Cardiopulmonary Tests Urged for Lasting Fatigue, Dyspnea After COVID-19

Up to one in five patients who recover from COVID-19 have lingering symptoms months later, with dyspnea seen in half.

Patients who have unexplained dyspnea months after recovering from COVID-19 often have objective signs of breathing problems on cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) and meet criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a small, single-center study suggests.

Overall, 88% of the patients had abnormalities “consistent with dysfunctional breathing, resting hypocapnia, and/or an excessive ventilatory response to exercise,” while 58% had evidence of circulatory impairment, according to researchers led by Donna Mancini, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY).

Moreover, nearly half (46%) met criteria for ME/CFS, they report in a study published in the December 2021 issue of JACC: Heart Failure.

“In patients who have persistent dyspnea and there’s no clear etiology, they all should have a cardiopulmonary exercise test,” Mancini told TCTMD, noting that “patients who have dysfunctional breathing can undergo breathing retraining and perform certain exercises to decrease their hyperventilation and to relieve their symptoms.”

CPET in Long COVID

The findings provide insights into the issues faced by patients with postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), who are often called long-haulers. Roughly 15% to 20% of people who recover from COVID-19 have lingering symptoms months later, and dyspnea is observed in about half of this group, often accompanied by normal results on pulmonary and cardiovascular tests, Mancini said.

Because CPET is frequently used to investigate unexplained dyspnea, Mancini decided to explore its use specifically in patients with long COVID. The study included 41 patients (mean age 45)—23 women and 18 men—who had PASC involving unexplained dyspnea an average of 8.9 months after recovering from COVID-19 who were referred by cardiologists or pulmonologists for CPET. Investigators also assessed criteria for ME/CFS, which has symptoms that overlap with those associated with PASC.

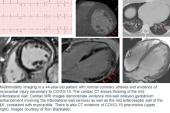

All patients had normal pulmonary function tests, CT scans, chest X-rays, and echocardiograms, and the average LVEF on transthoracic echocardiography was 58%. The patients developed new and persistent shortness of breath more than 3 months after recovering from COVID-19.

The vast majority of patients had ventilatory abnormalities on CPET, the investigators found. “They were hyperventilating, they were taking shallow breaths, and some of this pattern of breathing can contribute to their underlying shortness of breath,” Mancini said.

This test today tells you where they are, and it may help provide them with the help they need. Antonio Abbate

Most patients (58.5%) had a peak oxygen consumption below 80% predicted, and among this subset, all had a circulatory limitation to exercise. Of the remaining 17 patients with normal oxygen consumption, 15 had other ventilatory abnormalities, including dysfunctional breathing or an increased respiratory rate.

It remains to be seen whether detection of these abnormalities and implementation of some type of intervention (such as breathing retraining) will relieve symptoms in patients with persistent dyspnea after COVID-19, and that will be the next step in the research, Mancini said.

In addition, “further study is needed with patients undergoing CPETs with hemodynamic and arterial gas measurements,” she and her colleagues write. “Correlation of CPET findings to lung and cardiac imaging should also be performed.”

But for now, guidelines for managing the chronic phase of COVID-19 should include use of CPET, Mancini suggested, adding that testing can be safely performed even in patients with severe symptoms.

‘Welcome Data’

Commenting for TCTMD, Antonio Abbate, MD, PhD (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond), said these are welcome data, as clinicians have already been using CPET to evaluate undifferentiated symptoms of exercise intolerance or dyspnea both in the broader population of patients and in those recovering after COVID-19.

CPET is available in many hospitals and should already be used for patients with unexplained symptoms after an initial workup, Abbate added. “It’s, in my opinion, underutilized already,” he said. “And so I think that this study increases the awareness of the value of this test in patients with poorly understood symptoms, including patients with COVID or post-COVID.”

The study also shows, in this specific group of patients at least, that the reported symptoms can be tied to objective measures reflective of cardiorespiratory fitness, identifying potential targets for intervention, Abbate said. CPET “is likely to reveal subclinical abnormalities in the respiratory, cardiovascular, or muscular systems that may explain the dyspnea,” he commented. “It should be in the toolbox of physicians that are investigating persistent dyspnea in patients that have a normal initial evaluation, which is exactly [how you would use] this test in other conditions even independent of COVID.”

One note of caution about the findings, Abbate said, is that a definitive link cannot be established between COVID-19 and the CPET findings because there were no pre-COVID-19 measures available. “While you may expect that this is related to it, you can’t really assume causality,” he said, adding that it isn’t realistic to expect that all of these patients had completely normal function prior to the infection.

“Nevertheless, this test today tells you where they are, and it may help provide them with the help they need,” Abbate said.

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Mancini DM, Brunjes DL, Lala A, et al. Use of cardiopulmonary stress testing for patients with unexplained dyspnea post-coronavirus disease. J Am Coll Cardiol HF. 2021;9:927-937.

Disclosures

- Mancini reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments