My Takeaways From ACC 2017: Even With a Sea Change, the Tide Takes Its Time

My prediction? The biggest impact of ACC 2017 won’t come from a trial, a drug, or a device, but from the faces we saw in the Main Tent.

WASHINGTON, DC—Forget the studies you saw presented at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Scientific Session 2017 or read about online, the gadgets in the exhibit hall, or the tweeting on Twitter. What if I told you the number one thing from ACC 2017 that will have the most impact on practice might not be a trial or a drug or a device?

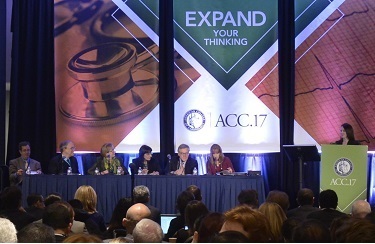

I noticed it first in the opening showcase session, where we got the FOURIER, SURTAVI, and SPIRE results: two female faces among the five panelists discussing the studies up front in the Main Tent. Not particularly unusual, perhaps, except that the chairs for the “deep dive” session that tackled these same studies the following day also were both women, with a third woman on the panel.

In fact, each of the late-breaking clinical trial and featured clinical research sessions at ACC 2017 had at least one woman, usually two, among the discussants. There was often a woman in the press conferences for these presentations. Three of the seven speakers for this year’s named lecturers were women, an honor that also put them on the dais at the ACC 2017 convocation ceremony. And speaking of convocation, that’s where Mary Norine “Minnow” Walsh, MD (St. Vincent Heart Center, Indianapolis, IN), was inaugurated as president—only the third time in the nearly 70-year history of the college that a woman has held this top spot.

I wasn’t the only one who was struck by a sense of change. Roxana Mehran, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), stopped me in the corridors to ask me if I’d noticed.

“Isn’t it amazing?” she said, as if women had learned to fly. (You can hear more from Mehran on this subject in her conversation here with TCTMD’s Yael Maxwell.)

But Pamela Douglas, MD (Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC), had a similar reaction, with a discernible twinkle in her eyes. No, she assured me, I wasn’t imagining things. Everyone was talking about it. “There was a definite feeling of inclusion this year—women being part of creating the content of the meeting, rather than just [being] consumers of education/information—that was palpably different from prior years,” she said.

Seeing Is Believing

Just how different was this year’s ACC? Typically I get back from a meeting with plans to spend my free time getting some fresh air, doing laundry, and eating a wide variety of vegetables. This time around, I spent it hunting down and e-leafing through old meeting programs. Relatively speaking, doing laundry is a lot more fun.

