Atrial Septal Aneurysm, Not Shunt Size, Tied to Recurrent PFO-Related Stroke

Experts caution against any blanket exclusion of patients with large shunts when making decisions about PFO closure.

The presence of an atrial septal aneurysm (ASA), but not shunt size, is associated with recurrent stroke in patients with a patent foramen ovale (PFO) who have already suffered a PFO-related stroke, according to a new pooled analysis.

“These results will help to better identify those patients with a high risk of stroke recurrence under medical therapy,” write Guillaume Turc, MD, PhD (Université de Paris, France), and colleagues. “It is plausible that such patients derive the most benefit from PFO closure, but this hypothesis should be formally confirmed in an individual patient data meta-analysis of all randomized controlled trials of PFO closure versus medical therapy.”

However, Zachary Steinberg, MD (University of Washington Medical Center, Seattle), who was not associated with the study, told TCTMD that these results should not give license to practitioners to only perform PFO closure on so-called “high-risk” patients.

“I take issue with that because right now I'd say we don't have enough evidence to suggest that only high-risk patients are going to benefit,” he said. “These are patients with known stroke and known PFOs and no other obvious cause. We know that the fallout from stroke, the clinical consequence, can be massive. . . . The emotional impact that it has on people, especially younger people, who have had a stroke, not knowing how to prevent it in the future, can be substantial.”

Although not foolproof, PFO closure has been shown to have “very good efficacy,” Steinberg added.

“I think that moving away from ‘What does the shunt look like based on bubbles?’ will be important, and I have personally never found that to be a major influencer on whether or not I bring someone for PFO closure for secondary stroke prophylaxis,” he said. “I look at their clinical story, I discuss with referring neurologists, and to some degree look at anatomic information, but I do it more with an eye toward what type of device I would use. If someone has a PFO who has no other great explanation and I'm in consultation with the neurologist that can also provide no additional clear explanation, I think offering PFO closure given its very low risk nature continues to be appropriate.”

Only ASA Associated With Recurrent Stroke

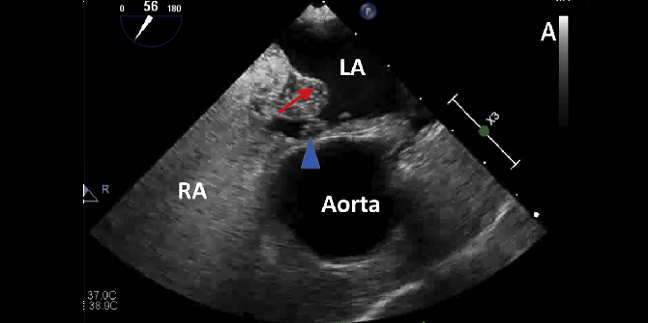

For the study, published in the May 12, 2020, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the researchers pooled individual data from 898 patients (mean age 45.3 years) enrolled in two prospective observational studies and the medical arms of two randomized trials—DEFENSE-PFO and CLOSE. Using transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), the researchers diagnosed an ASA if the septum primum excursion was ≥ 10 mm, while a large PFO was defined by the appearance of more than 30 microbubbles in the left atrium within three cardiac cycles after opacification of the right atrium. Overall, 19.8% of patients were classified as having ASA with a large PFO, 7.9% had ASA with a nonlarge PFO, 44.2% had a large PFO without ASA, and 28.1% had a nonlarge PFO without ASA. All patients received either antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy.

Over a median follow-up period of 3.8 years, the rate of recurrent ischemic stroke was 5.2%. There was significant heterogeneity across all four studies with respect to PFO size, but no evidence of heterogeneity related to the effect of ASA on recurrent stroke risk.

The incidence rate of recurrent ischemic stroke was heightened for patients with an ASA regardless of PFO size but not in those without ASA.

Recurrent Ischemic Stroke Incidence by PFO Presentation

|

|

Incidence of Recurrent Stroke per 100 Person-Years |

95% CI |

|

ASA |

|

|

|

Large PFO |

2.4 |

1.6-3.8 |

|

Nonlarge PFO |

2.7 |

1.3-5.5 |

|

No ASA |

|

|

|

Large PFO |

0.6 |

0.4-1.1 |

|

Nonlarge PFO |

1.3 |

0.7-2.3 |

After adjustment for age, hypertension, antithrombotic therapy, and PFO anatomy, the researchers showed that ASA was independently associated with recurrent stroke (adjusted HR 3.27; 95% CI 1.82-5.86), but large PFO was not (average adjusted HR across studies 1.43; 95% CI 0.50-4.03).

