In STEMI, Giving Heparin Pre-Cath Lab May Boost Reperfusion: HELP-PCI

Logistical challenges may impede heparin pretreatment by emergency personnel and complicate communications.

WASHINGTON, DC—For STEMI patients undergoing PCI, pretreatment with a loading dose of unfractionated heparin at first medical contact improves spontaneous reperfusion of the infarct-related artery without an increase in major bleeding, according to new randomized data from China.

Early heparin administration in these patients should “be considered to reduce the inherent delay from first medical contact to the cath lab in the current regional networks, thereby attenuating myocardial injury and improving clinical prognosis in patients with STEMI,” said Jing Chen, MD (Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, China), who presented the findings today at TCT 2024.

Unfractionated heparin is typically administered at the time of primary PCI to facilitate spontaneous reperfusion and reduce clot burden, with most centers giving the drug at the time of intervention. In 2022, an analysis of the SCAAR registry suggested that heparin pretreatment in STEMI patients, either in the ambulance or emergency department instead of the cath lab, led to a reduction in coronary artery occlusion without increasing the risk for bleeding, as well as some signs of better survival.

Discussing the HELP-PCI trial following its presentation, George Dangas, MD, PhD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), called the study “a very important refresher” for physicians who may have forgotten the mechanisms and actions of this long-standing agent, or have questioned the ideal timing for its use.

“Heparin has been sort of grandfathered into our treatments of many angioplasty and related procedures, and many of the early studies lacked the detail and the size we are now accustomed to over the last few decades,” he said.

Dangas did note that the mostly male population and high rate of smoking (44%) distinguishes this population from most angioplasty patients in the US. “However, despite this very, I would say, high bar, heparin managed to show a difference,” he added.

Pretreatment Wins Out

For HELP-PCI, Chen and colleagues randomized 999 STEMI patients slated for primary PCI (mean age 60 years; 82% male) to receive 100 U/kg of unfractionated heparin at first medical contact (n = 505) or in the cath lab (n = 494). There were three patients assigned to receive heparin in the cath lab who crossed over to the early heparin arm and 11 patients who were randomized to receive heparin at first medical contact who received it in the cath lab.

The total dose of heparin given during primary PCI was higher in the pretreatment group than the cath lab group, especially for the subcutaneous dose. More than 99% of patients received full-dose aspirin and more than 89% of patients received full-dose DAPT, primarily with ticagrelor.

Unsurprisingly, symptom-onset-to-heparin time (3.1 vs 2.85 hours; P = 0.002) as well as first-medical-contact-to-heparin time (71 vs 35 minutes; P < 0.001) were longer in those randomized to receive the drug in the cath lab compared with at first medical contact. Heparin-to-wire time, however, was longer in the pretreatment group (37 vs 12 minutes; P < 0.001).

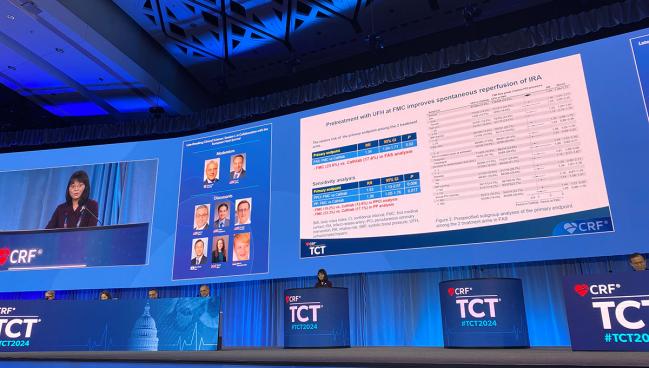

Giving heparin before patients reach the cath lab was associated with a higher likelihood of achieving TIMI flow grade 3 of the infarct related artery at diagnostic angiography before primary PCI, the study’s primary endpoint (23.6% vs 17.6%; RR 1.34; 95% CI 1.04-1.71). This finding held true in sensitivity analyses looking only at patients who received primary PCI (19.2% vs 12.6%; RR 1.53; 95% CI 1.13-2.07) as well as the per-protocol population (23.3% vs 17.1%; RR 1.36; 95% CI 1.05-1.76). The result was also consistent across a range of subgroup analyses including sex, age, body mass index, symptom time, P2Y12 inhibitor received, and operator PCI volume.

At 30 days, patients treated with heparin at first medical contact compared with in the cath lab had a significantly lower risk of MACCE (2.2% vs 4.7%; HR 0.47; 95% CI 0.24-0.91)—comprised of all-cause death, cardiac death, admission for heart failure, MI, stent thrombosis, unplanned revascularization, and stroke—and this finding was driven by more hospitalizations for heart failure in the cath lab arm (0 vs 0.4%; P = 0.023).

At 1 year, there was no longer a difference in MACCE between the cohorts (5.5% vs 6.7%; HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.50-1.35).

The 1-year data is not a surprise, said Dangas. HELP-PCI shows that heparin pretreatment makes the interventionalist’s job “easier” and it’s “very reasonable” that there was no sustained MACCE benefit at 1 year, he said. “It helps us get positive 30-day results, and the benefit, I would say, expires after that.”

The researchers found no differences in either epicardial and myocardial reperfusion after primary PCI or in major bleeding (BARC ≥ 2) at 30 days based on the heparin strategy used.

‘Logistically Challenging’

What message this study has for health systems outside China isn’t clear.

In a press conference, Celina Yong, MD (Stanford University School of Medicine, CA), offered a few caveats. Giving heparin at the ambulance stage or earlier is challenging, she noted, because it requires emergency personnel to determine whether a patient is having a STEMI and then to convey accurate information on how much and what time heparin was given, “so we can figure out how much more to give or where to take it from there,” she said. “That handoff can be logistically challenging.”

Juan Granada, MD (Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY), who moderated the press conference, observed, “This is where AI and smart communication systems and triage could potentially impact these patients.”

To TCTMD, Yong said “a lot of things have to go right in order for this to work in the US, since we have a lot more variability in our healthcare system than what Dr. Chen described in the HELP-PCI trial.” Notably, Chen said each region in China has a singular government-sponsored emergency medical services (EMS).

“Hospitals in the US often receive STEMI patients from multiple different EMS providers—these can be different private companies that employ EMS providers who may operate in slightly different ways and often don't share access to our electronic health record,” Yong explained. Asking EMS to accurately diagnose a STEMI in the field “and distinguish it from other competing diagnoses as well as evaluate the patient for potential bleeding risk [is] a lot to ask.”

One way these findings could be incorporated into US practice might be to focus on heparin administration in the emergency department, if applicable, which is something certain institutions already do, she added. “Overall, it's more feasible since at least a physician has seen the patient by that point, and we already have established communications with the ER.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Chen J. Early administration of heparin at first medical contact versus in the cathlab for STEMI patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention (HELP-PCI): a multicenter, randomized trial. Presented at: TCT 2024. October 28, 2024. Washington, DC.

Disclosures

- Chen reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments