Surgery After Failed Mitral Edge-to-Edge Repair Tends to Be Replacement

Repair is often off the table, and that information should be part of the informed-consent process for TEER, experts say.

When surgery is needed to correct residual or recurrent mitral regurgitation (MR) after transcatheter edge-to-edge repair (TEER), chances are that the patient will need to have the valve replaced rather than repaired, shows a study using the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) Adult Cardiac Surgery Database.

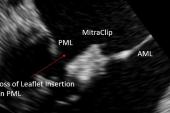

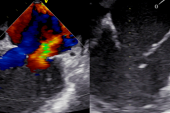

Of patients who had mitral surgery after TEER—nearly all of which would have been done with the MitraClip (Abbott) during the study period—only 4.8% underwent surgical repair rather than replacement, Joanna Chikwe, MD (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA), reported during the virtual American Association for Thoracic Surgery 2021 meeting over the weekend.

Prior to this study, there were no robust, country-level data on how patients fare if TEER fails to provide a durable reduction in MR and surgery is required, Chikwe told TCTMD. “It was, I think, a surprise to everybody how a failed MitraClip takes a surgical repair off the table and 95% of these patients end up with a mitral valve replacement.”

That’s important “because as we start expanding the indications for MitraClip to lower-risk and younger patients, it’s essential that when those patients are consented, they understand that failure of a MitraClip is by and large consigning them to a mitral valve replacement. The valve’s not surgically repairable after that,” she said, noting that a replacement is not as durable as a repair.

Cardiothoracic surgeon Thomas Gleason, MD (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), a member of the STS board of directors, agreed that patients need to be made aware of this. He explained that it’s tricky to perform a surgical repair after TEER because removing the clip causes so much damage. “What you’re left with after it’s taken out is often an unrepairable valve due a destroyed leaflet upon removal of the MitraClip and/or intense fibrosis of the leaflet formed in response to the MitraClip—both precluding a durably repairable valve,” he commented to TCTMD.

Better Outcomes at More-Experienced Centers

Chikwe noted that there have been about 15,000 TEER procedures performed in the United States since 2014, with moderate or severe MR observed in about 20% of patients within a year of the intervention. A minority of these patients are referred for surgery, and the outcomes in this group are not well understood.

For the current study, published simultaneously online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, the investigators examined data on 463 patients (median age 76 years; 49.0% women) who underwent primary mitral valve surgery after TEER between June 2014 and June 2020. Of these, 177 had underlying degenerative pathology and the rest did not. Most patients underwent concomitant procedures, most frequently closure of an atrial septal defect (39.9%), closure of the left atrial appendage (35.0%), and tricuspid repair (30.0%).

Overall, this was a high-risk group, with a median STS PROM score of 7.6% (7.3% in the degenerative subset and 7.6% in the other patients). That’s reflected in the relatively high rate of operative mortality (10.6%), encompassing deaths that occurred in the hospital or within 30 days of follow-up.

Patients with degenerative disease had a lower mortality rate than did the rest of the cohort (6.3% vs 13.3%; P = 0.02), and if urgent and emergent procedures were excluded, the rate was just 2.8% in the degenerative group. That’s “pretty respectable given the high-risk nature of this cohort,” Chikwe said.

There was a strong inverse association between hospital surgical volume and operative mortality, such that centers performing more than 10 such operations achieved a mortality rate of just 2.6% and those performing fewer had rates of 10.4% to 16.8% (P = 0.04). “I suspect that it really does just highlight the ability of higher-volume centers to safely manage all of the comorbidities associated with high-risk patients more effectively,” Chikwe said.

She acknowledged some study limitations stemming from the use of registry data, as well as the lack of information on the interval between TEER and surgery and on key anatomic and procedural characteristics.

Nonetheless, she concluded during her presentation, the results should “inform patient consent for transcatheter edge-to-edge repair, clinical trial design, and clinical performance measures.”

A High-Risk Group?

Gleason said the low mortality rate observed in the most-experienced centers and among elective patients with degenerative etiology raises questions about whether some of the patients in this study were really high-risk.

“One should pause to consider that those patients with degenerative mitral disease who at the time of MitraClip placement were considered high risk but then went on after failed clip to undergo mitral replacement with a fairly low mortality risk should probably have been considered low to moderate risk for surgery originally, and surgery should have been considered, reducing the likelihood for reintervention,” he said.

Commenting for TCTMD, interventional cardiologist Adnan Chhatriwalla, MD (Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, MO), made the case that the patients included in this study were indeed high-risk. He said one could surmise that patients whose TEER procedure fails likely have more-complex anatomy that would not have been amenable to surgical repair in the first place.

One piece of information this study does not provide is what proportion of patients undergoing TEER will later require surgery, but “back-of-the-envelope” estimates can provide some indications, he pointed out. A prior study from his group showed that about 15,000 MitraClip procedures were performed between November 2013 and March 2018, and the current study included about 500 patients who had surgery after TEER. That suggests about 3.5% of patients undergoing TEER will later require an operation to address MR, “which is low, and I think that that’s a positive,” Chhatriwalla said. “It shows that the vast majority of patients who undergo these transcatheter procedures do not require surgery.”

He noted that COAPT and EVEREST showed that 10% to 15% of patients had grade 3+/4+ MR—and might be considered for surgery—after the MitraClip procedure. If only roughly 3.5% actually underwent surgery, as suggested by the current study, it means only about one-quarter of patients without a successful TEER result go to surgery and the remaining three-quarters don’t, “presumably because they really were high-risk or prohibitive-risk candidates that even though the transcatheter procedure failed, they’re not eligible for surgery,” Chhatriwalla said.

TEER Likely to Improve Over Time

Still, patients considering their options—TEER or surgery—should be informed that if they go for the transcatheter approach and later need surgery, it will likely be a replacement rather than a repair, Chikwe said. “Younger and lower-risk patients with primary degenerative mitral valve regurgitation should be very aware that in the event that their MitraClip is not successful in the long term, they’re essentially consigning themselves to mitral valve replacement, and that has to be embedded in the consent that we give to patients both in clinical practice and in clinical trials.”

She said she’d be surprised if it was part of the consent process now because this information wasn’t available. “I think there’s a lot of optimism in the cardiology community that these valves can be repaired if the MitraClips fail, and this very, very conclusively shows that in the vast majority of patients that simply isn’t the case,” Chikwe said. “MitraClips essentially destroy everything that you need to effect a competent and durable surgical repair. . . . It can be done, but it’s not usually a durable option for patients.”

Chhatriwalla agreed that it’s reasonable to include this information in the consent process, although TEER is supposed to be confined to high-risk and prohibitive-risk patients who would not be good candidates for surgery at this point. “It’s much more pertinent if we’re going to translate this technology into lower-risk patients who are going to be better surgical candidates,” he added.

One thing to consider, however, is that TEER technology is improving over time, Chhatriwalla said. “Looking at this retrospective time frame is valuable, but it’s also possible that with newer-generation MitraClip devices and with other devices like Pascal [Edwards Lifesciences] to perform edge-to-edge repair, the procedural success rates will be higher, the long-term results may be better, and maybe the number of patients who require a surgery down the road will be fewer. The environment is always changing,” he said. What won’t likely change, he added, is that when surgery is required, it’ll likely be a replacement.

From Gleason’s perspective, “patients and clinicians need to be aware that the less-invasive MitraClip procedure, while it sounds like a straightforward procedure relative to surgery, can have dramatic implications in these higher-risk patients both with respect to rendering a markedly diminished chance of subsequent valve repair on the one hand, and on the other, if subsequent surgery is required, rendering a higher risk with secondary surgery than if surgery had been performed primarily.”

Todd Neale is the Associate News Editor for TCTMD and a Senior Medical Journalist. He got his start in journalism at …

Read Full BioSources

Chikwe J, O’Gara P, Fremes S, et al. Mitral surgery after transcatheter edge-to-edge repair: Society of Thoracic Surgeons database analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Chikwe reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Chhatriwalla reports serving on the speakers bureau for Abbott Vascular and serving on the speakers bureau and being a proctor for Edwards Lifesciences.

Comments