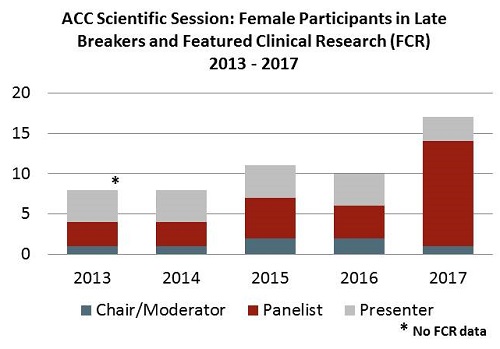

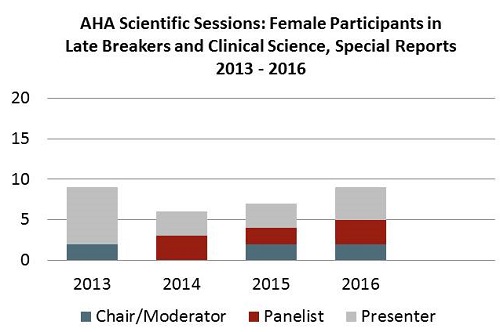

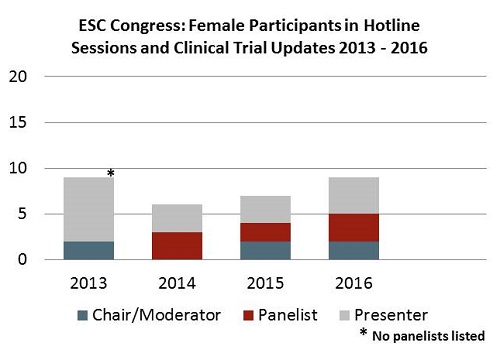

Mine was by no means a rigorous analysis—and my understanding is that both the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the ACC have been collating formal data to look at diversity within their organizations—but here’s the slice I looked at. I counted the number of male and female chairs/moderators and panelists for each of the late-breaking or “hotline” sessions at the ACC, ESC, and American Heart Association (AHA) conferences going back to 2013. I also tallied the numbers for the secondary “clinical trial updates” that each of these meetings also showcases. Finally, I figured I might as well also look at the balance of male and female presenters, although this obviously is a decision made by the research groups not the meeting planners.

The upshot: if you combine the chair and panelist categories, this year’s ACC had at least double the number of women in these roles than they’ve had in the last 5 years, nearly 50% more than the AHA has had most years, and nearly threefold higher than the ESC had in its best year.

Did someone leave the door unlocked for the secret passage that runs between the poster hall and the main stage? How did all these women get to the front of the room?

“No, no. This was definitely intentional,” said Athena Poppas, MD (Cardiovascular Institute of Rhode Island, East Providence), told me. Poppas was the ACC Annual Scientific Session chair for 2015 and 2016, a role that transitioned to Jeffrey Kuvin, MD (Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Manchester, NH), for this year’s meeting. Kuvin, said Poppas, has continued with the ACC’s strategic mission of increasing faculty diversity in the ACC program, with a focus on international faculty, junior faculty, and women.

According to Poppas, the goal was specifically to increase the visibility of women and people of color in the Main Tent sessions, and in the late-breaking sessions in particular. “We wanted to change the big picture that people see,” she said, “and Jeff certainly continued that [idea] of wanting to be sure that when you looked up at the stage—and there's 5,000 people looking up at the stage—that you see something that reflects our community.”

According to Poppas, women make up 15-20% of ACC membership, but the “gestalt feeling” (although they had no data initially to support their assumptions) was that women were not proportionally represented at the annual meeting. The shift this year was to not only increase the number of women chairing sessions or contributing as panelists, but to also have this happen in the big, high-impact sessions.

“I’ve had women I’ve never met in my life come up and say I decided to do X because I saw you, or I saw other women up there and it made me realize I can do that,” she said, noting that nonverbal cues do change behavior.

The Creaky Wheels of Change

A bigger question is whether you can draw a direct line between more women in the power seats at international meetings and better patient care. Poppas believes you can.

For starters, she said, “I think patients should have choice [of a male or female physician].” There’s also the oft-cited statistic that despite 50% of internal medicine graduates being women, this number shrinks to one-fifth in cardiology fellowships. “If you want the best and the brightest in a particular field, and 50% of your class is of a particular gender, then by limiting the leadership opportunities, you’re limiting the best and brightest being in that area,” Poppas stressed.

She noted that men, as well as women, stand to benefit from a better gender balance. Studies in business and academia have shown that working to increase the proportion of women in these settings has upped productivity, improved retention, and boosted revenues. "Changing the landscape benefits everyone," Poppas said. "I bet plenty of men have daughters, mothers, sisters, and wives who, they would agree, shouldn't be held back."

Me, I’m torn between feeling thrilled to see women taking their seats on stage at a major cardiology meeting and being dispirited that, in 2017, this is even something that warrants writing about.

Even with a systematic, structured effort to switch up the faces at the front of the room, the wheels of change creak slowly forwards. In Europe, Poppas told me, Geneviève Derumeaux, MD (Louis Pradel University Hospital, Lyon, France), recently led a similar charge to change the balance of male and female faculty members to better reflect the 60/40 makeup of the ESC’s membership, but it turned out that women were more apt than men to turn down invitations.

