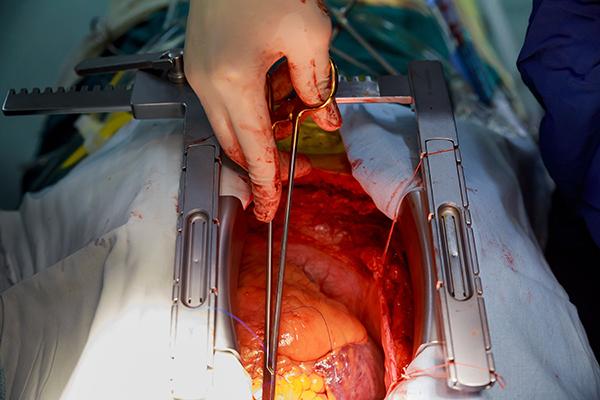

Using Donor Hearts After Circulatory Death Is Feasible for Transplantation

Promising results in organs transplanted after cardiopulmonary arrest raise hopes for expanding the limited donor pool.

Expanding the criteria to include hearts donated after circulatory death (DCD) could contribute potentially nearly 300 additional adult hearts for transplant in the United States, say researchers.

“I think studies like ours provide reassurance to transplant centers that heart transplantation from well-selected DCD donors appears to be safe and feasible,” lead investigator Shivank Madan, MD, MHA (Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY), told TCTMD, adding that further studies with longer follow-up—5 years or more—are still needed.

In the United States, heart transplantation relies on organs donated after brain death (DBD), thereby limiting the amount of hypoxia to the heart, which is continuously perfused until it is removed from the deceased donor. One strategy proposed to counter the shortage of organs is to use hearts from donors pronounced dead after the heart has irreversibly stopped beating, but ethical and technical challenges remain.

In the setting of DCD, however, the donor heart is exposed to a degree of “warm ischemic injury” that results from inadequate oxygenation after circulatory arrest or perfusion after the withdrawal of life support. Concerns about ischemic injury, including the inability to assess the extent of damage, have historically prohibited the use of DCD hearts, Madan explained.

“However, over the last few years transplant centers have developed various protocols for organ procurements from DCD donors that help to overcome this,” he said. “After declaration of death and a mandatory stand-off period, DCD donor hearts may either undergo normothermic regional perfusion [NRP] within the donors or DCD donor hearts may be perfused in ‘ex vivo organ perfusion systems.’ These new technologies allow transplant physicians to assess whether DCD donors are suitable for transplantation or not.”

Programs in the United Kingdom and Australia have successfully shown that transplantation with DCD donor hearts is feasible. The researchers say the purpose of the present study, which was published online ahead of print January 10, 2021, in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, was to investigate the current status and early post-heart transplantation outcomes with DCD organs in the US, where such heart transplantations are infrequent.

Highly Selected DCD Donors

Using the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database, the researchers identified 3,611 adults meeting the criteria for death due to irreversible cardiopulmonary arrest who donated their hearts. Of these DCD donor hearts, just 136 were used for transplantation. Hearts implanted were from patients who were significantly younger (median age 29 vs 47 years) and who were less likely to female (10.3% vs 34.6%). Additionally, the DCD hearts used in transplantation were more likely to be from patients with type O blood and who had a lower body mass index, a higher left ventricular ejection fraction, less hypertension, and less diabetes than the DCD donors where the hearts were not transplanted (P < 0.001 for all comparisons).

Regarding the criteria for DCD donor hearts used in transplantation, Madan said teams are highly selective.

“This is quite expected as heart transplantation from DCD donors is a new emerging practice area in the US so heart transplantation centers are expected to be more cautious,” he said. “Second, donors with these types of characteristics are more likely to tolerate the mandatory warm ischemia which occurs during the procurement of hearts from DCD donors.”

Clinical outcomes following DCD transplantation were compared with 2,961 transplantations of patients who received a DBD heart. Compared with recipients of DBD heart transplantation, those who received a DCD donor heart had lower UNOS urgency status overall and were more like to have type O blood, “[which are] two factors that are associated with long waitlist times in the United States,” say researchers.

The median follow-up was 6.1 months, and the Kaplan-Meier estimates for 30-day and 6-month survival were 96.8% and 92.5%, respectively, for the overall cohort. In unadjusted and adjusted models, there was no significant difference in 30-day or 6-month survival between recipients of DCD heart transplantation and those who received a heart following the brain death of the donor.

In a propensity-matched analysis based on donor/recipient characteristics, there was no significant difference in post-transplantation survival in 126 recipients of DCD hearts and 252 recipients of DBD hearts.

Secondary outcomes included primary graft failure leading to death or retransplantation at 30 days follow-up, hemodialysis, and need for a permanent pacemaker. Again, there were no significant differences between the DCD and DBD cohorts. Median hospital length of stay was 16 days for both groups of patients.

Finally, the researchers looked at the potential impact of using DCD hearts in transplantation. Based on the total number of adult DCD donor referrals with complete information, they estimated that anywhere from 18.4% to 22.7% of DCD donor hearts could be used for transplantation, translating into 559 to 692 usable organs. Even if just half of these were ultimately used, say researchers, it would mean an additional 300 organs per year available for patients in need of a new heart.

Challenges Remain

In an editorial, Francis Pagani, MD, PhD (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor), points out that the number of heart transplants in the US has increased from 2,322 in 2011 to 3,658 in 2020. The growth in the number of available hearts—which still falls short of need—is partly the result of the opioid epidemic but also due to loosening the restrictive criteria for donors. For example, donor hearts from patients with hepatitis C are now allowed.

For Pagani, the new UNOS data support the use of DCD donors for heart transplantation as another strategy to increase the donor heart pool. The early results are in line with other international efforts using DCD donors, he writes, though widespread implementation faces a range of challenges, related to harvesting technique, understanding of warm ischemia tolerability, and costs.

One concern, Pagani notes, is that the higher cost and use of resources might limit DCD heart transplantation to larger and richer centers, which could increase existing regional disparities in access to heart transplantation.

To TCTMD, Madan acknowledged many of the same hurdles in this field, especially the unknowns around viability in the face of warm ischemic injury. There is considerable debate in the transplant world about the appropriate threshold for blood pressure or oxygenation below which myocardial ischemia begins.

This week, physicians and surgeons at the University of Maryland School of Medicine made global headlines when they implanted a genetically altered porcine heart into a 57-year-old man, a story that points, at least potentially, to yet another future pool of donor hearts to meet the growing demand.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

Madan S, Saeed O, Forest SJ, et al. Feasibility and potential impact of heart transplantation from adult donors after circulatory death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;79:148-162.

Pagani FD. Heart transplantation using organs from donors following circulatory death: the journey continues. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;79:163-165.

Disclosures

- Madan reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Pagani reports serving as a scientific advisor for FineHeart and CH Biomedical (both uncompensated).

Comments