Surgical TAVI Explants Are Risky and Rising: STS Data Carry a Warning

Worrisome signals seen in a comparison of redo procedures carry a message for interventionalists and surgeons alike.

BOSTON, MA—The number of TAVI patients who end up needing a later SAVR for a failing TAVI valve is rising faster than many cardiologists may realize. What’s more, a new analysis is warning that the risk of dying during this second procedure is starkly higher than that seen in patients whose initial valve implant was surgical, followed by a second SAVR device.

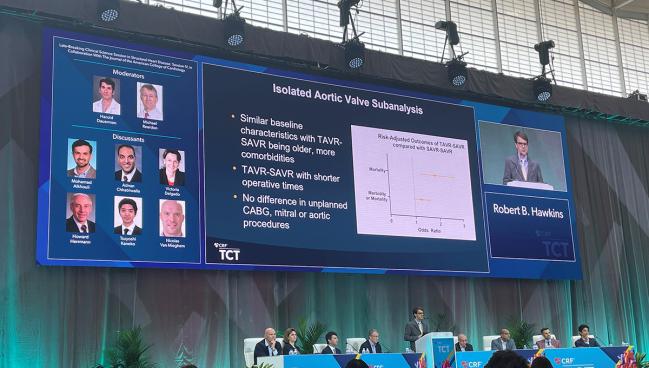

Speaking to the press ahead of his late-breaking clinical science presentation here at TCT 2022, Robert B. Hawkins, MD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), stressed that explanting a TAVI device to implant a new surgical valve is a vastly different procedure than a straightforward SAVR, or a repeat SAVR.

“It is not the same operation,” he said. “It is very different.”

Both surgeons and interventionalists need to know that a TAVI in TAVI is not going to be the solution for many patients, that the number of TAVI explants is ticking steadily higher, and that the complex procedure to remove a TAVI device to implant a surgical valve is foreign to the vast majority of surgeons.

Patients, Hawkins added, need to know this at the time of their first procedures.

SAVR After TAVI

Hawkins and colleagues delved into the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Participant User File database from 2011 to 2021 looking for all aortic valve replacement cases, excluding any nonbioprosthetic valves and any patients for whom STS risk score details were missing. Patients were then separated into groups based on their later procedures.

In all, 14,826 patients who’d undergone a first SAVR underwent a subsequent SAVR, 544 patients initially treated with TAVI underwent a subsequent SAVR, and fully 318 patients had had a SAVR, then a valve-in-valve TAVI, followed by a second SAVR.

Looking first at volumes and trends, Hawkins showed that repeat surgical valve procedures have been relatively stable over the last 5 years, while the number of both repeat TAVIs and SAVRs after TAVI have been rising steadily. By 2026, noted Hawkins, the number of surgical explants of TAVI valves is expected to reach 500 per year.

In an overall, unadjusted comparison between groups, the TAVI-SAVR patients—not surprisingly—were more likely to be older, with more comorbid disease and more prior PCI than the SAVR-SAVR patients.

But strikingly, overall rates of complications were significantly higher in the TAVI-SAVR patients, with operative mortality reaching 17%, as compared with 12% in the SAVR-TAVI-SAVR patients and 9% in the SAVR-SAVR patients (P < 0.001).

[T]his risk needs to be disclosed to patients and accounted for in plans for lifetime management of aortic stenosis. Robert B. Hawkins

Acknowledging that these groups are “not the same at baseline,” Hawkins and colleagues performed hierarchical regression modelling using STS risk score. Here, TAVI-SAVR patients faced a 1.5-fold higher risk of mortality than the SAVR-SAVR patients, as well as an increased risk of combined morbidity mortality.

Drilling down further to consider only patients undergoing isolated aortic valve replacement, a risk-adjusted analysis indicated that the odds ratio for mortality in the TAVI-SAVR patients as compared to SAVR-SAVR rose to 1.7. Following additional propensity-score matching looking only at the isolated aortic valve replacement patients, the TAVI-SAVR patients had higher operative mortality than the SAVR-SAVR patients (11.3% vs 6.7%), higher failure to rescue (32% vs 16%), higher rates of renal failure, and longer ICU stays.

“TAVR explant remains a low-volume, but increasing operation with increased risk when compared with repeat SAVR,” Hawkins concluded. “Consideration must be given to centralizing these cases at high-volume centers of excellence and needs further study.”

