Higher Gradient After Tricuspid TEER Not Harmful at 1 Year: TriValve Registry

The study provides insight into “how far we should go in treating TR . . . and which gradients we should accept,” Andrea Scotti says.

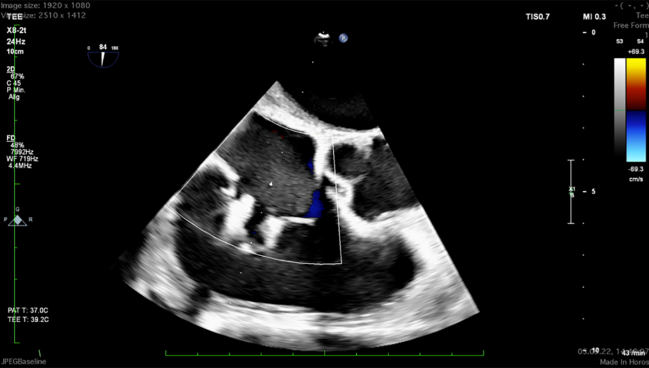

Photo Credit: Adapted from von Bardeleben RS. Tricuspid TEER is the first choice to treat TR – updates from bRIGHT and TRILUMINATE Pivotal. Presented at: TCT 2022. Boston, MA.

A higher tricuspid valve gradient at hospital discharge doesn’t seem to be detrimental to patients who’ve undergone transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER) for significant tricuspid regurgitation (TR), according to a retrospective analysis of data from the TriValve Registry.

By 1 year, patients with the highest gradients were no more likely to die or be hospitalized for heart failure (HF), researchers found.

“We know very little about the tricuspid valve, especially when it comes to transcatheter procedures,” said Andrea Scotti, MD (Montefiore Medical Center and Cardiovascular Research Foundation, New York, NY), who will be presenting the findings later today at the Technology and Heart Failure Therapeutics (THT) 2023 meeting in Boston, MA.

Mere weeks ago, at the American College of Cardiology/World Congress of Cardiology (ACC/WCC) 2023 meeting, the TRILUMINATE Pivotal trial added support to TEER’s use for treating symptomatic severe TR on top of prior results reported back in 2019 for the TRILUMINATE trial.

As with the mitral valve, TEER in the tricuspid involves weighing the goal of reduced regurgitation against the potential risks of higher gradients that come with narrowing the valve area.

Data from the mitral side have been mixed as to whether these increased gradients do in fact cause harm, Scotti pointed out to TCTMD—in the COAPT trial testing TEER in functional mitral regurgitation (MR) there were no ill effects of higher gradients on outcomes, but other studies have hinted that the etiology of the MR being treated has implications for how much gradients matter. For example, as reported by TCTMD, TVT Registry data recently presented at ACC/WCC 2023 drew a link between gradient and the 1-year risk of death and HF hospitalization in patients with degenerative MR.

In most patients with tricuspid valve disease, TR is functional and thus “more COAPT-like, so in our results we expected [to see] something similar to COAPT,” said Scotti.

Their study provides operators with knowledge to guide “how far we should go in treating TR and placing clips and which gradients we should accept,” he said. TR should be reduced as much as possible to “provide improved clinical outcomes in these patients who suffer from heart failure” and offer an alternative to diuretics, which have historically been the cornerstone of their care.

The TriValve Registry results were published online in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions with Scotti and Augustin Coisne, MD, PhD (Montefiore Medical Center and Cardiovascular Research Foundation; CHU Lille, France), as first authors.

Robert Smith, MBBS, MD (Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, London, England), commenting on the new study for TCTMD, said tricuspid valve gradient is something “we talk about quite a lot” in the context of tricuspid TEER. That’s because the threshold for what constitutes tricuspid valve stenosis severe enough to merit replacement, such as in a patient with rheumatic heart disease, is 5 mm Hg, similar to the gradients being seen “reasonably frequently” after tricuspid TEER, Smith noted.

Here in the TriValve data, the overall mean gradient was 2.3 mm Hg. Though some degree of gradient is inherent to a well-functioning heart, “that’s not nothing,” he said.

“The point,” Smith added, “is we’re inducing this apparent ‘stenosis’ and what we need to know is: does it have any impact on symptoms and does it have any impact, more importantly, on outcomes? So far—it’s interesting—the suggestion is no.”

TriValve Registry

Scotti, Coisne, and colleagues analyzed data on 308 patients from 24 centers who underwent TEER for significant TR, dividing them into quartiles by mean tricuspid valve gradient at discharge: 0.9 ± 0.3 mm Hg (n = 77), 1.8 ± 0.3 mm Hg (n = 115), 2.8 ± 0.3 mm Hg (n = 65), and 4.7 ± 2.0 mm Hg (n = 51). A total of 15 patients (4.9%) had gradients of 5 mm Hg or higher.

After multivariable adjustment, both tricuspid valve gradient at baseline and greater number of implanted clips each were associated with higher post-TEER gradient.

