Many PFO Closure Patients May Be Treated Off-label

Off-label abuse is not limited to PFO closure, but it is an example that raises practical questions, Andrew Goldsweig says.

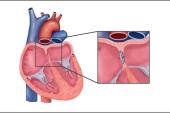

The population of patients undergoing patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure in the US doesn’t match those of the clinical trials that formed the basis of the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of these procedures, according to a new retrospective analysis.

More than one-third of patients treated between 2006 and 2019 did not have a documented stroke in the 2 years prior to having their PFO closed and almost one in five patients had atrial fibrillation at baseline, hinting at a substantial rate of off-label—and possibly unhelpful—use.

“I don't know whether it's a bad thing or a good thing; it depends on one's perspective on the numbers,” lead author Andrew M. Goldsweig, MD (Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, MA), told TCTMD.

PFO closure for cryptogenic stroke has a dramatic history. A spate of negative trials fueled criticism, especially from neurologists, that observational studies had blinded implanting cardiologists to the lack of benefit. Subsequent meta-analyses and longer follow-up indicating that the procedure was associated with a lower recurrent stroke risk led finally to FDA approval in 2016. While device closure has been examined for other indications, including more minor strokes and TIAs, as well as migraine and decompression sickness, studies have yet to demonstrate unequivocal benefit in those settings.

The current data, at a minimum, hint that some operators believe PFO closure could have wider usage than the current labelling sets out.

“This study reflects issues that are relevant to all medical devices,” Goldsweig said. “Ultimately, we believe that regulators and payers need to develop mechanisms to promote using devices for approved indications without stifling creativity. They want to facilitate clinical trials to investigate other possible indications, but they don't want to sign a blank check and have devices chronically used for other possible indications.”

Robert Sommer, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY), who served as the primary investigator for the RELIEF trial of PFO closure in migraine, cautioned against making too much of these results. “It is hard to critique all procedures that are ‘off-label’ just because they don't meet the very limited approval that we currently have through the FDA,” he told TCTMD. “As the number of procedures increases in any particular area, the insurance companies become much more observant and much more restrictive and do their best to minimize their costs. And I always feel like articles like this make it easier for the insurance companies to deny care to patients who might really need it.”

PFO Trends

For the study, which was published online this week in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, Goldsweig and colleagues looked at 5,315 patients (51.8% female) undergoing PFO closure with at least 2 years of information in the OptumLabs database between 2006 and 2019. Notably, 29.2% of patients were at least 60 years old an age older than participants in the any of the PFO-closure clinical trials.

The annual rate of PFO closure rose and fell with published negative and then positive data and then rose again once the procedure earned FDA approval. Overall, the rate of use grew from 4.75 per 100,000 person-years in 2006 to 6.60 per 100,000 person-years in 2019.

The primary indication for PFO closure as noted in the medical records was for stroke/systemic embolism (58.6%), but others included TIA (10.2%), migraine (8.8%), and other unknown reasons (22.4%). The reasons for closure remained relatively stable throughout the study period, but patients aged 60 and older as well as male patients less frequently had documented migraine.

Atrial fibrillation (AF) was present in 17.6% of patients at baseline, which is notable because device labelling urges caution in patients with this condition. FDA approval specified in the label that other causes of ischemic stroke—AF among them—be thoroughly investigated prior to PFO closure. Also, 11.9% developed AF after PFO closure, with more than half of the arrhythmias occurring within the first year. The latter finding is in line with prior research showing a spike in AF, albeit usually transient, after PFO closure.

Our medical system in general is sort of ripe for abuse because once a device is approved, you can do whatever the heck you want with it. Andrew M. Goldsweig

Goldsweig said that off-label device use is not unique to PFO closure, citing left atrial appendage occlusion as another procedure that is commonly used for patients with no documented contraindication to anticoagulation. “Our medical system in general is sort of ripe for abuse because once a device is approved, you can do whatever the heck you want with it,” he said.

