Gatekeeper CTA Strategy in Stable Chest Pain Still Needs Honing

UK numbers hint that overuse of additional invasive imaging is still an issue, with revascularization only following half of ICAs.

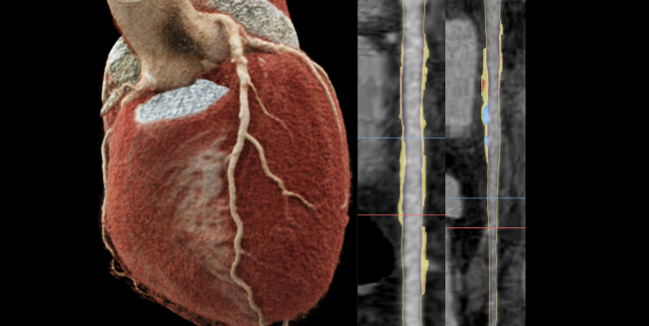

A 3-dimensional volume rendered image of a cardiac CTA scan (left). Coronary arteries from CTA with atherosclerosis in the coronary tree via a color overlay (right). Photo credit: Andrew Choi.

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CTA) can safely negate the need for further testing in about three-quarters of patients with new-onset chest pain, according to a new UK-based analysis. Nonetheless, invasive procedures are still overused in a subset of patients, with half of the patients referred for additional invasive imaging not undergoing revascularization, according to the researchers.

In the United Kingdom, the 2016 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines made CTA a first-line test for the evaluation of stable chest pain, as did the European guidelines in 2019. CTA doesn’t have the same support in current US guidance, but proponents of the test in this setting are optimistic that may change in guidelines due out later this spring.

“What I see in my day-to-day work is or has been perhaps a potentially excessive use of invasive coronary angiography after patients have already had one angiogram, albeit a noninvasive angiogram,” lead author Gareth Morgan-Hughes, MD (University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust, England), told TCTMD. “Most invasive angiograms are not resulting in the patient's getting revascularization and perhaps are unnecessary.”

The findings confirm what has been seen before, Andrew Choi, MD (The George Washington University, Washington, DC), who was not involved in the study, told TCTMD. “It's compatible with prior work, especially in the United Kingdom, that suggests about half of the patients who are undergoing invasive angiography after the initial CCTA won't have revascularizable disease,” he said. “This also parallels what happens in the United States, and reducing unnecessary invasive angiography provides a really important opportunity for us to continue to improve our patient-centered care.”

“What I think is happening for a lot of the patients who did go for invasive angiography is that they will have had atheroma lesion or lesions, let's say more than 30% to 40%, and symptoms,” he said. “And the problem with the CTCA anatomical approach to these patients has always been that finding atheroma does not necessarily explain the symptoms. So, you generate a large group of people who have little or no atheroma and you can then be relatively confident that they don't need revascularization. But you also generate a lot of people who do have atheroma who then the question arises: can you assume that atheromatic lesion is causing their symptoms?”

Modest ICA Rate

For the study, which was published online February 23, 2021, in Open Heart, Morgan-Hughes and colleagues prospectively looked at 5,293 patients (50% female) from nine centers in the United Kingdom who underwent CTA between January 2018 and March 2020. Overall, 96% of scans were diagnostic, and 12% of patients subsequently underwent ICA; of the latter group, 48% did not undergo revascularization.

What I see in my day-to-day work is or has been perhaps a potentially excessive use of invasive coronary angiography after patients have already had one angiogram, albeit a noninvasive angiogram. Gareth Morgan-Hughes

About three-quarters (73%) of patients were deemed to have a CAD-RADS score of 0 to 2, with only 1% of them undergoing ICA. Among the 10% with a CAD-RADS score of 3, 23% underwent ICA, with 26% of them eventually being revascularized. Finally, 64% and 74% of patients with CAD-RADS scores of 4 (10%) and 5 (2%), respectively, were revascularized.

In total, 8% of the population underwent functional testing following the CTA, and 96% of these patients did not undergo revascularization. Also, CT-based fractional flow reserve (FFRCT) was used in only 4% of patients.

Morgan-Hughes said he was “pleasantly surprised” at the modest rate of ICA after CTA, especially among patients with moderate stenosis. “That's something that's probably improved to a certain extent during the last couple of years while we've been doing the work. Certainly, it’s probably a much lower rate than you see in North America,” he said, adding that they plan to publish the data based on sex differences, which may be of even more interest.

Additionally, the data show that CT is “a very effective way of triaging chest pain patients,” Morgan-Hughes said. However, “traditionally, cardiologists of my generation have been brought up believing that catheter angiography is the gold standard, and have been brought up with treadmill as the noninvasive test and maybe nuclear or functional imaging, and when that's abnormal, the default position has been to do an invasive angiogram. I think some cardiologists are still stuck in their ways in that regard.”

As for any cost advantage, “the NICE approach only works if you follow it to the letter,” he said. “If you take a CT at the outset and then you go on doing a cath because you want to check the findings or you do a cath that doesn't change management, then all the cost savings goes out the window. That's the other potential driving force behind wanting to publish this type of data is just to get people to think about whether they do need another test and do they need to spend that extra amount of money.”

Going forward, Morgan-Hughes said he would like to see future research look at these modalities in real-world practice as well as “more debate about the use of functional imaging and FFRCT for intermediate stenosis. . . . I'd be a bit concerned about seeing widespread use of FFRCT at 600 pounds sterling a go.”