The vast majority of baseline patient characteristics were similar across the quartiles, with two exceptions: patients in quartile 4 were more likely than those in quartiles 1-3 to have previously undergone a left-sided valve intervention and less likely to be taking beta-blockers.

Quartile-4 patients tended to have more-severe preoperative TR, higher tricuspid valve gradient at baseline, a higher frequency of residual TR ≥ 3+, and lower procedural success rate than those in the lower quartiles. However, all of the quartiles saw similar benefits in terms of the TR reduction they derived from TEER.

Median follow-up lasted 174 days. On Kaplan-Meier analysis, there was no difference at 1 year in the primary endpoint of all-cause mortality and heart failure hospitalization, or in these outcomes individually, based on patients’ post-TEER valve gradients. The lack of association remained when adjusting for age, sex, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and residual TR severity after TEER.

TriValve Registry: Outcomes at 1 Year by Tricuspid Valve Gradient

|

|

Quartile 1 |

Quartile 2 |

Quartile 3 |

Quartile 4 |

|

Freedom From Death/HF Hospitalization |

65% |

70% |

60% |

66% |

|

Freedom From Death |

73% |

84% |

82% |

80% |

|

Freedom From HF Hospitalization |

72% |

79% |

64% |

69% |

Additionally, NYHA functional class improved for both patients in quartile 4 and those in quartile 1-3. At 30 days after TEER and at last follow-up, NYHA class III-IV was equally prevalent across quartiles.

Scotti cautioned that their analysis only captures outcomes through 1 year and that the sample size of patients with high gradients was small. “I don’t want people to misinterpret these results [by] saying we should clip as much as possible, even for gradients up to 15 [mm Hg]. This is not the message we want to give,” he said, adding, “It will be great to see at longer-term follow-up if these results change.”

On the other hand, “residual TR—more than moderate—was always associated with adverse outcomes,” Scotti observed.

What Counts as High?

One task going forward will be setting the bar for how much tricuspid valve gradient is acceptable post-TEER, both Scotti and Smith said.

European guidelines say a mean echocardiographic gradient of ≥ 5 mm Hg qualifies as significant native valvular tricuspid stenosis, the paper notes. When tricuspid stenosis is treated by surgery, mean gradients of biological prostheses range between < 6 to 9 mm Hg. Earlier studies of tricuspid TEER, meanwhile, used a cutoff of > 3 mm Hg, which didn’t appear impactful in the TriValve analysis.

Smith noted to TCTMD that there are two possible explanations for why high tricuspid valve gradients aren’t connected to worse results: it could be simply that patients can tolerate them without problems or it may be that the current criteria for tricuspid stenosis aren’t sufficiently detailed on the higher end of the spectrum.

If a gradient of 4 or 5, which was previously in the severe range, doesn’t have any clinical sequelae, what’s the point of grading it. Robert Smith

“With the advent of tricuspid TEER, we’re now seeing lots of people with gradients of 3, 4, 5 across the tricuspid valve, which didn’t exist previously. Just as tricuspid regurgitation was regraded to include ‘torrential’ and ‘massive’ above ‘severe,’ should we be potentially regrading tricuspid stenosis?” he suggested. “Because if a gradient of 4 or 5, which was previously in the severe range, doesn’t have any clinical sequelae, what’s the point of grading it? What’s the point in having a grade if you don’t do anything about it?”

A gradient of 6 or 7 mm Hg might be clinically relevant, Smith proposed.

He drew attention to the equivalent symptoms among the TriValve quartiles. “What it tells me is perhaps we can be a bit bolder in treating these patients [and] rather than stopping when we put a clip on and we get a gradient of 5, we leave it on,” he said. “We don’t want to leave tricuspid regurgitation behind. That, I think, is a bad thing to do.”

Smith said that, in terms of how to best manage a patient with elevated tricuspid valve gradient post-TEER, one consideration is whether they’re tachycardic, “because the filling time from the atrium to the ventricle is reduced. . . . With stenosis, you want to prolong that filling time [by being] a bit more aggressive with rate/rhythm control medication, beta-blockers, and so on. That’s the only thing I’d do differently.”

Future studies in this area are no doubt forthcoming, he noted. That said, since no signals of worsening symptoms or HF admissions are being seen at 1 year, Smith doesn’t expect to see the quartiles’ curves start to separate. Nor would there likely be any progression toward worse tricuspid valve gradients at a later date, he added.

Nevertheless, Scotti said they hope to extend their TriValve follow-up to 2 years and confirm their results for patients on the higher spectrum of tricuspid valve gradient in a larger population.

Note: Coisne and Scotti are research fellows with the Cardiovascular Research Foundation, the publisher of TCTMD.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Coisne A, Scotti A, Taramasso M, et al. Prognostic value of tricuspid valve gradient after transcatheter edge-to-edge repair: insights from the TriValve Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2023;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Coisne has served as a consultant for Abbott and received speaker fees from Abbott and GE Healthcare.

- Scotti has received consulting fees from NeoChord.

- Smith reports proctoring and consultancy for Abbott UK as well as consultancy GE Healthcare.

Comments