Moreover, he urged, “this risk needs to be disclosed to patients and accounted for in plans for lifetime management of aortic stenosis. For those patients who are likely to outlive their first valve replacement and are not TAVR-in-TAVR candidates, then a surgery-first approach should be strongly considered.”

Surgeons, too, need to shoulder some of the responsibility, he continued. “As surgeons, we also then have to design our operations for future valve and valve, with aggressive use of root enlargement and internally mounted tissue valves should be considered.”

Not Preaching to the Choir

Speaking with TCTMD, study co-author Shinichi Fukuhara, MD (University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI), said that they had been very intentional in submitting this data to the TCT 2022 meeting, rather than a surgical meeting, because they want interventionalists to be aware of the number of cases in which a TAVI-in-TAVI is simply not an option. Fukuhara estimated that the number of people ineligible for a repeat TAVI may be somewhere in the realm of 50% of patients. Hawkins called it “an area in dire need of more research,” adding: “We just don’t have a good way of knowing at this time who will or will not be candidates, but there is a significant number for sure who will not be candidates for TAVR-in-TAVR.”

For now, surgical explant of a TAVI valve is a complicated and risky procedure that many surgeons are unfamiliar with.

Indeed, during the formal discussion following Hawkins’ late-breaking presentation, moderator Michael Reardon, MD (Houston Methodist, TX), noted that these investigators are US leaders in this procedure, joking that Fukuhara was on a mission “to take out every TAVR valve in the state of Michigan.”

“You guys have done a lot now,” Reardon continued, “but on average, across the country, the mean number of TAVR removals by surgeons is one, and they're often done by surgeons that have never really implanted a TAVR valve or seen a TAVR valve.”

Hawkins, in response, noted that a low-volume of explant procedures leading to an uptick in operative mortality and “failure-to-rescue” is only part of the problem. “A lot of these patients with failed TAVR valves are also not undergoing surgery,” he said. “They are palliative. And so really what we're looking at is the fringes of these failed TAVRs and what's happening to them.”

Suzanne V. Arnold, MD (Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute/University of Missouri-Kansas City), speaking during the press conference, noted that patients who were getting transcatheter valves between 2011 and 2015 were very different than many of the patients undergoing TAVI today—transcatheter devices were only US Food and Drug Administration-approved for the highest-risk patients and many had already been deemed too high risk for surgery at the time of their TAVIs.

“I worry about the ability to account for all of those differences between those patients that were felt to only be allowed to have TAVR during that time period with just an STS risk score, because there's so much more, to patient characteristics, patient risk than an STS risk score,” she said.

Speaking to this point with TCTMD, Hawkins and Fukuhara suggested that the wealth of data collected in the STS score is richer than many interventionalists may realize, and their findings should not be discounted just because they’re not randomized—at least 60 different factors were used to match patients, Fukuhara noted.

That said, Hawkins added, the picture is only going to get more complicated as more and more low-risk patients undergo TAVI procedures. “As we get into the lower risk categories, palliative is no longer really an option, so I think this is going to become ever more increasing. . . and I do think that there's a learning curve.”

On the other hand, noted Tsuyoshi Kaneko, MD (Brigham And Women's Hospital, Boston, MA), one of the late-breaking discussants, the fact that many of these patients were likely high surgical risk for their first procedures would also have an impact on their later mortality risk. “As the risk comes down, can we lower that mortality? And does that come with greater experience—the operator experience, institutional experience, or the societal experience? I think that'll be the key to see,” he said.

Lessons for All

For surgeons, Hawkins suggested, “really understanding the biventricular anatomy going in is important. TTE we’ve found to consistently underestimate the posterior [paravalvular leak] and we're underestimating the load on the LV, translating to RV failure and failure to rescue. So I think this is a learning curve and most centers are going be on that learning curve for at least a decade, because of how few they do.”

For interventionalists who are perennially cheerful about being able to “innovate out of this problem,” said Hawkins, these data should give them pause.

“That’s always going to be an answer and it's very optimistic,” he said, but pointed by way of example to new valve-in-valve data presented in the same late-breaking session showing a higher risk of mortality among patients undergoing bioprosthetic valve fracture to accommodate a TAVI device. “What we see is that whether it's BASILICA or fracture, the outcomes are not as good as hyped by the people who pioneered those and are expert at those.”

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full BioSources

Hawkins RB. Increased risk of surgical aortic valve replacement after prior transcatheter versus surgical aortic valve replacement. Presented at TCT 2022. September 18, 2022. Boston, MA.

Disclosures

- Hawkins reports having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments