My Takeaways From ACC 2019: Breaking With Embargoes? Despite the Drama, Embargoes Set to Stay

It was a Reuters embargo breach that drove the most buzz at this year’s meeting. After 40 years of medical embargoes, is news still worth the wait?

Lasting impressions of the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2019 Scientific Session will be dominated, no doubt, by the low-risk TAVR trials—and not just the results, but also their unexpected early release.

Not that a range of interesting clinical trial results were lacking this year. TCTMD site stats suggest that readers were eager to learn about the two low-risk TAVR trials, but also the AUGUSTUS trial of triple versus dual therapy in A-fib patients with ACS or undergoing PCI, two studies dropping long-term aspirin in dual antiplatelet therapy, SAFARI comparing radial and femoral PCI in STEMI, COACT testing an early intervention strategy in cardiac arrest, and the new primary prevention guidelines, among others.

But a broken news embargo generates a different flavor of interest, such that news of the “break” itself sometimes eclipses, sometimes boosts, the actual results of the study.

When word went around that Reuters had published a story on the low-risk TAVR results a day ahead of schedule, there was a palpable sense of deflation in the newsroom, both among the ACC staff and the reporters beavering away at their stories. Most of the print news outlets on-site at ACC this year—TCTMD included—were already working hard on this story, had interviews scheduled or transcribed, and had rough drafts written, most of us trying to pull together a story that had the details, nuance, and commentary required to get the story “right.” An embargo breach prompts deep sighs and some decision-making: run with what you have? Or continue as you were, gradually pulling together the polished, multifaceted story to go live at the time of the presentation the following day?

For me, the editor at an online-only news site, this decision was easy. I figured that for a physician audience, even a bare-bones TCTMD story would be better than what Reuters had flapping in the wind. If physicians were trying to get details and insights, I wanted them to find them on TCTMD. We got reporter Michael O’Riordan’s story live within an hour of the embargo lift and swiftly updated it using rushed interviews with key investigators and comments from outside experts. Then we continued to update our story after seeing the main tent presentation and discussion the next day, followed by the official press conference—neither of which had been rescheduled to take place the day of the break.

Do most people read the different iterations of a story like this, checking back for updates (as we suggested at the end of our initial story)? I doubt it. But ultimately our full, final story remains online for anyone searching the web in the days, weeks, and months ahead.

What Went Down

So how did this embargo break happen? I had several people reach out and ask me this during the ACC meeting, amid swirling theories as to why and how the story had been released. The New England Journal of Medicine asked Reuters for answers and got a response from Heather Carpenter, Senior Director of Communications. She said that the news outlet had “inadvertently released embargoed information” and that they had “reviewed our internal processes and taken steps to ensure that we don’t repeat this mistake.” Also: “We regret our error.”

The NEJM has elected not to sanction Reuters. “We decided that because the Reuters’ embargo break was not intentional—they were the first to contact us about the break—ultimately no good would be served by temporarily stopping their embargoed access and silencing their coverage,” a NEJM media spokesperson told TCTMD. “We are all in the same business of sharing high-quality information, and we believe in the value of the embargo to allow news organizations to prepare comprehensive news coverage. Sanctions would not help this aim.”

The ACC has taken a different tack. Reporters and/or editors from Reuters will not be authorized to register as on-site media for next year’s meeting, scheduled to take place in Chicago from March 28 to 30, nor will they be able to access embargoed materials in advance of that meeting.

Why Embargoes Were Created

As MIT biologist, journal editor, and founder of the Center for Science Communication at Vanderbilt University, Vivian Siegel, PhD, wrote in a blog post explaining the history and rationale for embargoes in science and medicine, the concept was first introduced with the dual aim of meeting “a scientific journal’s desire to protect its own newsworthiness and to protect the public from misinformation.”

Indeed, all of the medical journals we cover on TCTMD, as well as the meetings we attend, insist that reporters adhere to strict embargo policies that allow us to access research results a few days (or hours) in advance of publication or presentation, as long as we promise not to make those public. The idea is that we reporters will have time to bend our minds around difficult data, interview study investigators, and also—ideally—seek out knowledgeable experts who can comment on those results for our stories. The race to “scoop” other news outlets is also minimized for these types of stories.

And, for the most part, we obediently adhere to these rules rather than risk the repercussions: losing access to a meeting or journal for some punitive period of time. I myself, along with a colleague at theheart.org, got booted from the European Society of Cardiology Congress in 2012 when an affiliate publication—not our own—accidentally scheduled an embargoed story to go live hours ahead of the embargo. The 1-year ban imposed was subsequently relaxed when we successfully petitioned to explain that we hadn’t been responsible.

Sponsors of trials that have access to data and analyses are also required to keep mum. Researchers, too, are supposed to adhere by these rules: if they receive a paper by a reporter to review ahead of an interview, the idea is that they’ll keep it to themselves. If asked to review a paper for a journal, the reviewer must keep any information gleaned confidential. Martin Leon, MD (NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia University Irving Medical Center, New York, NY), one of the primary investigators for PARTNER 3, was on the receiving end of these rules back in 2007, when he was sanctioned by the NEJM and the ACC for releasing details from the COURAGE trial results ahead of the trial’s presentation and publication. Leon himself was a reviewer, not an investigator, and to this day he believes that his comments at an investors’ meeting did not constitute an embargo breach. Fast forward 12 years and it was Leon himself learning that his own trial had been prematurely released, which he said he and others took hard.

“Everyone was deflated,” Leon told TCTMD. “All the effort that went into building to a crescendo, that would really be based on exposing the data for the first time that morning: now the wind was out of our sails. We felt very deflated and I think we got our selves back up emotionally, but we didn't know if that room was going to be filled or empty, if people were going to be responsive or bored.”

Broken News?

An overview of the past, present, and future roles of news embargoes by Sonja Gruber, an editor at Austrian Press Agency in Vienna, argues in a blog (ironically) for the Reuters Institute that embargoes have been a core part of the media policies of major science journals since the 1920s and are likely to remain intact for years to come, even as they’d started to decline in other fields, including business and entertainment news.

Today’s vastly accelerated news cycle, with the advent of simultaneous online publications and the fact that more and more people digest the news from mobile devices, not print platforms, puts new pressures not only on how news is timed but also on how it is disseminated. There’s also the problem of media conglomerates, where multiple outlets are owned by massive single entities, which might share back-end technology across their global distribution. More than 40 years after embargoes were first proposed for medical and science news, are they working the way they should?

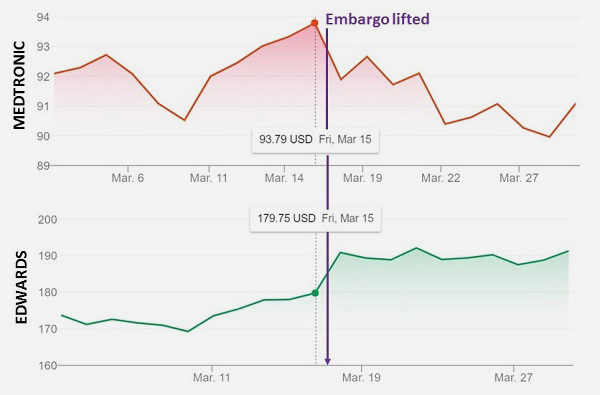

I’m not so sure. Plenty of times, when I reach out to someone I’ve selected to comment on a study for my story, they’ve already seen the embargoed results—and not always because another journalist has been in touch. A quick look at the stock price for the two devices studied in the low-risk TAVR trials hints that despite what sounds like extraordinarily strict access to the final results, word was already circulating of positive outcomes the week prior to their weekend release. Edwards Lifesciences’ stock continued to rise the week following the ACC meeting, whereas Medtronic’s rose all week, then appeared to decline after the weekend release. Recall: PARTNER 3 showed superiority for the Sapien 3 device over surgery for the primary endpoint of death, stroke, and rehospitalization at 1 year, whereas the Evolut Low-Risk Trial showed noninferiority, but not superiority, for the Evolut devices versus surgery for what some called a “harder” endpoint of death or disabling stroke at 24 months.

Jeffrey J. Popma, MD (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA), co-principal investigator for the Evolut Low-Risk Trial, said he is deadly serious about embargoes.

“As an investigator for this and other trials, I hold the final manuscript in complete confidence and don't even share it with my partners until it has been formally released,” Popma told TCTMD in an email. “This is primarily to make certain that I am not the one who inadvertently releases the data—because . . . it does happen, and the mistakes are often innocent by those who are not familiar with the topic or the process. For this one, I would not send the manuscript to my own institution’s communications department for fear of an innocent but premature release; however, my press office did receive a pre-release copy from the NEJM a day or two before Sunday's embargo. But it didn't come from me!”

I really do think that we are entering a phase where the exposure of new data to so many groups of people will make embargo breaches—both intentional and unintentional—inevitable. Martin Leon

Leon, likewise, said he’d never been through such a rigorous process for protecting the embargo as he did for PARTNER 3. He said it was “beyond anything I've ever seen before,” and included signing a legal document, with penalties to the individual regardless of whether an embargo breach happened intentionally or unintentionally. In fact, the investigators and sponsor actually pushed back to the ACC, Leon said, when the meeting planners requested access to the trial results much earlier than the investigators and sponsor believed necessary.

An unintentional side effect of the embargo break was investigators had the chance to test one of the stated reasons for having an embargo in the first place—namely, whether interactions with reporters both under embargo, then after embargo, were any different, or led to different quality stories. And did Leon notice any differences, asked TCTMD?

“Absolutely not,” Leon replied. “I really do think that we are entering a phase where the exposure of new data to so many groups of people will make embargo breaches—both intentional and unintentional—inevitable.” Simultaneous publications, he added, “are major responsible factors that contribute to these sporadic embargo breaches, which I think are going to be unavoidable if we're faced with exposure of the data to large news media outlets days before it's actually presented or available online.”

Leon continued “I really do believe that it would be of value to have the various stakeholders [including] the high-tiered journals—this is the Lancet and the NEJM, JAMA, and probably JACC and Circulation—somehow agree on a policy that reduces the exposure risk to embargo breaches.”

TCTMD put the question to the ACC and the NEJM: are embargoes still worth the effort and risk or is it time to consider changes? The ACC tapped their CEO Timothy W. Attebery, DSc, MBA, FACHE, who emailed the following response:

“The ACC strongly believes in medical news embargoes and never questioned their value. By placing embargoes on research at our Annual Scientific Session and on articles in our journals, we are providing researchers with the opportunity to be first to present their research, while at the same time giving journalists an opportunity to prepare informed news articles that can be released simultaneously. Both avenues of data dissemination hold tremendous value and the system works well when respected by all parties involved.”

A NEJM spokesperson, responding by email, said: “It is impossible to know what we will do in the future because every situation is different. We evaluate every situation with great care and talk with as many involved as possible.”

Popma told TCTMD that, if given a say in the matter, he’d rather the NEJM and other journals released their manuscripts to the media at the same time as publication, “with no early releases,” thereby leveling the playing field.

“Mistakes happen,” he said. “I suspect this one was innocent, but if the NEJM manuscripts are being emailed around ahead of time, it is very hard to ensure confidentiality or to prevent an embargo break. It is human nature.”

Shelley Wood was the Editor-in-Chief of TCTMD and the Editorial Director at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (CRF) from October 2015…

Read Full Bio

Comments