Similar Mortality, Higher Early Stroke Risks in TAVR for Bicuspid Aortic Stenosis

The registry data hint that TAVR may be possible in this setting, but experts warn that not all bicuspid valves are the same.

Patients with bicuspid and tricuspid aortic stenosis at high or intermediate risk for surgery undergoing TAVR with the latest-generation Sapien 3 (Edwards Lifesciences) valve have similar rates of all-cause mortality at 30 days and 1 year, according to a new analysis of the STS/ACC TVT Registry.

The risk of stroke at 30 days, however, was significantly higher among patients with bicuspid valve anatomy compared with patients with tricuspid aortic valves, but the study showed there was no difference in stroke rates at 1 year. Additionally, there was no difference in valve hemodynamics nor any difference in the risk of moderate or severe paravalvular leak between TAVR-treated patients with bicuspid versus tricuspid anatomy.

“The data are a good start,” lead investigator Raj Makkar, MD (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA), told TCTMD. “We showed at least that the key things, especially survival, were not very different. Also, in terms of hemodynamics, which was another big concern, these valves seem to be functioning with similar reduction in gradients and similar valve areas. The paravalvular leak rates are very similar. At 1 year, they’re not very different. This gives us more ammunition to be a little more aggressive and to start to actually talk about using TAVR in bicuspid aortic valves.”

Makkar cautioned against overexuberance, however. These new results, along with findings from the low-risk randomized trials, should not be used to automatically assume TAVR is equivalent or better than surgery in bicuspid aortic stenosis. “This is valuable information because it helps us get started,” he said. “At the same time, we must be careful not to misuse the information to treat a 60-year-old with bicuspid [aortic stenosis]. All bicuspids are not the same. Bicuspid aortic stenosis is a heterogenous cohort with different types of anatomy.”

Like Makkar, Mohamed Abdel-Wahab, MD (Heart Center Leipzig, Germany), who was not involved in the study, stressed these early registry results should not be taken as a green light for operators to routinely implant transcatheter heart valves in patients with bicuspid aortic stenosis.

“I would be concerned about giving the message that treating bicuspid valves is the same as treating tricuspid valves, saying, ‘Let’s expand and invite everybody to do this,’” Abdel-Wahab told TCTMD. “It’s a different animal and requires different experience.” Proper valve sizing, device selection, and patient selection are all more challenging in the setting of bicuspid aortic valve stenosis, he said. “I’d be concerned about opening this door and then after a couple of years start seeing problems that could have been prevented.”

It’s a different animal and requires different experience. Mohamed Abdel-Wahab

In an editorial accompanying the study, Colin Barker, MD (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), and Michael Reardon, MD (Houston Methodist Hospital, TX), also draw attention to the two most recent randomized controlled trials in low-risk patients, noting that these studies provide a compelling argument for TAVR becoming the preferred treatment strategy in this younger patient population. Although the US Food and Drug Administration hasn’t yet expanded the indication to low-risk patients, that approval is expected, as are changes to clinical guidelines recommending TAVR in the low-risk setting.

“When this occurs, the clinicians who provide care for patients with structural heart disease will need to grapple with patient age and whether TAVR is appropriate for patients who had been excluded from previous TAVR trials because of their bicuspid aortic valves,” write Barker and Reardon. “The prevalence of bicuspid aortic valves in the patient group older than age 80 years is about 20% but is approximately 60% among younger patients aged 60 through 80 years and will represent a greater percentage of the patients who are evaluated for severe aortic stenosis.”

Roughly 3% of TAVRs Done in Bicuspid Valves

In this registry-based prospective cohort study published June 11, 2019, in JAMA, approximately 3% of patients undergoing TAVR at 552 US centers had a bicuspid aortic valve. From 81,822 patients with severe aortic stenosis treated with TAVR, including 2,726 with bicuspid aortic valves and 79,096 with tricuspid valves, they used 25 baseline patient characteristics to conduct a propensity-matched analysis of 2,691 matched pairs with bicuspid and tricuspid aortic stenosis, respectively.

At 30 days, mortality rates were similar in patients with bicuspid and tricuspid anatomy (2.6% vs 2.5%; P = 0.82), while the risk of stroke was higher among those with bicuspid aortic stenosis (2.5% vs 1.6%; P = 0.02). At 1 year, mortality and stroke risks were similar between the patient groups. The need for a new permanent pacemaker at 30 days was higher among those with bicuspid aortic stenosis (9.1% vs 7.5%; P = 0.03), and while the risk of procedural complications requiring conversion to open-heart surgery was low in both groups, these complications occurred more frequently in patients with bicuspid valves (0.9%) than those with tricuspid anatomy (0.4%; P = 0.03).

