Which Modality and When? New Guidance for Cardiac Imaging in COVID-19

Using the appropriate test can aid diagnosis but also lead to changes in management that may improve patient outcomes.

Uncommon cardiac presentations, unstable patients, limited resources, and exposure risks to personnel—COVID-19 poses a range of complicating factors and special considerations for cardiac imaging. Now, a multispecialty review commissioned by the Cardiovascular Imaging Leadership Council of the American College of Cardiology summarizes the available evidence and offers guidance for multimodal imaging in the setting of cardiac indications and confirmed or possible SARS-CoV-2 infection.

“In general, all of the societies have been putting out documents related to how to use their technique in the setting of COVID-19, whether that is related to [personal protective equipment] requirements or whether that is related to clinical guidance,” senior author and council chair Marcelo Di Carli, MD (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), told TCTMD. “We felt that it might be helpful for clinicians out in the field to get an integrated expert view bringing in all the opinions, not just one subspecialty, and arriving at some consensus about what we think is most effective in this disease.”

Authors on the document include “experts in imaging, but also experts in critical care cardiology, in heart failure, in interventional cardiology, and in general cardiology,” he added, “so it’s a really broad view of the field: of how not just the imagers but also the nonimagers view the relative utility of a given technique, given a set of clinical presentations.”

The review, with first author Lawrence Rudski, MD (Jewish General Hospital, McGill University, Montreal, Canada), was published this week in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

A View of the Heart in COVID-19

Cardiac involvement is common in COVID-19, and the typical workup includes the standard combination of history, physical exam, lab tests, electrocardiography, and chest X-ray. These, say the authors, likely suffice if cardiac biomarker results are normal/low and static.

Where BNP/NT-proBNP point to myocardial stress or troponin tests point to cardiac injury, “selective imaging might be considered if clinical judgment dictates,” they advise. Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) or standard echocardiography when POCUS is not available is often the best place to start.

From there, the review offers guidance for the most common scenarios encountered in patients with indicators of cardiac involvement alongside confirmed or suspected COVID-19 in the acute setting: chest discomfort accompanied by electrocardiographic changes, acute hemodynamic instability/shock, and new-onset left ventricular dysfunction.

In the first scenario—a common one in COVID-19—patients whose symptoms raise a clear clinical concern for ST-elevation ACS should be referred for emergent angiography without additional imaging, the document advises. However, in a patient with equivocal symptoms or an atypical/unequivocal ECG test, as well as a situation in which a patient delayed seeking help for a presumed ACS, POCUS would be an appropriate first test to assess for functional abnormalities and reduced ejection fraction. Of note, the authors say, myocarditis and myocardial injury in this viral illness may produce regional wall abnormalities.

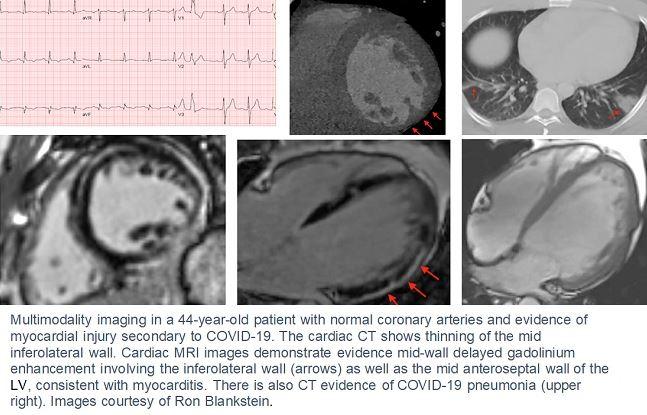

In a patient with chest pain and ST-elevation but without clear evidence of STEMI, cardiac CT angiography is “preferred as an initial advanced imaging study to rule out ACS,” the authors say. On the other hand, if a patient has an acute MI presentation but is found to have normal or nonobstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA), cardiac MRI may help with alternate diagnoses including myocarditis, embolic infarction, and Takotsubo. For the latter, in the absence of coronary obstruction but in the presence of echocardiographic findings consistent with stress cardiomyopathy, additional imaging may not be needed, they write. Also of note: in stable patients with previously established CAD who present with chest pain, it may be feasible and appropriate to delay further testing until their COVID-19 infection clears.

Hemodynamic Instability and Dysfunction

In the second scenario—a patient in shock or hypotension—hemodynamic instability can be a marker of a wide range of functional disorders, with and without myocardial injury or myocarditis. In their review, the authors detail the range of shock presentations to be on the lookout for with COVID-19 and their potential mechanisms. A patient presenting with STEMI accompanied by hemodynamic instability should proceed directly to angiography and reperfusion without additional imaging, Di Carli and colleagues recommend. In the absence of STEMI, physicians should have “a high index of suspicion” for pulmonary embolism in the setting of COVID-19, especially if accompanied by sinus tachycardia, RV strain, or rising D-dimer. In this scenario, they say, contrast CT is the “modality of choice.”

For the third scenario—new LV dysfunction but no shock or hypotension—the underlying cause may be prior undiagnosed dysfunction or a more urgent, new-onset condition such as fulminant myocarditis. The review details echocardiographic indicators for the different underlying mechanisms, situations warranting a “full” echo as opposed to POCUS, and the role of positron emission tomography (PET) when MRI results are unclear or cannot be performed.

Into the Future

In the fourth clinical scenario, Rudski et al offer cautious advice for imaging during the subacute/chronic phase of COVID-19—a period in which the late/lasting effects of the illness are unknown and the role of cardiac biomarkers has not been established. Elevated BNP/NT-proBNP “might be helpful” for determining the presence and severity of cardiac damage and dysfunction. Here, the authors single out repeat echocardiography as an important tool for patients who have new-onset LV dysfunction in the hospital. MRI may be important for determining any lasting signs of myocardial injury in the setting of normal heart function. The key, they say, is that any signs of heart rhythm disturbances, chest pain, or heart failure should be followed up according to existing guidelines.

Speaking with TCTMD, Di Carli emphasized that any late evaluation of chronic cardiac injury, as with any type of imaging follow-up, should be driven by symptoms rather than COVID-19 curiosity.

“There’s a lot of speculation about what the disease will bring in the chronic phase,” Di Carli observed, singling out the flurry of research around microthrombi and whether acute injury to the microcirculation will translate into chronic cardiac injury. He himself is involved in research projects employing PET imaging and MRI in COVID-19 survivors, with the aim of linking imaging findings back to biomarker results during the acute infection. Investigators aim to also use single-cell analyses to illuminate the culprit inflammatory pathways responsible for specific abnormalities documented on later imaging.

Outside of the research setting, however, Di Carli and co-authors do not recommend any kind of follow-up imaging unless clinically indicated. “This was a topic of very active and lively discussion in the group, because as imagers we always want to follow up and see resolution, etc. But whatever we do needs to be guided by some kind of clinical question: what would we do with that information and how would that change our approach to management? We need to balance the desire to know versus the need to use that information to make an active change in the management plan.”

These are covered under the umbrella of existing guidelines, he said. “In the absence of evidence, all we could agree on was that we will guide the use of imaging by traditional ways in which we already deal with chest pain, arrhythmia, or heart failure, and routine follow-up is something that we don’t advocate.”

Photo Credit: Ron Blankstein, MD

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full BioSources

Rudski L, Januzzi JL, Rigolin VH, et al. Multimodality imaging in evaluation of cardiovascular complications in patients with COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Rudski reports having minor stock holdings in General Electric outside of a managed portfolio.

- Di Carli reports institutional grant support from Gilead Sciences and Spectrum Dynamics, and consulting income from Janssen and Bayer.

Comments