This suggests, she said, that there are other hurdles to be overcome. Getting leave to attend may be harder for women, or they may have more trouble securing funding, Poppas observed. Moreover smaller meetings, where junior faculty—both male and female—might get the chance to cut their teeth as chairs or discussants before facing larger auditoriums, are surprisingly resistant to letting women take the stage, she added. “You’d be surprised by the things that are said. Things like, ‘Well, we need someone who has real expertise,’ the assumption being that a woman may have less expertise.”

Having more women, as well as other minority groups, get their start by presenting new data may be a key part of the puzzle. My tally suggests that the ACC has actually had fewer women presenting Big Tent trials than the other two major meetings.

“The two things are linked,” Poppas believes, pointing to National Institutes of Health research that looked at why women drop out of research fields. “If women aren’t given the opportunity to be PIs, or aren’t given the opportunity to present their data, it does become a vicious cycle that their names don’t get out there, or they don’t advocate to be the first author, etc.”

There are opportunities here for senior faculty to make a difference, she continued. “The same person doesn’t need to be the PI for 10 different studies. They can promote their junior faculty and as they [do so], they should think about all of their junior faculty: men, women, and people of color. More sharing and more mentoring is important.”

I’m also sensitive that gender is just one part of a larger diversity piece—it just happens to be the one that affects me, personally, the most. As a journalist writing about cardiology for 17 years, this has meant interviewing a lot of men. It’s also meant confronting some of the same stereotypes that no doubt face women cardiologists vying for a spot at the podium. In my time covering cardiology, I’ve been told I’d never be able to do the job of the male editor I replaced because I would be simply be “too nice.” Others have suggested I’ve attained certain roles because, as a woman, I’d be more malleable when the pressures of sales, advertisers, or CME programming were at odds with my news coverage decisions. One cardiologist publically praised one of my on-camera interviews by telling me he’d like to get me alone in a “broom closet.”

For these reasons and more, it was a pleasant surprise see so many women who’ve made time to speak with me over the years getting the opportunity to share their wise insights with a wider audience. And, in case you’ve read this far wondering when I’m going to recap some of the top stories from ACC 2017, let me give the last word to some of these women.

C. Noel Bairey Merz, MD (Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA), on FOURER: “The results are super positive. We’re all excited, and we will be now using this agent more. But let me set you up for some of the things we may be encountering: the results are very positive, but not for death reduction. So we are going to have to the Rita Redberg ‘less is more issue’ [come up] and be thinking about that. . . . Should we be paying a lot of money for drugs that don’t save lives?”

Pamela Morris, MD (Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, NC), on SURTAVI: “What I’m most struck by is the improvement at lower levels of risk and what the implications are for our younger more stable patients, who may prefer a nonsurgical approach, and we await that data.”

Dipti Itchhaporia, MD (Hoag Memorial Hospital Presbyterian, Newport Beach, CA), on the DEFINE-FLAIR and iFR-SWEDEHEART iFR/FFR studies: “I would say that there’s been a lot of discussion over the last several years over the appropriateness of performing PCI in stable coronary artery disease patients and . . . a real push to do some sort of physiologic assessment to really identify the appropriate patients to do those PCIs in. And I think FFR has been that standard. But we’ve noticed clinically that there’s been some reluctance to jump on the FFR bandwagon, and I think that the idea of a technology that can potentially be quicker and as safe as the established FFR is very enticing to a clinician.”

Roxana Mehran on ABSORB III: “Given what we have seen in ABSORB III 2-year data, showing clearly an inferior result on overall target lesion failure as well as an increase in target-vessel MI and stent thrombosis, even if you are . . .making important progress with avoiding small vessels and using proper sizing and predilatation and postdilatation. It’s important to note that in the current trial as we have it today, the majority of patients didn’t get the ‘PSP’ and the question that comes back to you, for the clinicians and for all of us, is: what do we do with the current patients who do have bioresorbable scaffolds? Should these patients remain on dual antiplatelet therapy for 3 years, until we know better?”

Find all of our comprehensive coverage of ACC 2017 on our conference page.

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full Bio

Comments