Functional status and quality of life improved in both patient groups, and there were no between-group differences for those with bicuspid and tricuspid anatomies.

Regarding the stroke rate, Makkar said bicuspid valves tend to be more calcified than tricuspid aortic valves, and that operators often perform more frequent balloon dilatation before and after the procedure, which might explain the higher risk of stroke at 30 days. He pointed out that most of these cases were performed without the use of cerebral embolic protection so there are ways to lower the early stroke rate.

Abdel-Wahab also was cautious interpreting the stroke data at 30 days given the limitations of registry data, particularly since it’s not entirely clear how bicuspid valve anatomy was identified or confirmed, but he said the finding makes sense given the increased calcification and the greater use of balloon dilation.

Not All Bicuspid Valves Are the Same

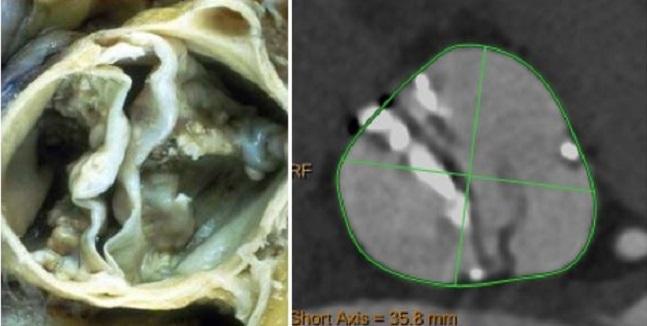

With bicuspid aortic valves, there is more wear and tear on the valve and patients present earlier with aortic stenosis or regurgitation. Although there are technical challenges with TAVR in these individuals, Abdel-Wahab emphasized that not all bicuspid valves are the same.

“There are different phenotypes, and while this probably doesn’t make a difference to a surgeon when he’s treating a diseased bicuspid valve because the leaflets are going to be excised anyway, when you’re doing TAVR the different phenotypes contribute to different technical challenges,” he said. “We’re starting to understand this with the use of more sophisticated imaging, such as CT. We’re diagnosing more bicuspid valves than we did in the past when we solely depended on echocardiography and we’re started to really differentiate the phenotypes.”

The Sievers and Schmidtke classification is most commonly used to categorize valve anatomy, with the valves classified based on the number of raphes, or fused leaflets (0, 1, or 2), according to editorialists Barker and Reardon.

In experienced, high-volume centers, the differentiation of bicuspid valve anatomy is starting to influence decision-making when it comes to treatment strategies. Depending on the anatomy, some patients might be better candidates for TAVR than others or for a particular type of transcatheter heart valve, said Abdel-Wahab. “We don’t have a lot of data to guide us in this context,” he said. “There are data that are coming, but experience tells us you can’t put all bicuspid valves in one basket.”

This is valuable information because it helps us get started. Raj Makkar

For a low-risk patient who is a good candidate for surgery, there is no reason to perform TAVR on their bicuspid valve if the anatomy is not favorable to the transcatheter approach, he added. Makkar agreed, noting that it will be crucial to identify bicuspid patients who respond to TAVR given their risk profile and eligibility for surgery.

And while a randomized controlled trial of TAVR versus surgery in patients with bicuspid aortic stenosis might appear straightforward, Abdel-Wahab said it would be unfair to lump all patients together at this point given the anatomical heterogeneity of bicuspid valves.

“We still don’t know whether TAVR functions equally well in all these phenotypes, both in the short term and more importantly in the long term,” he said. “There might be some phenotypes where the hemodynamics are suboptimal even if you obtain a good result initially. This could influence the long-term durability of the device. All of these aspects we don’t understand yet. Moving now to a randomized trial would be unfair to TAVR technology before we understand which patients could be equally treated with both methods.”

Photo Credit: Kornowski R. Bicuspid Aortic Stenosis: How To Treat. Presented at TCT 2018. September 23, 2018. San Diego, CA.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Makkar RR, Hoon S-H, Leon MB, et al. Association between transcatheter aortic valve replacement for bicuspid vs tricuspid aortic stenosis and mortality or stroke. JAMA. 2019;321:2193-2202.

Barker CM, Reardon MJ. Bicuspid aortic valve stenosis: is there a role for TAVR. JAMA. 2019;321:2170-2171.

Disclosures

- Makkar reports grant support and consulting/speaking fees from Edwards Lifesciences, Abbott, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific.

- Reardon reports financial support from Medtronic.

- Abdel-Wahab reports receiving honoraria/consulting fees from Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic.

Comments