However, Goldsweig said he chose to study PFO closure in this case because “it has really only one clearly approved indication, which is pretty easy to study. . . . I can tell you if somebody had a stroke in the last 2 years looking at their medical record. If they got care for having a stroke, they had a stroke. If they didn't get care for having a stroke, they probably didn't have stroke.”

When it comes to off-label device use, it’s not always clear whether it's abuse—whether for financial gain or other reasons—or done with the intention of truly trying to help, he continued. That’s why “professional societies can lead the way with guidelines,” he said. Registries can also “provide an outlet for creativity with a possibility to help science as opposed to just rampant off-label use. If you are doing something that is a little different than the guidelines but it's part of a registry and it's sanctioned by payers and regulators, first it gets paid for, but second, it doesn't just benefit that patient, the data are recorded so that this help change guidelines as opposed to random people in random places doing random things with no data getting recorded and amalgamated.”

Off-label Abuse or Benefit?

The study gives a good overview of how PFO closure is used in clinical practice, but it offers an “incomplete narrative” regarding why it is chosen, write Karen D. Orjuela, MD (University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora), and colleagues in an accompanying editorial. The study “underscores the problematic nature of using administrative claims to discern the intentions of medical providers. The use of OptumLabs Data Warehouse, while providing substantial data of a cross section of the US insured population, does not offer the relevant clinical insight into the intentions of the treating providers, often comprised of a multidisciplinary evaluation.”

The editorialists also highlight a number of “near-label indications” for PFO closure, including for those older than 60 and patients with TIA where data are nonexistent or limited, that might be beneficial pending a multidisciplinary team review of the patient.

Sommer agreed. The use of PFO closure is still “evolving,” he said. “We are still defining all of these indications.”

While the data to date are fairly conclusive in showing that patients with migraine do not benefit from PFO closure for that indication, Sommer agreed with the editorialists that it’s unclear what should be done for those with TIA.

“Patients with TIAs are a huge problem for us because not all TIAs are the same. Sometimes TIAs are a stroke; they just they don't have any evidence of damage on their MRI,” he pointed out. “So why is that any different if a patient becomes partially paralyzed, etc, and has stroke symptoms and gets a stroke evaluation and maybe even gets TPA in the emergency room? Why should that patient be treated any differently than somebody with a spot on their MRI?”

Ultimately, “to group all of these things together to make a point that there is too much off-label use going on, I think is really problematic,” he said, acknowledging that the attempt to reduce off-label abuse is laudable.

The editorialists, however, say that PFO closure today is likely performed in “a notable proportion” of patients who are unlikely to benefit. They write: “Goldsweig et al raise an important question: should there be a call for new paradigms in monitoring device utilization and patient outcomes in PFO, or is this a broader issue encompassing all medical devices and drugs post-approval?”

Some new data on PFO closure will soon come, including on new devices and indications as well as in older patients. In the meantime, Orjuela and colleagues say, a “postapproval system is needed to ensure high-quality data collection to guide expanded indications and clinical decision-making.”

For now, they argue, any “patient care decisions regarding off-label or near-label use of medical devices and medications . . . should be justified clinically, ethically, and legally.”

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Goldsweig AM, Deng Y, Yao X, et al. Approval, evidence, and “off-label” device utilization: the patent foramen ovale closure story. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2024;17:e010200.

Orjuela KD, Leppert MH, Carroll JD. Navigating the gray: the complex story of PFO closure utilization. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2024;17:e010581.

Disclosures

- Funding for this project was provided by the Great Plains IDeA-CTR (Institutional Development Award for Clinical and Translational Research) of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

- Goldsweig reports receiving consulting income from Inari Medical and Philips, speaking fees from Philips and Edwards, and research support from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the UNMC Center for Heart and Vascular Research.

- Orjuela reports receiving research support from the Bristol Myers Foundation and Abbott Laboratories.

- Sommer reports serving as the national PI for the RELIEF trial, sponsored by Gore Medical.

Comments