‘An ISCHEMIA-Trial World’

Importantly, Choi noted that “we now live in an ISCHEMIA-trial world,” referring to the pivotal 2019 study that showed no difference in endpoints with an invasive revascularization strategy versus optimal medical therapy alone for patients with stable CAD and moderate-to-severe ischemia.

“If you can exclude left main coronary disease by CCTA, it gives you an opportunity to maximize medical therapy and treat [according] to symptoms without the need for further testing, either functional or invasive testing, and only reserve downstream functional testing to affirm the cause and treat refractory chest pain symptoms,” Choi said. “That's really important in that it allows us to optimize the medical therapy for these stable chest pain patients.”

This study did not report the number of patients with left main disease or high-risk anatomy, he noted. “I think those patients would benefit from revascularization; however, many of those patients who have obstructive CAD but without high-risk anatomy may be able to be optimized through medical therapy alone without the need for any further downstream testing.”

As for why some physicians continue to perform ICA so often, Choi said they are “continuing to apply a 20th century paradigm of stenosis in a 21st century world of atherosclerosis. We can use these findings from CCTA to reduce downstream testing costs. We can personalize the approach. We can identify atherosclerosis and focus on all these preventative strategies that now include lifestyle interventions, statins, icosapent ethyl, PCSK9 inhibitors, colchicine, NOACs, and novel agents that are all shown to result in plaque inhibition. And I think it is just incumbent on these centers to continue to adapt the best, evidence-based approach.”

For those in the United States, this study “reminds us that using a national registry as done in the UK presents an opportunity to enhance cost-effective, broad-based research into our strategies for chest pain through CCTA while also allowing for important quality improvement initiatives,” Choi added. “The analysis points out that we need to continue to improve access to these CCTA-oriented technologies and care, we need to continue to devote resources to increasing capable readers through educational efforts. And then I think that our future in the 21st century is to apply these findings for patient-centered, atherosclerosis imaging to ask how do we now incorporate these approaches in an era of digital health, in an era of artificial intelligence, that will allow for enhanced identification of coronary disease while reducing downstream testing.”

FORECAST and FFRCT

Curzen pointed out that “CTCA very commonly doesn't give definite results about the significance anatomically of the lesion. So I'm sure the cardiologists who offered invasive angiography for some of the patients did it because they weren't sure how severe the lesions were.”

Findings from the FORECAST trial, led by Curzen, will inevitably change the paradigm, he continued. FORECAST indicated that FFRCT reduced the use of invasive angiography, but at an increased up-front cost that was not offset by a reduction in downstream tests. “Even when you have FFRCT, the conversion rate from the invasive angiogram to the revasc is quite wide, which is why I say I'm not at all surprised by the current results because most of these patients didn't have FFRCT,” he said. “We now have learned an algorithm thanks to SCOT-HEART and FORECAST, which is patients should have a CTCA up front. . . . If they continue to get angina, then I think it would be entirely plausible based on FORECAST that retrospectively their CTCA is sent for FFRCT analysis. If they have ischemia and their symptoms are ongoing, the FFRCT analysis would confirm whether or not there's ischemia and if so where it is. A plan could then be made with the patient about whether they want to consider revasc and what type of revasc is likely.”

This strategy can reduce the rate of ICA by 22% according to FORECAST, “but you only reduce it by 22%,” Curzen said. “This is why I wonder whether the conclusion that there's a lot of ICA overuse in this observational study may be a bit of an exaggerated finding, because even when you have as much FFRCT as you need and want, you still end up doing quite a lot of ICA and you still don't revascularize all of those patients by any means.”

In the future, he continued, “it may be possible to bypass ICA completely in the patients that FFRCT suggests need bypass surgery. Surgeons increasingly will be happy to take people on for bypass surgery based on the combination of CTCA with FFRCT, so those patients won't need an invasive angiogram at any stage. They'll just go to surgery. And the PCI ones, if they're committed to PCI because the symptoms haven't settled despite optimal medical therapy, they won't need a pressure wire because they've already had FFRCT to tell us which vessel to aim at.”

Regionally, Curzen noted that even within the UK, use of both CTA and FFRCT still widely varies based on resources and expertise. “Within another few years, most trusts will be compliant with these guidelines, so most patients will get CTCA up front, and by then I think a combination of evidence including FORECAST will probably indicate that they don't need another test until they've had a trial of optimal medical therapy, which is what ISCHEMIA has told us loud and clear and what COURAGE told us 10 years before that,” he said.

In the future, CTCA should appropriately be the frontline test for this population “because it allows very rapidly for them to be put on disease-modifying optimal medical therapy if they've got atheroma, and we know that's a very good thing,” Curzen said. “What happens after that, assuming that you eliminated the people with really severe angina and the people with left main, is I think that if they have breakthrough symptoms, they should probably be offered FFRCT retrospectively. . . . Then the people who are FFRCT-positive probably will get an invasive angiogram and will get revascularized one way or the other, but another fifth of them will have been eliminated from needing that. I think that pathway is probably the one that will emerge in the next year or two.”

Photo credit: Andrew Choi

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Morgan-Hughes G, Williams MC, Loudon M, et al. Downstream testing after CT coronary angiography: time for a rethink? Open Heart. 2021;8:e001597.

Disclosures

- Morgan-Hughes reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Curzen reports serving as the chief investigator of the FORECAST trial, which was funded by an unrestricted research grant by HeartFlow.

- Choi reports holding equity in Cleerly.

Comments