treat animals with the same diseases?”

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full Bio

Comments