Mechanism Not Yet Clear

“It is not yet clear how the presence of ASA affects the risk of stroke in the setting of PFO,” Turc and colleagues write. “One hypothesis is that the presence of ASA may help facilitate paradoxical embolization through a PFO, by leading to a more frequent and wider opening of the PFO channel or by hemodynamically directing flow from the inferior vena cava towards the foramen ovale. . . . Other potential mechanisms have been postulated, including thrombus formation on the surface of the ASA or left atrium and left atrial appendage dysfunction, which might contribute to an increased propensity for the development of in situ thrombus and subsequent embolization.”

The findings cannot completely exclude the possibility that large PFOs are related to stroke recurrence due to wide confidence intervals, the authors state. “It is therefore possible that larger studies yield a significant result. However, if this relationship exists, it is likely less strong than the association between ASA and recurrent stroke.”

Practically speaking, they add that the results “stress the importance of TEE in the etiological work-up of ischemic stroke in adult patients up to at least 60 years of age to ensure optimal detection of ASA, even in patients with nonlarge PFO. They stress the findings “should not be interpreted as a demonstration that patients without ASA will not benefit from PFO closure. Only an independent patient data meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials could specifically address this question.”

Steinberg seconded this argument but wasn’t sure that kind of further study is necessary. “We have pretty good data to suggest atrial septal aneurysm plays a role,” he said. “I think we have reasonable data and it makes anatomic sense. They're showing something that we all kind of intuitively believe to be true and it's repeatedly shown to be true,” he said.

Rather, the next step should be focused on predicting which patients have high-risk PFO features that will benefit from primary prevention, Steinberg said.

“We know that 25% of people have PFOs, but we don't know how many have atrial septal aneurysms and large eustachian valves, and if it's a very small portion of people, it may be the same people who are going to be at risk for stroke for the future,” he said. “These are big concepts—very hard to determine—but I think as more and more of this literature comes out of trying to refine who's at high risk, . . . does this mean we're not going to be closing PFOs in people who don't have these features for secondary prophylaxis? Or does this mean that we're going to really look at patients who have yet to have their strokes, find that they're very high risk and potentially avoid a catastrophic event?”

More Data, Less Opinion

In an accompanying editorial, David E. Thaler, BM, Bch, DPhil (Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, MA), noted that “an important strength of this study is the inclusion of the older Korean patients, who made up one-quarter of the population being reported. They had a mean age of 54 years—almost a decade older than subjects in the clinical trials.”

But in answer to why the study failed to show an association of large shunts with recurrent stroke, Thaler said, “Sometimes, we know that something is so but do not know why. . . . Other times we think we know why something is so even before knowing that it is. It has been almost axiomatic that ‘larger PFO shunts are riskier.’ It certainly makes sense—more bubbles, more shunting, and so, a greater likelihood that an embolism will get towed along in the stream. We know why it is, but it has been harder to show that it is. Maybe the reason for this is that it is not riskier.”

Similar to Steinberg, Thaler said “this finding should lead us to be cautious about concluding too firmly that large shunts are the dangerous ones. Even more caution should be given before proposing dogmatically that ‘small PFOs do not need to be closed.’ Withholding a proven treatment from an individual should be done with a firm evidentiary basis rather than with intuition.”

Ultimately, he concludes, “the observations from this paper provide helpful data on the predictors of recurrence. More data, and less opinion, that inform the ongoing debate about patient selection for PFO closure are badly needed, and greatly welcomed.”

Photo Credit: J Am Coll Cardiol. Central Illustration (adapted).

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Turc G, Lee J-Y, Brochet, et al. Atrial septal aneurysm, shunt size, and recurrent stroke risk in patients with patent foramen ovale. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2312-2320.

Thaler DE. Risk management: “high-risk” PFOs come into partial focus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2321-2322.

Disclosures

- The CLOSE trial was funded by the French Ministry of Health.

- The DEFENSE-PFO trial was funded by a research grant from the Cardiovascular Research Foundation, Seoul, South Korea.

- Turc reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Steinberg reports serving as a consultant for Medtronic, conducting PFO research (no personal funding) for Gore, and serving as a course director and proctor for PFO closure for Abbott.

- Thaler reports serving on the steering committees of the RESPECT trial, the CATALYST trial, and the PFO-Post Approval Study (Abbott).

Comments